Informal settlements in Colombia: A look at the city of Tunja (2010-2022)

Asentamientos informales en Colombia: una mirada a la ciudad de Tunja (2010-2022)

Sara Manuela Simijaca Salcedo*

Johanna Inés Cárdenas Pinzón**

Héctor Javier Fuentes López***

* Especialista en Planeación y Gestion del Desarrollo Territorial. Universidad Pedagógica y Tecnológica de Colombia. Tunja, Colombia, sara.simijaca@uptc.edu.co © https://orcid.org/0009-0004-0202-3449

** Magíster en Economía. Docente de la Escuela de Economía de la Universidad Pedagógica y Tecnológica de Colombia. Tunja, Colombia, johanna.cardenas@uptc.edu.co © https://orcid.org/0000-0002-4471-0931

*** Estudiante Doctorado en Estudios Sociales. Magíster en Ciencias Económicas. Docente titular Universidadm Distrital Francisco José de Caldas. Bogotá, Colombia, hjfuentesl@udistrital.edu.co © https://orcid.org/0000-0001-6899-4564

How to Cite: Simijaca Salcedo, S. M., Cárdenas Pinzón, J. I., & Fuentes López, H. J. (2024). Informal settlements in Colombia: A look at the city of Tunja. Apuntes del Cenes, 43(78). Págs. 235-264. https://doi.org/10.19053/uptc.01203053.v43.n78.2024.17288

Reception date: March 2nd, 2024 Approval date: June 18th, 2024

Abstract:

This paper presents a comprehensive analysis of informal settlements in Tunja, Colombia, from 2010 to 2022. It examines the historical, social, and economic factors that contribute to these settlements, using various data sources, including development and territorial planning plans, the Agustín Codazzi Geographic Institute, and local government records. The study highlights significant inequalities in access to public services between urban and rural areas, exacerbated by environmental hazards from nearby mines, landfills, and sewage treatment plants.

The research employs a descriptive and explanatory approach, detailing the historical context and theoretical frameworks related to agglomeration economics, territorial inequality, and urbanization processes. A historical-deductive method ensures logical consistency in the analysis of data from 2010 to 2022. The study also utilizes georeferencing techniques to present spatial data on service coverage and demographic characteristics, differentiating urban and rural disparities.

Findings show that informal settlements in Tunja are predominantly located on the periphery of the city, with significant disparities in service coverage. While urban areas have over 90% coverage of basic services, rural areas lack adequate infrastructure, particularly sewage, gas, and internet services. The study identifies specific settlements, such as Runta and Pirgua, details their access to services and highlights environmental and structural issues.

Keywords: inequality, settlements, city, rural area, public service, Colombia.

JEL classification: I38, O18, R11, R21, R23.

Resumen:

Este artículo presenta un análisis integral de los asentamientos informales en la ciudad de Tunja, Colombia, desde 2010 hasta 2022. Explora factores históricos, sociales y económicos que contribuyen a estos asentamientos, utilizando una variedad de fuentes de datos, que incluyen planes de desarrollo y ordenamiento territorial, el Instituto Geográfico Agustín Codazzi y registros del gobierno local. El estudio destaca desigualdades significativas en el acceso a servicios públicos entre áreas urbanas y rurales, exacerbadas por peligros ambientales de la minería cercana, vertederos y plantas de tratamiento de aguas residuales. La investigación emplea un enfoque descriptivo y explicativo, que detalla el contexto histórico y los marcos teóricos relacionados con la economía de aglomeración, la desigualdad territorial y los procesos de urbanización. Un método histórico-deductivo asegura la coherencia lógica en el análisis de los datos de 2010 a 2022. El estudio también utiliza técnicas de georreferenciación para presentar datos espaciales sobre la cobertura de servicios y características demográficas, diferenciando las disparidades entre lo urbano y lo rural. Los hallazgos revelan que los asentamientos informales en Tunja están predominantemente ubicados en la periferia de la ciudad, con disparidades significativas en la cobertura de servicios. Mientras que las áreas urbanas muestran una cobertura superior al 90 % para los servicios básicos, las áreas rurales carecen de infraestructura adecuada, especialmente en servicios de alcantarillado, gas e internet. El estudio identifica asentamientos específicos como Runta y Pirgua, puntualiza su acceso a servicios y destaca problemas ambientales y estructurales.

Palabras clave: desigualdad, asentamientos, ciudad, zona rural, servicios públicos, Colombia.

INTRODUCTION

The Colombian Constitution recognizes that all Colombians have the right to adequate housing, and that, in addition, this right must be fulfilled through government policies such as housing programs and plans (Constitución Política de Colombia, 1991, art.51) that guarantee this right to its citizens. According to the Constitutional Court, the condition of adequate housing is determined by the elements of dignity and security, therefore, the existence of informal settlements requires government intervention in accordance with the provisions of the Constitution. For UN-Habitat (2018), informal settlements are poor neighborhoods or slums that are in situations of overcrowding and illegality because those who inhabit these territories do not have any legal right over them, that is, they do not have this right. Likewise, land is the refuge of people in poverty who do not have access to decent housing and influence the development of a country by affecting the quality of life of the people who live there (Wekesa et al., 2011).

