Fiscal reality

of the municipalities of the department of Santander in the framework of Colombia’s fiscal decentralization

process, 2004-2012

Realidad fiscal de los municipios del

departamento de Santander, en el marco del proceso de descentralización fiscal

en Colombia, 2004-2012

Realidade

fiscal dos municípios do Santander no contexto da descentralização fiscal na

Colômbia, 2004-2012

Jorge Enrique Asela Molina *

Research article

Date of reception: 11 sep 2014

Date of approval: 13 jan 2015

Abstract

This document explores the

decentralization process in Colombia through its normative framework and its

relationship to the public finances of the municipalities of the department of

Santander, by means of the analysis of the fiscal situation of local authorities

of the department during 2004-2012. For this exercise, the indicators of

intergovernmental dependence and fiscal effort have been used for reference, as

proposed by the National Department of Planning (DNP, by its acronym in

Spanish), showing, in most cases, problems in the generation of internal

resources and a high degree of dependence on transfers from the central

government.

Keywords: decentralization, the state, local

authorities, intergovernmental dependence, fiscal effort, Santander Department.

Clasificación JEL: E62, H11, H72, K00, R58.

Resumen

Este

documento explora el proceso de descentralización en Colombia desde su marco

normativo y su relación con las finanzas públicas de los municipios del

departamento de Santander, por medio del análisis de la situación fiscal de los

entes territoriales del departamento durante 2004-2012. Para este ejercicio se

toman como referencia los indicadores de dependencia intergubernamentales y

esfuerzo fiscal, planteados por el Departamento Nacional de Planeación (DNP).

Se evidencian, en la mayoría de los casos, problemas en la generación de

recursos propios y un alto grado de dependencia de las transferencias del Gobierno

central.

Palabras claves: descentralización, Estado, entes territoriales, dependencia

intergubernamental, esfuerzo fiscal, departamento de Santander.

Resumo

Este artigo

explora o processo de descentralização na Colômbia através do quadro

regulamentar que converge e sua relação com as finanças públicas dos municípios

de Santander, que através da análise da situação fiscal das autoridades locais

do departamento durante o período entre os anos de 2004-2012

, o exercício realizado com base nos indicadores de dependência e de

esforço fiscal intergovernamental levantada pelo Departamento Nacional de Planejamento

(DNP ), mostrando na maioria dos casos os problemas na geração de recursos

próprios e alto grau de dependência das transferências do governo central.

Palavras

chave: Descentralização, Estado, Entidades Territoriais, Dependência,

esforço fiscal, Santander.

INTRODUCTION

In Colombia, the development model of

the state has revolved around a highly centralized structure, which started to

show changes in the last two decades of the 20th century, as a response to the

crises that took place in the economic, political, and social sectors. These

events, added to the international tendency that fostered an alternative to

centralization as a management model for the state, allowed for the emergence

of a decentralization model in Colombia, as an option to fulfill the aforementioned

role. The decentralization process, which showed significant progress during

the eighties, would take root in the nineties with the proclamation of the

Political Constitution of 1991, an event that gave subnational entities certain

political, administrative, and fiscal autonomy (Asela,

2014).

As from the theoretical perspective

of the decentralization process, this document shows, from a normative point of

view, the evolution of the decentralization process in Colombia and its influence

on the public finances of the municipalities of the department of Santander, in

the period between the years 2004-2012. Its objective is to describe the fiscal

reality of the municipalities of the department of Santander during this period,

through the behavior of the intergovernmental dependency and fiscal effort

indicators suggested by the National Department of Planning (DNP, from now on).

The analysis of the document is

conducted in order to show the way in which the fiscal decentralization process

in Colombia has affected the public finances of the municipalities of

Santander, indicating the degree of influence the central government has over

municipal finances, and highlighting the capacity of local authorities to

generate internal resources.

The methodology implemented for the analysis of the

fiscal reality of the municipalities of the department of Santander focuses on

the study of the indicators of fiscal performance – intergovernmental

dependence and fiscal effort- suggested by the DNP during the period between

2004 and 2012. Three categories are presented for each indicator in order to

state the behavior of the municipalities in a descriptive manner:

intergovernmental dependence (no dependence, moderate dependence, total

dependence); fiscal effort (outstanding, good, bad).

In the first part of the document the

decentralization model is presented as a structure for the management of the

state, as from a theoretical perspective. In the second part, the

decentralization process in Colombia is explained, founded on the normative

framework, mainly in the fiscal field. Finally, an analysis of the fiscal

reality of the municipalities of the department of Santander between 2004 and

2012 is carried out, based on the description of intergovernmental dependence

and fiscal effort indicators.