In Colombia, urban development has brought with it not only their modernization but also the growth of marginal neighborhoods, which were mostly located in areas of environmental risk (Uribe, 2011). In Tunja, Municipal Agreement No. 0014 of 2001 (Concejo Municipal de Tunja, 2001) recognizes the existence of houses on risky land and illegal urban development processes, especially in the existing gullies for that year. The presence of informal settlements reflects gaps in territorial planning, since an informal settlement is not only due to the illegality of the land but also to the lack of basic services. In addition, some of these settlements are located in environmentally hazardous areas which increases the risk faced by the population living in these areas.

The objective of this document is twofold: firstly, to indicate the main historical aspects associated with the existence of informal settlements in Colombia; secondly, to contextualize the socioeconomic conditions of the informal settlements of Tunja, with a view to contributing to the process of recognition of these territories, especially in the rural area, given the evident low quality of life and the dangers faced by its population on a daily basis.

This work is divided into the following sections: the first comprises the introduction, the second a conceptual description related to space as an object of study and territorial inequality is made, the third the applied methodology, the next includes historical aspects of Colombia related to the existence of informal settlements, the fifth details the population, habitation and demographic characteristics of the city of Tunja, and finally the conclusions are related.

THEORETICAL CONCEPTUAL REVIEW

Space as an Object of Study

In examining the concept of space according to Polèse and Rubiera (2009) from an economic perspective, it becomes evident that the notion of space can be understood through the lens of related concepts such as territory, environment, region, and country. Furthermore, the concept of space can be understood from a social perspective, with theoretical, geometric, or mathematical notions being referenced. Nevertheless, in the analysis of these authors, the term "geographical space" stands out, which refers to lived, real, or terrestrial space. In other words, the concept of space can be understood in a variety of ways, depending on the context in which it is being discussed. Consequently, defining it with precision can be challenging, as it may be associated with a range of similar terms, depending on the object of study or the environment in question.

Similarly, for Andion et al. (2009) the concept of space seen from the perspective of economic development takes the notion of territory, which cannot be seen as a static concept limited by geographical or administrative terms, on the contrary, it is a concept that varies according to the case analyzed. That is, space can take on different forms depending on the context, region or reality to which it belongs. Moreover, they affirm that this concept became relevant after the Second World War due to the territorial imbalances caused, which motivated economists and geographers to take an interest in this field of study.

The inclusion of the spatial dimension in economics is discussed by Isard (1949) by criticizing of authors such as Hicks, Mosak, Lange and Samuelson, who exclude space as an object of study. On the contrary, Isard sees in the spatial economics as a theory that understands economics as a whole. The first generation of authors on location theories were Von Thunen, Christaller and Zipt, who each developed their models and contributed to the foundations of spatial economics (Haggett et al., 1967). In 1826 the work of the economist Von Thünen was published, where he developed a spatial economic model based on rural development, this model divided economic and agricultural activities according to the economic performance of each one (Sasaki & Box, 2003).

Furthermore, the significance of geography within the spatial economy is acknowledged (Buzai & Baxendale, 2010). Geography is defined as the scientific study of territorial planning, encompassing methodologies, knowledge, and tools such as statistics, geographic information systems, cartography, and others. As posited by Bonet (2007), economic geography, as an area of economic theory, only began to gain relevance in recent years. This field of study concerns the analysis of the geographical distribution of economic and social activities. In other words, it seeks to understand the factors that influence the concentration of economic and social activities in specific locations within a territory.

In 1999, the term New Economic Geography, proposed by Masahisa Fujita, Paul Krugman and Anthony Venables, was introduced to the academic community to underscore the contributions made to regional economies since the 1990s (Trívez, 2004). In their commentary, Fujita and Krugman (2004) address the following:

The issue to highlight in the new economic geography is that it tries to provide some explanation for the formation of a great diversity of forms of economic agglomeration (or concentration) in geographical spaces. The agglomeration or clustering of economic activity takes place at different geographic levels and has a variety of different forms. Taking an example, a certain type of agglomeration arises with the grouping of small shops and restaurants in a neighborhood. We find another type of agglomerations in the process of formation of cities, where they all acquire different sizes, (…) in the emergence of a variety of industrial districts; or in the existence of strong regional inequalities within a country. (p. 179)

In other words, taking into account the agglomeration of economic elements, phenomena such as the formation of cities, the unequal distribution of wealth, the concentration of poverty, among others, can be explained. Polèse and Rubiera (2009) highlight the importance of the historical processes of cities and countries in the study of space, since they allow comparative analyzes through the processes of industrialization, development and urbanization which affect consumption structures, wealth distribution of, employment opportunities, market systems and planning.

Territorial Inequality and Territorial Settlements

According to ECLAC (2016), inequality explains that the structuring axes of inequalities are related to inequality of income, means, gender, access to productive means, ethnic-racial and territorial. Territorial inequality is understood as the difference in the distribution of resources, which have a surplus and excessive spending in rich countries or territories, as opposed to poor countries or territories, where these resources have a significant deficit (George, 1983), that is, territorial inequality is related to the level of development of countries and their management of resources.

However, this structuring axis is also manifested through access to services such as health, education, quality infrastructure, drinking water equipment, sanitation and transportation. Similarly, it is manifested through social, physical, and symbolic relationships and cultural aspects that exist with the territory. This relationship can reinforce positive or discriminatory facets with the place of origin or residence (ECLAC, 2021).

According to Cazzuffi (2017), Territorial inequalities particularly affect people living in the poorest areas, impacting on aspects such as access to quality employment, education and health. Moreover, differences in climatic, security, and demographic conditions, among others, imply sectoral gaps within the same territory (neighborhood, city, department, country). For this reason, the territory is part of the structural study of inequality, because its conditions influence the social development of people who live in the most backward spaces (Czytajlo, 2017).

In Latin America, the urban areas of the cities are those that concentrate the economic, political and administrative power due to rapid urbanization that did not have prior planning, consequently, the cities of Latin America present high levels of inequality, environmental degradation and weak economies (ECLAC, 2017 2021). In fact, the case of Colombia shows that one of the factors that increases in inequality is land ownership due to its unequal distribution (Cárdenas & Vallejo, 2016).

The dictionary of the Royal Spanish Academy defines settlements as uninhabited areas, places or facilities that are occupied by displaced persons or migrants. The cause of informality can be attributed to factors such as low income levels, unrealistic urban planning, few plots of land with access to public services and a dysfunctional legal system. Likewise, the consequences of this informality are reflected in the high costs to those who live in these settlements, the lack of public services, social segregation, environmental and health hazards, and inequitable civil rights (Fernandes, 2011).

The term "informal settlements" is recognized with different names in various countries or territories, as documented by Davis (2006) and Romero (2019). These include favelas in Brazil, slums in Buenos Aires, lost cities in Mexico City, communes in Colombia, callampa towns or shanty camps in Chile, and pigeon marshesin Montevideo, among others. In this regard, Vázquez (2019) assures that the informality of the settlements generates problems in the quality of life of the inhabitants due to the difficulty of bringing basic services and decent housing to illegal areas or outside the urban planning regulations. In other words, living in an informal settlement implies not only difficult access to public services, but also zero access to urban infrastructure, telecommunications, and the condition of invisibility that these residents face due to exclusion. social due to its informality (Techo Latam, 2021).

In Colombia, as stipulated by Law 2044 of 2020, settlements can be classified as either consolidated illegal human settlements or precarious illegal human settlements. This classification is based on the condition of the housing in terms of materials, access to services, and level of development. It should be noted that the term "illegal consolidated" is used to describe settlements that, despite being located in an unauthorized area, have reached a relatively advanced level of development. This is evidenced by the presence of consolidated housing with stable materials and access to paved roads. In contrast, the second category encompasses settlements that lack both consolidated and developed urban planning. Nevertheless, both categories are characterized by an unplanned, unauthorized, and illicit location of these residences (Law 2044 of 2020).

METHODOLOGY

To characterize the informal settlements in Tunja, the descriptive method is used since it begins by detailing the historical context and theoretical concepts related to the agglomeration economy, territorial inequality and urbanization processes. Likewise, the type of explanatory study is used to respond to the causes of the phenomenon studied, in this case, the informal settlements in Tunja.

The selected period is from the year 2010 to the year 2022, which was chosen based on the data and available bibliography. Likewise, the historical-deductive method is used to achieve logical consistency through the search and obtain data on informal settlements in Colombia and mainly in Tunja. For this purpose, sources of information such as municipal and national development plans and territorial planning plans, the Geographic Institute Agustín Codazzi, and academic production related to the research topic are taken into account. The above sources will be key not only for the characterization of the settlements but also for the city of Tunja and its socio-economic conditions, which is why it is intended to identify the conditions of housing and access to public housing services.

Additionally, a georeferencing methodology based on the 2021 data from the Tunja Mayor's Office is applied to the ArcGIS tool from which spatial data from providers such as Tomtom, Garmin, Fourquare and METI/NASA are also integrated to present the data in geospatial form and to include layers that allow the insertion of roads, routes, and other data in satellite form.

Therefore, the socio-economic representation of the urban area of Tunja is made through the application of georeferencing systems that allow differentiating the coverage of basic services and the educational level of the inhabitants according to the neighborhood in which they live. To observe this difference, the layer of neighborhoods in the urban area of Tunja was used with a total of 158 polygons representing each of the neighborhoods. With this methodology, the disparity between neighborhoods is known and therefore additional results can be obtained not only on the inequality between the rural and urban areas of the municipality but also on the disparity between the areas of the capital. The interpretation of the spatialized data is obtained by identifying the tone assigned to each level of service coverage in order to know the proportion of properties according to each neighborhood that do or do not have services such as water and electricity.

THE EXISTENCE OF INFORMAL SETTLEMENTS IN COLOMBIA

Regarding the history of Colombia, there are elements that have marked the country's memory, among them: drug trafficking and the birth of guerrillas, these two factors, according to Unidad de Paz (2000), these elements have caused situations of increased violence, increase in armed conflict, weakening of public institutions, and corruption. Also, one of the problems that characterizes Colombia is forced displacement and land appropriation.

According to the Unidad para las Víctimas (2023), among the events or conflicts that affect the Colombian population are: forced displacement, forced disappearance, abandonment or forced dispossession of land, threat, terrorist act, attacks, antipersonnel mine, kidnapping and homicide, with Bogotá and Medellín being the cities with the greatest reception of displaced population (Londoño Toro, 2004), likewise, Pérez and Córdoba (2019) say that the displaced population is accentuated in residual spaces on the periphery of the cities, creating an "informal invasion."