DESCENTRALIZATION

One

of the most common definitions of decentralization is the one suggested by Rondinelli, McCullough, and Johnson (1989), which describes it as a

political-administrative reform, and defines it as “the transfer of responsibilities

of planning, management, and the raising and allocation of resources from the

central government and its agencies to territorial units” (Rondinelli

et al., 1989, p. 58-59); the aim of which is to increase the efficiency of the

public administration. At the same time, the authors make reference to the

existence of four types of decentralization: deconcentration, delegation, devolution, and privatization. First,

they present deconcentration as the transfer of

responsibilities of an administrative nature from the higher levels of central

Government to the lower levels. Delegation is understood as the handing over of

faculties to achieve greater administrative autonomy, but with financial

responsibilities over public policies, always restricted by accountability to

the central Government. Devolution is proposed as the transfer of authority and

financing from the highest level of Government to subnational agencies, which gives

the power to collect revenue through tax. Privatization consists of the

competition between public and private agencies to provide goods and services.

Over time, the evolution of the definition of the term

‘decentralization’ developed by Rondinelli et al., (1989), has led to the redefining

of the types of decentralization proposed by the aforementioned authors, and

has achieved academic consensus in “devolution” as a type of decentralization,

and in deconcentration and delegation as

characteristics of the same process (Mardonez, 2008).

For this reason, within the framework of the structural organization of states,

decentralization in more recent times has been understood as a

political-administrative process, which consists of the transfer of

responsibilities, resources, and functions from the central body of the state

towards its local authorities (Triesman, 2002).

According to Finot (2002), the

process of decentralization, as a structure for the management of the state,

has a series of objectives in the different fields of public administration,

which focus, firstly, on the political sphere, as a basis for further steps in

the administrative and fiscal fields. For Finot (2002),

the main objectives of the process of decentralization in this phase are: 1) to

generate constructive participation, 2) to increase the efficiency of the

public administration, and 3) to achieve greater territorial and social equity.

To reach these objectives, there are fundamental

factors, such as the expansion of decision centers, improved agility and

flexibility in the making of decision by the state regarding localities and an

opening towards political plurality. These measures presuppose, among other

things, better reading of the preferences of individuals, given the proximity

of local authorities and their communities, as well as a more agile

intervention in the problems that arise in localities, with the aim of

increasing the efficiency of the public administration, which is the main

objective of decentralization (Baguenard, 1994).

The decentralization process of the state can be assumed

from different perspectives or as a conglomerate of them. Cohen and Peterson

(1996) classify them according to their characteristics as: spatial, market,

political, and administrative decentralization.

- Spatial decentralization: is understood as the transfer of resources and instruments to

local authorities, with the aim of promoting economic and industrial

activities in an attempt to impede the concentration of said activities in

the main urban centers.

- Decentralization towards the market: is viewed as the transference of responsibilities regarding the

provision of goods and public services from the state to the private

sector.

- Political decentralization: lies in the free election of local authorities, in most cases by

popular vote, at the same time that these authorities have the power to

make decisions related to the development of their localities.

- Administrative decentralization: consists of the transfer of functions, resources, and decision

making capacities from the central government to local authorities, with

the objective of guaranteeing the provision of certain public goods and

services.

Administrative decentralization is manifested in: (i) deconcentration,

(ii) delegation and (iii) devolution. (i) Deconcentration

is taken to be the redistribution of decision making authority from the central

Government towards local authorities or public entities. It is a process that

takes place within an organizational unit, with a single unit of command and management, in addition it can take place in different

levels of Government (central, departmental, municipal). (ii) Delegation, as its name indicates, allows for the delegation

of faculties that grant greater administrative autonomy along with financial

responsibilities over public policies, while remaining accountable to the

central Government. Finally, (iii)

devolution consists of granting political autonomy to the two previous

processes –deconcentration and delegation- allowing

local governments to make decisions on developmental policies within their localities.

It is necessary to add one more classification to the

different manifestations of the decentralization model: fiscal

decentralization. This includes characteristics of administrative

decentralization that make them seem similar, given that both have as their

basis the transfer of resources; although there is a substantial difference

between them: the autonomy of local governments to formulate new taxes. In the

words of Falleti (2005): “fiscal decentralization

refers to a set of policies designed to increase the revenue or fiscal autonomy

of subnational governments” (Falleti, 2005, p.329).