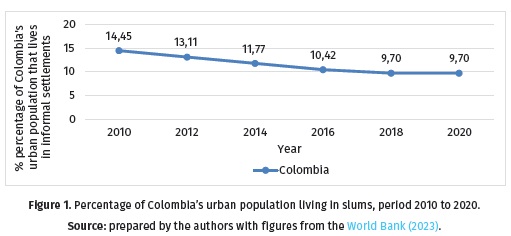

That is, displacement is a cause of the emergence of informal settlements in Colombia, since it forces people, families and communities to locate in new cities, places and territories, therefore, forced displacement would act in this case as a sociodemographic phenomenon. that influences the urbanization and growth of cities (Gómez, 2010), such as Bogotá and Medellín. Figure 1 shows the percentage of Colombia's urban population living in informal settlements also known as slums.

By 2016, Bogotá had 125 informal settlements located in the periphery, where the presence of a population displaced by the armed conflict is recognized (Techo Colombia, 2016). In the case of Medellín, it is clear that it not only presents the condition of receiving of displaced people who settle in its territory, if not also, the expulsion of the population due to violence (Gómez, 2010).

The figures (2 and 3) below refer to the most urgent needs and the main problems of informal settlements in Bogotá for the year 2015, which reflects that the inhabitants of these settlements must not only face their condition of displacement by violence, but also areas of social conflicts such as drug trafficking and theft, in addition to limitations in security and access to basic services.

Among the Colombian cities with experience of intervention in settlements is Medellín, where in 1999, with the first Territorial Planning Plan, instruments such as Urban Regularization and Legalization Plans were used, which did not meet expectations since it was found that processes were clearly generated for the legalization of property, without benefiting the informal settlements, since there was no improvement of roads or provision of social and community facilities; on the contrary, it was a process that favored only the administration, as with the legalization of properties, higher taxes had to be paid (Velásquez-Castañeda, 2013).

In 2004, however, the Integral Urban Projects arrived in Medellín with the aim of planning and intervening in marginalized, segregated areas, and affected by poverty and violence.

This strategy has led to processes of neighborhood consolidation where communes have been equipped with parks, streets and pedestrian bridges that connected neighborhoods and communities that had been divided by violence; access to primary and secondary education has also been improved, and cultural and sports projects, among others, have been supported (Echeverri & Orsini, 2010).

On the other hand, the concept of settlement in the case of Tunja is evoked for the pre-Columbian and conquest era, where the presence of indigenous communities is recognized. These communities were located in the Cundiboyacense highlands where they were favored by the water bodies, mountains and hills of the region (Portilla Tarazona, 2021). As Francis (2002) indicates, the time of the conquest had a serious impact to these settlements, as the population went from around 230,000 indigenous people at the beginning of the conquest to 47,554 in the 17th century, and 25,000 in the 18th century.

Likewise, the conquest of America brought with it diseases such as smallpox, measles, influenza, bubonic plague, yellow fever and cholera, which also affected the indigenous population, who had no immunity to these evils. The impact of these diseases was such that smallpox is associated with the birth of an informal settlement in the San Lázaro neighborhood of Tunja, since it was a sector far from the capital where they could leave the sick and, failing that, reject them (Hidalgo, 2012a).

DEMOGRAPHIC, GEOGRAPHIC, AND HABITATION CHARACTERISTICS OF THE CITY OF TUNJA

The demographic dynamics of the city reflect some changes in the last 13 years, given that there is a preference of the population toward the urban area of the city, which has been increasing in the last 23 years, however, this growth in the capital is contrary to the crude birth rate due to a drop in the number of births starting in 2015, leaving a natural growth rate with a negative slope.

However, the population growth in the capital of Tunja is the result of the migratory growth rate where, starting in 2014, an increase in said population is reflected, reaching its peak in 2019, with the results of the following three years being uncertain without the consequences of the COVID-19 pandemic.

According to data from DANE (2018), in Tunja for the year 2018, the largest number of migrants from municipalities in Colombia came from Duitama, Sogamoso, Bucaramanga, Bogotá, Medellín, Barranquilla, among others; likewise, the largest number of migrants from another country were of Venezuelan, Ecuadorian, American and Spanish origin. However, although one of the causes of the existence of informal settlements in Colombia is forced displacement, there is no record of the place of residence of these migrants, nor of the place of birth of the people who have settled in these spaces.

Hidalgo (2012b) points out that since 1907, marginal type constructions have been recorded in the city, which are part of the informal constructions that spread throughout the 20th century until 2005 (Appendix 1), these marginal type constructions appeard in different areas of the city, mainly in the neighborhoods of San Lázaro, Libertador, Patriotas, Triunfo, Milagro, Altamira, Dorado, Asís, La Granja, Gaitán, Carmen, Nazaret and Santa Lucía, which belong to the urban area. In this regard, the land occupation in Tunja is significant for the type of informal urban structure; however, Hidalgo (2012a) recognizes informal housing as housing that has not been planned in advance, but is also housing in precarious conditions.

On the other hand, the Town Hall of Tunja (Alcaldía Mayor de Tunja, 2021) establishes that the percentage of illegal neighborhoods in the city makes up more than 90% of the land; however, this percentage is determined by the legal conditions under which the neighborhoods were built but not by their socioeconomic conditions or by compliance or non-compliance with urban planning regulations.

Regarding the coverage of service in Tunja, Table 2 shows that in 2005 more than 50% of the city had all basic services, although there were only 18 legalized neighborhoods, i.e., their informal status did not affect the provision of basic services which shows that despite being an illegal city, not all of its neighborhoods are marginalized; however, these data do not distinguish between the rural area and the urban area of the city.

For the year 2018, the data are presented in Table 3, which shows the disparity in access to services between the rural area and the urban area of the city, mainly between sewerage, gas, Internet and garbage collection services, with the rural area being the one with the greatest lack of services, especially gas and Internet service. Likewise, Table 4 shows the water used by the inhabitants of Tunja go to prepare their food, showing that although the public aqueduct is the most common source, there are still cases of using sources that are not healthy and safe for health.

The maps provided (Figure 7) illustrate the areas of Tunja according to the availability of basic services such as electricity and water. In the electricity map, neighborhoods with fewer properties served by electricity are shown in red, primarily located on the outskirts, while areas with greater coverage are shown in yellow in the center. Similarly, the water map shows that neighborhoods in the peripheral zones, shown in dark blue, have less access to water services than the more central areas, shown in light blue. These maps highlight the disparities in basic infrastructure and suggest a concentration of services in the more developed and central areas of the city, while the outskirts face significant limitations in accessing essential resources.

This analysis of the distribution of basic services in Tunja raises important questions about urban equity and planning. The clear division between the central areas and the outskirts suggests that there may be a need to review and adjust urban planning policies to ensure that basic services, so essential to quality of life, are distributed more equitably. Infrastructure development should focus not only on meeting the needs of densely populated and economically active areas but also on improving conditions in less developed areas. This is critical to promoting more inclusive and sustainable urban growth that benefits all city residents, regardless of their geographic location.

Likewise, the housing deficit in the rural area for the year 2020 exceeds that of the municipal seat, i.e., the majority of the rural population of the city of Tunja lives in unfavorable conditions for their safety and quality of life.

According to data from the Rural Agricultural Planning Unit (UPRA, by its acronym in Spanish), for the year 2019 the number of allegedly informal properties throughout the Colombian territory was approximately 2,365,011, with Boyacá and Antioquia being the departments with the highest percentage of informality (Table 6).

The informality index of land tenure in Colombia refers to possible informal rural areas. It is linked to criteria that determine whether this condition exists or not. Therefore, this index is an input in the territorial planning process, especially in rural areas of the country (UPRA, 2020).

One of the proposals of the National Development Plan for 2022-2026 regarding the informality of land tenure is to design and implement a comprehensive resettlement strategy that includes not only legalization but also urban control, in the same way this strategy aims to improve housing in human settlements as long as they are on habitable land.

It also proposes the implementation of financial procedures and mechanisms focused on the resettlement of the population living in high-risk areas is proposed. Some of these mechanisms are the promotion of the supply of social housing, family housing subsidy, democratization of credit for access housing solutions, housing provision and improvement.

In this regard, the Town Hall of Tunja for the year 2021 only recognized four settlements, despite the informality of the land in the city, which are named in the diagnostic phase of the Tunja 2023-2035 territorial planning plan. These settlements are located in the rural area close to the urban area and are characterized by their lack of access to public services, which affects the environmental and health order as well as by fragile construction structures that pose a risk in the event of a seismic event or environmental failure (Alcaldía Mayor de Tunja, 2021b), however, each of these settlements have different conditions.

The data presented below refer to the following rural settlements: Runta village settlement, Pirgua village settlements in the Villa del Rosario sector, La Cascada sector and special mining reserve sector. Figures 8 and 9 show the number of houses in the villages of Runta and Pirgua, respectively, that have services such as electricity, natural gas, aqueduct, garbage collection, sewage and Internet.

According to the information from the Town Hall of Tunja (Alcaldía Mayor de Tunja, 2021a), Runta had a total of 226 houses, 915 people and 306 houses by 2021. I.e., of the 306 houses, more than half had electricity and water service; however, less than 20% of houses had access to natural gas and garbage collection service, and even less than 10% had sewage and Internet service.

Regarding Pirgua, in 2020 it had a population of 599 people, 171 houses and 219 homes (Alcaldía Mayor de Tunja, 2021a). The majority of these houses (more than 65%) had electricity and aqueduct, while about less than 10% of the houses had sewage, natural gas, garbage collection and Internet services.

Table 7 groups some of the main problems of the informal settlements of Tunja, which show not only the structural problems of the houses, but also the health problems of the population, since, without having a garbage collection service, they resort to burning or improper disposal. Likewise, the entire population of the Pirgua village is exposed to bad odors and infections due to the proximity to the landfill and the sewage treatment plant.

Likewise, the problems of housing and access to public services can be seen reflected in the statistics of education levels in rural areas. The data in Annex 2 show that one of the services with the lowest coverage in rural areas is Internet service which could be one factor among many in the educational level of the rural population. Table 8 shows that the majority of the rural population has only a primary education and that as the level of education increases, the number of people using the service decreases.

The study and recognition of some informal settlements in the rural area of Tunja by the municipality is fundamental in the territorial planning process, however, it is noted that within the urban area there are houses in precarious conditions both in terms of infrastructure and access to services; at first glance it can be seen that the materials that make up the structure of the houses are not stable, therefore, their situation may be affected in the event of heavy rains, seismic movements, or due to the deterioration of said materials.

The Figure 10 shows an uneven distribution of the university educated population across the neighborhoods of Tunja. The neighborhoods colored in darker shades of red indicate a higher concentration of residents with higher education, highlighting a pattern in which the central and southern areas of the city, such as Villa Universitaria, La María, and San Antonio, have a significantly higher percentage of residents with university degrees. This could be related to the proximity of educational institutions, accessibility to resources, or urban planning that favors these neighborhoods.