Or, as Schneider (2003) puts it: “it refers to how

central governments hand over part of the fiscal impact to non-central

government entities” (Schneider, 2003, p.33).

According to what was previously mentioned,

decentralization can be understood as the transfer of competences from the

central Government to subnational entities, which should be accompanied by

basic conditions on the political, administrative, and fiscal level, allowing

them to assume some of the functions of the central entity.

NORMATIVE

FRAMEWORK OF DECENTRALIZATION IN COLOMBIA, FIRST STEPS AND ITS PHASES

(1983-1990), 1991 ONWARDS

First steps towards

decentralization in Colombia

Decentralization is a form of organization of the

state, in which the public administration is organized between the central

Government and subnational governments, which have tributary faculties and

expenditure allocation. This system allows for the decision-making process to

be closer to the citizen, that is to say, that it presupposes a nearing to the

power structures by the citizens. This is translated into a better

understanding of their preferences as regards public goods and services. It is

considered that a decentralized system leads to efficiency, effectiveness, and

commitment in the administration of resources and the agencies of the state (Falleti, 2005).

In Latin America, the decentralization process began

late, in comparison to other regions-the end of the eighties and beginning of

the nineties of the XX century- due to the centralist legacy inherited from colonial

times. At the beginning of the eighties, the centralist model was losing ground

in Latin America, as a consequence of the fall of the military dictatorships

that governed many of the countries of the region, after their fall and return to

democracy, reforms started to take place which transformed the panorama for

subnational entities, among which are the election of local authorities by the

people and the delegation of administrative functions from the central

Government.

Colombia is one of the countries that from the

beginning of the eighties has been consolidating the

process of decentralization towards territorial governments. The failure in the

coverage and the quality of public services (health and education) motivated

this process for which the Political Constitution established greater fiscal

and political autonomy for subnational governments, where intergovernmental

transfers and the strengthening of local democracy play a fundamental role.

For Porras (2005),

decentralization, understood as a dynamic process, has been consolidated

through the history of the country, based on principles like: specialization,

through the definition of powers between levels of government; sustainability

in the allocation of sources of revenue, as a guarantee of the correct

management of new responsibilities; responsibility in the political sense of

establishing a commitment between the government and its electors; and integral, given the convergence of

instruments in areas of a fiscal, political, and institutional nature.

According to Lleras and

Posada (1991), in fiscal terms decentralization in Colombia has its origins in

the government of Lleras Restrepo

(1966-1970). Firstly, Law 33 of 1968, in which the strengthening of sectional tax

authorities was established, allowing for the

participation of local authorities in a percentage of the tax on sales.

Secondly, with Law 46 of 1971, which was introduced after the so called

Musgrave Mission [1] that among its

conclusions suggested the need to increase the number of public goods and

services that the state should provide, and it was recommended that said

provision was carried out directly from the departments. It is for this reason

that under this law the revenue-sharing system was created[2].

According to Iregui, Ramos

and Saavedra (2001), even if the transfers under the mechanism of the

revenue-sharing system represented an

advance in terms of decentralization, the centralist scheme was kept, given

that political power was still exclusive to the central Government. This meant

that the resources of education and health, which had been managed by the

departments, were now concentrated in decentralized national institutions, such

as the Regional Educational Fund (FER, by its acronym in Spanish) and the

sectional services of health (SSS, by its acronym in Spanish)

With the government of Turbay,

which spanned from 1978 to 1982, centralist practices and a lack of regional

autonomy were again seen as problems. In the National Integration Plan proposed

by the government, decentralization was understood as a fundamental objective of

economic policy. For this, it was necessary to establish the role of

municipalities and departments in fiscal terms and, thus, allocate a better use

of their tributary base, which would generate a decrease in the dependence on

national transfers, which would take place years later.

First phase of descentralization in Colombia (1983-1900)

The first decentralization phase in Colombia was

established in the period from 1983 to 1990; it began with Law 14 of 1983,

which sought for fiscal decentralization through reforms in the structure of

municipal and departmental taxes, which would result in the strengthening of subnational

public finances. Among other reforms, the base and the rate of tax for industry

and commerce, and taxes on liquor and cigarette consumption were modified, as

well as transferring the stamp duty on motor vehicles to the departments. As a

consequence of this law, an update of the property tax base took place and road

and transit taxes were adopted; reforms that meant that this law was known as

the National Taxation statute.

This distribution of the state’s fiscal structure

among the different levels of government -mentioned above in Law 14 of 1983-,

for Lleras (1991) obeys two basic criteria: “economies

of scale in the management of taxes and the effective capacity to control

revenue collection” (Lleras & Posada, 1991, p.