On the other hand, areas in lighter shades, representing a lower population with university education, are mainly located in the suburbs, such as in the neighborhoods of Mirador del Norte and Antonia Santos. This phenomenon may be influenced by several socio-economic factors, including lower incomes, limited access to educational opportunities, or a lesser prioritization of higher education in planning and community services. This map highlights the need for policies focused on improving access to higher education in less favored areas to promote a more equitable distribution of educational opportunities across the city.

Although Tunja is recognized as a university city, the map shows a remarkable contrast in the distribution of university education among its neighborhoods. While some central neighborhoods have high percentages of the population with higher education, others, especially on the outskirts, have significantly lower percentages. This phenomenon can be partly attributed to the fact that many students attending universities in Tunja come from other regions and tend not to settle permanently in the city after completing their studies. As a result, although higher education institutions attract many young people, their impact on the educational level of the permanent local population may be limited. This dynamic poses challenges for the city in terms of talent retention and equitable distribution of the educational and cultural benefits that come with being an educational hub.

When monitoring some houses located in neighborhoods that, according to Hidalgo (2014), had marginal origins, it is found that in the neighborhood of San Lázaro in 2014 there is the presence of houses with self-construction processes, without access to paved roads and located in high slope area, the structure of some houses in the neighborhoods of El Dorado and Libertador is also evident.

By 2021, the neighborhood of San Lázaro had 644 houses, all of which had access to electricity, water and sewer service, but only 74 had garbage collection and 67 had natural gas service (Alcaldía Mayor de Tunja, 2021a), i.e., more than 80% of the houses had to resort to another alternative such as firewood or propane gas, and also to find a solution for the treatment of their waste, which in some cases results in the burning of garbage or in its accumulation in an abandoned lot.

DISCUSSION

At the national level, the issue of informal settlements is linked to a tradition of violence that leads to situations of forced displacement, land dispossession, threats, and other violations of human integrity. In Tunja, some areas where people displaced by violence have settled coincide with neighborhoods of marginal origin, such as the Libertador, San Lázaro, Altamira, El Dorado, Jordán, Asís, and Obrero.

Additionally, in the conceptualization of informal settlements, their presence is often linked to the absence or low coverage of public services. However, in Tunja, although the neighborhoods are initially informal, their service coverage exceeds 90% of the urban area. Therefore, the category of "informal" would be subject only to legal elements, such as the municipal agreements of each neighborhood, which guarantee more significant social development of these spaces.

The situation in rural areas is different. Only four areas with informal settlements are recognized by the municipality. At the same time, more than 80% of the households have deficiencies and low coverage in access to basic services, which affects the economy and the health of the population. Therefore, informality is considered a primary characteristic of the entire rural area, taking into account access to services, education and housing, which is consistent with the aforementioned concepts of informal settlement and the living conditions of these spaces.

CONCLUSIONS

The socio-economic characterization of the informal settlements of Tunja is relevant, since it denotes the informal origin that most of the territory of the city has as a result of the small number of neighborhoods that have been recognized by the municipality, therefore, it is concluded that the city of Tunja until 2022 will consist mostly of consolidated illegal human settlements, since, despite the informality of its neighborhoods, not all of them present marginal conditions, since some have all the basic services, paved roads and constructions in stable materials.

Additionally, the development of the document reflects the impact that the spatial factor has on the socio-economic conditions of the population, since, in the case of Tunja, it coincides that informal settlements are found on the outskirts of the city, which they do not have access to basic services, and they are also located in areas of environmental failure, therefore. If we attended to what Bonet (2007) and Fujita and Krugman (2004) indicate regarding the study of the causes and reasons for the concentration or agglomeration in said specific areas, then, a response could be given to the inequalities found in the rural area, the concentration of poverty and the formation of settlements, with space as the main point of study.

In fact, the informal settlements recognized in Tunja reflect the agglomeration theory of Polèse and Rubiera (2009) since the presence of population in these areas can be linked to the presence of mining areas in the case of the settlements in the village of Pirgua, since it is the space with the largest number of mining titles in the city that generates employment opportunities and, therefore, urbanization.

Regarding the houses in the urban area that are not considered informal settlements, it is concluded that although they are located in neighborhoods with municipal consent or are not subject to any illegal, marginal or informal designation, they have weak structures and difficult access to public services, as in the case of San Lázaro.

However, the diagnostic document carried out by the municipality in 2021 only refers to the informality of the neighborhoods but not to the informality of the buildings or houses found in them, but the case of neighborhoods like Antonia Santos that until 2021 did not have a municipal agreement, even though it is a neighborhood built with national and municipal resources, therefore, the houses comply with construction standards to be habitable. That is, the non-legal status of the neighborhoods does not imply that their constructions are informal or outside the law; however, the percentage of illegal constructions in the city is unknown.

Finally, the paper clarifies the use of the terms informal settlements and marginal settlements in the article; these terms were used because of the bibliography found referred to uninhabitable areas or areas with dangerous living conditions in such a way, however, the words informal and marginal can generate stigmatizing actions against the inhabitants of the settlements, which is contrary to the objective of this article, which aims to contribute to the process of recognition of these areas, taking into account that the inhabitants of these spaces deserve to be heard and accompanied in order to achieve full respect for their rights.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

To the evaluating jury and to the editorial committee of the Apuntes del CENES Journal.

FUNDING

This research did not receive any financial support.

DECLARATION OF CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

AUTHORS' CONTRIBUTION

Authors' contributions are equal. This article is adapted from the first author's undergraduate monograph.

REFERENCES

[1] Alcaldía Mayor de Tunja. (2021a). Geobarrios. POT Tunja. http://pot-tunja.gov.co/index.php/barrios/

[2] Alcaldía Mayor de Tunja. (2021b). Diagnóstico, Plan de Ordenamiento Territorial 2023-2035. https://tic.tunja.gov.co/documentospot/4.DIMENSIONES/2.Dim.Economica/V.1/2.Diagnostico_v1.pdf

[3] Andion, C., Serva, M., Cazella, A. A., & Vieira, P. F. (2009). Space and Inequality. Administrative Theory & Praxis, 31(2), 164-186. https://doi.org/10.2753/ATP1084-1806310202

[4] Bonet, J. (2007). Geografía económica y análisis espacial en Colombia. Repositorio Banco de la República. https://repositorio.banrep.gov.co/bitstream/handle/20.500.12134/9289/LBR_2008-1.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y

[5] Buzai, G. & Baxendale, C. (2010). Análisis espacial con sistemas de información geográfica. Aportes de la geografía para la elaboración del diagnóstico en el ordenamiento territorial. En Actas I Congreso Internacional sobre Ordenamiento Territorial y Tecnologías de la Información Geográfica, Universidad de Alcalá de Henares, Alcalá. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/298352751_Analisis_Espacial_con_Sistemas_de_Informacion_Geografica_Aportes_de_la_Geografia_para_la_elaboracion_del_Diagnostico_en_el_Ordenamiento_Territorial

[6] Cárdenas, J. I. & Vallejo, L. E. (2016). Agriculture and Rural Development in Colombia 2011-2013: An Approach. Apuntes del Cenes, 35(62), 87-123. https://doi.org/10.19053/22565779.4411

[7] Cazzuffi, C. (2017). Desigualdad territorial y migración interna en México. México Social. https://www.mexicosocial.org/desigualdad-territorial-y-migracion-interna-en-mexico/

[8] Concejo Municipal de Tunja. (2001). Acuerdo Municipal 0014 de 2001, por el cual se adopta el Plan de Ordenamiento Territorial del Municipio de Tunja. https://www.asocapitales.co/wp-content/uploads/2020/11/Tunja_Acuerdo0014_POT_2001.pdf

[9] Constitución Política de Colombia. (1991). Constitución Política. http://www.secretariasenado.gov.co/constitucion-politica

[10] Czytajlo, N. (2017). Desigualdades socioterritoriales y de género en espacios metropolitanos. Bitácora Urbano Territorial, 27(3), 121-134. https://doi.org/10.15446/bitacora.v27n3.66484

[11] DANE. (2005). Censo general 2005. https://www.dane.gov.co/index.php/estadisticas-por-tema/demografia-y-poblacion/censo-general-2005-1

[12] DANE. (2018). Censos nacionales de población y vivienda. http://systema59.dane.gov.co/bincol/rpwebengine.exe/PortalAction?lang=esp

[13] DANE. (2020). Déficit de vivienda (cuantitativo-cualitativo-habitacional). https://dane.maps.arcgis.com/apps/MapSeries/index.html?appid=bacb0298984e4be98ea28ca3eb9c6510

[14] DANE. (2023). Estadísticas vitales: Nacimientos y defunciones en Colombia 2022. https://www.dane.gov.co/estadisticas-vitales-2023

[15] Davis, M. (2006). Planeta de ciudades miseria. Ediciones Akal.

[16] Echeverri, A. & Orsini, F. M. (2010). Informalidad y urbanismo social en Medellín. Universidad EAFIT.

[17] ECLAC. (2016). La matriz de la desigualdad social en América Latina. https://www.cepal.org/es/publicaciones/40668-la-matriz-la-desigualdad-social-america-latina

[18] ECLAC (2017). Panorama multidimensional del desarrollo urbano en América Latina y el Caribe. http://hdl.handle.net/11362/41974

[19] ECLAC. (2021). Introducción a la desigualdad territorial. https://igualdad.cepal.org/sites/default/files/2022-02/DB_intro_territorial_es.pdf

[20] Fernandes, E. (2011). Regularización de Asentamientos Informales en América Latina. Lincoln Institute of Land Policy. http://librodigital.sangregorio.edu.ec/opac_css/index.php?lvl=notice_display&id=2079

[21] Francis, J. M. (2002). Población, enfermedad y cambio demográfico, 1537-1636. La demografía histórica de Tunja: una mirada crítica. Fronteras de la Historia: Revista de Historia Colonial Latinoamericana, 7(7), 13-76. https://dialnet.unirioja.es/servlet/articulo?codigo=7138162&info=resumen&idioma=ENG

[22] Fujita, M., & Krugman, P. (2004). La nueva geografía económica: pasado, presente y futuro. Investigaciones Regionales, (4), 177-206.

[23] George, P. (1983). Geografía de las desigualdades. Oikos-Tau Ediciones.