64). From this, the nation should

collect on activities of mobile factors of production of the regions.

In later years, the role of the departments was

redefined, through the laws 22 of 1985 and 3 of 1986, where they were established

as intermediate instances in charge of participating and supervising the

creation and execution of the development plan.

According to Porras (2005),

in 1985, with Law 75 the regional councils of economic planning (CORPES, by its

acronym in Spanish) were created, becoming the main entities for regional planning.

With this, the strengthening of local planning, participation in the

development plans and the programming of the budget of regional entities was intended.

These objectives and norms were confusing, which was translated into a duplicity of roles and expenditure.

By the end of the eighties, great advances took place

in the political, administrative, and fiscal fields. In the political sphere,

with the Legislative Act 1 of 1986, through which the election of mayors

through popular vote is established – a law which would come into effect two

years later-, the objective was to strengthen local governments and make them

sensitive to the preferences of their inhabitants. Concerning the

administrative field, Law 12 of 1986 modified the percentage transferred to departments

and municipalities in value-added tax (VAT), in addition to the allocation and availability

for said resources, for which new competences were assigned. Moreover, through

Decree 77 of 1987 the central Government was authorized to fuse, reform or

liquidate entities that delivered the services within the transfer of

resources, the functional structure responsible for the delivery of public

services to a local level was established and a co-financing system was

created, as an instrument of public investment.

Afterwards, in 1989, also in the administrative field,

with Law 29 the power to appoint teachers and additional staff in public

schools was given to mayors, without affecting the finances of the localities,

given that the payment of those appointments would be through the central

government. With Law 57 of 1989, the Financiera de Desarrollo Territorial (Financial Institution of

Territorial Development –FINDETER, by its acronym in Spanish) was created, as

an organ to accompany and finance urban infrastructure projects on a local and

regional level.

On the other hand, in the fiscal field, the

co-financing system was established, as an instrument for public investment

(Decree 77/87), and with Law 44 of 1990 a unified property tax was structured,

authorizing councils to establish tariffs within a certain range, which would

generate more resources for local governments.

The reforms formulated in the first phase of the

decentralization process in Colombia had two objectives. According to Iregui, Ramos and Saavedra (2001), the first was the Government’s

desire to remove the responsibility of local expenditure from their budget,

given that it was facing a crisis and the deterioration of the national

finances. The second referred to the purpose of widening the coverage, as well

as improving the efficiency and quality of public expenditure, in which the

departments and municipalities would begin to play an important role. In

summary, this stage was characterized by setting the groundwork that would

strengthen the decentralization process in Colombia, presenting great advances

in the political, fiscal, and administrative planes.

Second phase of descentralization in Colombia, 1991 onwards

The second phase of the decentralization process in Colombia started

with the promulgation of the 1991 Constitution, which introduced substantial

changes to the decentralization process with regard to territorial and

political orientation, the distribution of powers and functions among the

different levels of government, the distribution of resources among the

different levels of government, planning and public budgetary processes, and

fiscal control systems.

The new Constitution (1991), in article 1, organized the country into a

“unitary, decentralized republic with autonomy of its local authorities…” It

also suggests in article 303, making reference to political decentralization, the election of governors through popular vote.

As regards the political-administrative division of the country, a

municipality is defined in article 311 of the Constitution as:

“The fundamental entity of

the political-administrative division of the state, the responsibility of which

is to provide those public services determined by law, to construct the works

required for local progress, to arrange the development of its territory, to

promote community participation, the social and cultural betterment of its

inhabitants, and to execute the other functions assigned to it by the

Constitution and its laws.”

With regards to territorial organization, possibilities were opened up to

create new territorial entities, such as:

·

Regions

·

Provinces

·

Special districts

·

Metropolitan areas

·

Indigenous territories

All these new territorial entities, according to article 287, have total

autonomy within the limits of the Constitution and the law, which guarantees

that they are governed by their own authorities. In addition, the participation

of the central Government regarding revenues is established as well as the

possibility to generate internal resources that allow them to fulfill their

functions within the framework of their powers.

On the fiscal plane, the collection of taxes by territorial entities so

as to fulfill the functions imposed in article 287 was established within the

framework of greater fiscal autonomy. Through article 362, the nation is

impeded from appropriating the resources that are collected by the territorial

entities through taxes, except in the case of an external war, and sets out the

prohibition of surcharges or exemptions to the law in relation to property

taxes (article 294).

Intergovernmental transfers, as supplements to the

budget of territorial entities, play an important role in the development of

the localities. For this, the Political Constitution of Colombia establishes the

transfers to the departments in article 356, and in article 357, the transfers

to municipalities, at the same time, articles 360 and 361 deal with topics

corresponding to the royalties.

What was stipulated in articles 356, 357, 360, and

361, focuses on the use of resources from transfers. The revenue-sharing

system can only be used in programs referring to the health

and public education sectors, the transfers to the municipalities can only be

invested in the social sector, it will not be possible to give new

responsibilities to subnational entities without a prior increase in the

resources transferred. Moreover, it is suggested that the resources coming from

the exploitation of non-renewable resources should be delivered through

royalties to the territorial entities in which the exploitation is carried out or

where the products or derivatives of such exploitation are transported by sea.

After the issuance of the Constitution of 1991, the

laws that regulate it were promulgated. Law 60 of 1993 regulates what was

established in articles 151, 288, 356, and 357 of the Magna Carta concerning

the distribution and assignation of resources, and powers. In terms of

administrative decentralization, this law dictates the powers of the

subnational entities, mainly in sectors like education,

health, housing, and basic sanitation (see Table 1). In the fiscal field, among

other dispositions, it gives the National Department of Planning control of the

assignation of transfers to territorial entities. These transfers are delivered

under a formula of distribution, giving great importance to municipalities with

less than 50 thousand inhabitants and indigenous territories. For the formulas,

variables such as population, unsatisfied basic needs, local fiscal effort and

administrative efficiency are taken into consideration.

Table

1. Powers

and functions under Law 60 of 1993, social sectors

|

|

|||||

|

|

Sector |

Central

level |

Departamental

level |

Municipal

level |

|

|

|

|||||

|

|

General role |

To formulate policies. To distribute and

transfer resources of the revenue-sharing system To manage co-financing

funds. To advise local

authorities. To evaluate service provision. |

To plan, manage and

distribute resources among municipalities. To provide financial help

and advice to the municipalities. |

To provide basic

services: health and education (in the first level), drinking water and

health care, housing, and others indicated by law. |

|

|

|

|||||

|

|

|||||

|

|

|||||

|

|

|||||

|

|

|||||

|

|

|||||

|

|

|||||

|

|

Education |

It is no longer

responsible for administrative matters related to national educators. To establish salaries

according to the law. To conduct follow-up and

evaluation services. |

To plan, manage, and

coordinate educational services. To manage and train

teachers, according to the law. To gradually transfer

functions to the municipalities. To manage co-financing

funds for the municipalities with local resources. |

To manage pre-school,

primary and secondary education, according to the terms of departmental

change. To make the necessary

investments in infrastructure, equipment, and maintenance of educational

centers. |

|

|

|

|||||

|

|

|||||

|

|

|||||

|

|

|||||

|

|

|||||

|

|

|||||

|

|

|||||

|

|

|||||

|

|

Health |

To promote and coordinate

national campaigns and programs for primary health care. To develop all the other

roles established by Law 10 of 1990. |

Services are delivered

through specialized, regional and university hospitals. To conduct campaigns together

with or thanks to the central level. To develop all the other

roles established by Law 10 of 1990. |

To promote preventive treatment

and rehabilitation for patients in the first level. To promote medical

services through local hospitals and clinics, and

through activities related to environmental health. |

|

|

|

|||||

|

|

|||||

|

|

|||||

|

|

|||||

|

|

|||||

|

|

|||||

|

|

|||||

|

|

|||||

|

|

Housing |

To promote technical help

to local entities. No longer takes on

construction programs. Provides subsidies to

municipal programs. |

|

To define the regulations

for urban development. To promote and

participate in projects of social housing. To provide housing

subsidies to those in need. |

|

|

|

|||||

|

|

|||||

|

|

|||||

|

|

|||||

|

|

|||||

|

Basic health

care |

To conduct programs of

technical assistance to local authorities. To co-finance and provide

credit.

|

|

To provide services

(directly or indirectly, through contracts with the private sector). To conduct projects for

the construction and expansions of aqueducts and sewage. To guarantee the

provision of basic rural services of health, urban cleaning, sanitation of

slaughterhouses and market places. |

||

|

|

|||||

Source: chart elaborated

by the author with information from Lleras &

Posada (1991).