[24] Gómez, G. (2010). Desplazamiento forzado y periferias urbanas: la lucha por el derecho a la vida en Medellín. Repositorio Digital FLACSO. http://repositorio.flacsoandes.edu.ec/handle/10469/1818

[25] Haggett, P., Von Thunen, J. H., Wartenberg, C. M., Hall, P., Christaller, W., Baskin, C. W., & Zipf, G. K. (1967). Three Pioneers in Locational Theory: Review. The Geographical Journal, 133(3), 357. https://doi.org/10.2307/1793549

[26] Hidalgo, A. (2012a). Morfología urbana y actores claves para entender la historia urbana de Tunja en el siglo XX. Editorial Universidad de Boyacá. https://doi.org/10.24267/9789588642260

[27] Hidalgo, A. (2012b). Tunja: primera modernización, aniversarios y obras públicas (1905- 1939). Editorial Universidad de Boyacá. https://doi.org/10.24267/9789588642277

[28] Hidalgo, A. (2014). Tunja: transformación urbana a partir de la vivienda obrera (1940-1957). Editorial Universidad de Boyacá. https://doi.org/10.24267/9789588642567

[29] Isard, W. (1949). The General Theory of Location and Space-Economy. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 63(4), 476-506. https://doi.org/10.2307/1882135

[30] Ley 2044 de 2020, Por el [sic] cual se dictan normas para el saneamiento de predios ocupados por asentamientos humanos ilegales y se dictan otras disposiciones. 30 de julio de 2020. Diario Oficial 45220. 11. https://www.funcionpublica.gov.co/eva/gestornormativo/norma.php?i=159967

[31] Londoño Toro, B. (2004). Bogotá: una ciudad receptora de migrantes y desplazados con graves carencias en materia de recursos y de institucionalidad para garantizarles sus derechos. Estudios Socio-Jurídicos, 6(1), 353-375. http://www.scielo.org.co/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S0124-05792004000100011&lng=en&nrm=iso&tlng=es

[32] ONU-Habitat. (2018). Hacer de los asentamientos informales parte de la ciudad. http://onuhabitat.org.mx/index.php/hacer-de-los-asentamientos-informales-parte-de-la-ciudad

[33] Pérez, A. & Córdoba, R. (2019). Reasentamiento integral de los desplazados: vivienda, comunidad y territorio Análisis de casos aplicables a la situación postacuerdo en Colombia Integral. En XI Seminario Internacional de Investigación en Urbanismo, Barcelona. https://doi.org/10.5821/SIIU.6632

[34] Polèse, M. & Rubiera, F. (2009). Economía urbana y regional, introducción a la geografía económica. Civitas.

[35] Portilla Tarazona, J. A. (2021). Asentamiento indígena de Hunza anterior a la conquista. Una mirada desde los imaginarios. Historia y Memoria, 22, 399-432. https://doi.org/10.19053/20275137.N22.2021.12097

[36] Romero, T. (2019). Favelas y cinturones de miseria en América Latina. El Orden Mundial. https://elordenmundial.com/favelas-cinturones-miseria-america-latina/

[37] Sasaki, Y., & Box, P. (2003). Agent-Based Verification of von Thünen's Location Theory. Journal of Artificial Societies and Social Simulation, 6(2).

[38] Techo Colombia. (2016). Derecho a Bogotá, informe de asentamientos informales. http://datos.techo.org/dataset/0db2b006-9005-4a50-a6b2-f61da2a55d3b/resource/efcc73c8-a25c-42f7-bac4-dbbae1f304c5/download/colombia-derecho-a-bogota-informe-de-resultados.pdf

[39] Techo Latam. (2021). Por una América Latina con ubicación formal para todas y todos. https://techo.org/ubicacion-formal-para-todos/

[40] Trívez, F. (2004). Economía espacial: Una disciplina en auge. Estudios de Economía Aplicada, 22(3), 409-429. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/28134361_Economia_espacial_Una_disciplina_en_auge

[41] Unidad de Paz. (2000, 28 de abril). Narcotráfico, motor del conflicto: ONU. El Tiempo. https://www.eltiempo.com/archivo/documento/MAM-1292839

[42] Unidad para las Víctimas. (2023). Registro Único de Víctimas (RUV). https://www.unidadvictimas.gov.co/es/registro-unico-de-victimas-ruv/37394

[43] Unidad de planificación Rural Agropecuaria UPRA. (2020). Informalidad de la tenencia de la tierra en Colombia 2019. https://upra.gov.co/es-co/Publicaciones/Informalidad_ten_tierra_Colombia_2019.pdf#search=indicedeinformalidaddelatierra.

[44] Uribe, H. (2011). Los asentamientos ilegales en Colombia: las contradicciones de la economía-mundo capitalista en la sociedad global. Revista de Estudios Latinoamericanos, (53), 169-200. https://www.scielo.org.mx/scielo.php?pid=S1665-85742011000200009&script=sci_abstract&tlng=pt

[45] Vázquez, M. (2019). Asentamientos humanos invisibles. WRI México. https://wrimexico.org/bloga/asentamientos-humanos-invisibles

[46] Velásquez-Castañeda, C. (2013). Intervenciones estatales en sectores informales de Medellín. Experiencias en mejoramiento barrial urbano. Bitácora Urbano Territorial, 23(2), 139-146. http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=74830874017

[47] Wekesa, B. W., Steyn, G. S., & Otieno, F. A. O. (2011). A Review of Physical and Socio-Economic Characteristics and Intervention Approaches of Informal Settlements. Habitat International, 35(2), 238-245. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.HABITATINT.2010.09.006

[48] World Bank. (2023). Población que vive en barrios de tugurios (% de la población urbana). Colombia | Data. https://datos.bancomundial.org/indicador/EN.POP.SLUM.UR.ZS?end=2020&locations=CO&skipRedirection=true&start=2000&view=chart&year=2020