Law 141 of 1994 regulates what was established in articles 360 and 361

of the Constitution, created the National Endowment Fund (FNR, by its acronym

in Spanish) and the National Commission of Endowment, develops the rule of law in

receiving royalties for the exploitation of non-renewable resources and

establishes rules for liquidation and distribution. This law is an advance of

the decentralization of the state in fiscal terms, given that the

municipalities where non-renewable resources are exploited benefit directly

from these funds.

With the objective of making fiscal adjustments to the territorial

entities, given their growing operational expenditure, laws 549 of 1999, 550 of

1999, and 617 of 2000 are promulgated, with which, among other dispositions,

departments and municipalities are classified into categories according to

their population and unallocated current revenues (ICLD, by its acronym in

Spanish). In addition, it is stipulated that operational expenditures should be

covered by the revenues generated in the tax year (internal revenues).

As advances in the fiscal level

of decentralization and as a mechanism to strengthen the revenue of the

different levels of government, laws 663 of 2000, 778 of 2002, 863 of 2003, and

1111 of 2006 are promulgated, which strengthen the tributary statute and create

new taxes, such as the tax on financial transactions (GMF, by its acronym in

Spanish), which applies nationwide.

By 2001, Law 715 established the norms that will apply

in terms of the distribution and assignation of powers established by the

National Constitution, in accordance with articles 151, 288, 356, and 357, and

established other dispositions. This law reformed the participation system,

creating the General Participation System (SGP by its acronym in Spanish and

expressed thus below), which is formed of the resources that the nation

transfers, by the mandate of articles 356 and 357 of the Political Constitution

of Colombia, to the territorial entities.

For the year 2007, there was another modification of

the SGP with Law 1176. This change was made as regards the percentages available

for the sectors of health, education, basic sanitation and safe drinkable

water, general purposes and special assignations. The distribution percentages

of the resources the central Government delivers through the SGP in the

different laws are currently as follows:

Law 60 of 1993: education, 30 %; health, 25 %; safe

drinking water and basic sanitation, 20 %; sports, culture, and recreation, 5 %,

unallocated, 20 %. This last one, -unallocated- varies according to the rural

population percentage, as per article 22 of the same law.

Law 715 of 2001: education, 58.5 %; health, 24.5 %;

general purposes, 17 %. Of the 100% of the general purpose resources,

equivalent to 17% of the resources of the SGP, they are distributed in the

following sectors as follows: safe drinking water and basic sanitation, 41%;

sport, culture, and recreation, 7%; FONPET, 10%; unallocated, 42%.

Law 1176 of 2007: education, 58.5 %; health, 24.5 %; safe

drinking water and basic sanitation, 5.4 %; general purposes, 11.6 %. Of the

100% of the resources for general purposes, which are equivalent to 11.6% of

the SGP, they are distributed in the following sectors as follows: sports,

culture, and recreation and FONPET, 83%; unallocated, 17%.

Finally, Law 1530 of 2012 modifies articles 360, 361,

and Law 141 of 1994, among other provisions, creates the General System of

Royalties (SGR by its acronym in Spanish and expressed thus below). This law

represents, in some ways, a step back in the decentralization process, as that

it centralizes the resources generated through royalties and involves the

central Government in expenditure decisions regarding said resources with the

creation of the collegiate bodies of administration and decision (órganos colegiados de administración y decisión -

OCAD).

In this second phase of decentralization in Colombia,

the legal framework that constitutes it puts forward modifications which vary

the political, fiscal, and administrative aspects of the decentralization

process. In the administrative field there has been progress with the election

of mayors and governors through popular vote, with the handing over of new

functions to local governments and an increase in their powers; in the fiscal

field, the transfer and participation in revenues of the central Government

towards the territorial entities represent the main advance in this context. It

can be said that the decentralization process in Colombia, from its origins and

passing through two phases, 1983-1990 and 1991 up to the present, is a process

that has been strengthened in political, administrative, and fiscal matters,

and that aims to adapt to the problems generated by the same process.

ANALYSIS OF

FISCAL DESCENTRALIATION IN THE MUNICIPALITIES OF THE DEPARTMENT OF SANTANDER,

ACCORDING TO THE INDICATORS OF INTERGOVERNMENTAL DEPENDENCE AND FISCAL EFFORT,

PERIOD 2004-2012

The analysis that will be presented below was carried

out using the average of the intergovernmental development and Fiscal effort

indicators as reference These were prepared by the

National Planning Department (DPN) during the period 2004-2012. For this case,

it was decided to divide the municipalities into three categories, according to

the performance of their indicators, to the end that the categories have a

descriptive component in the behavior of their municipalities in relation to

the indicators suggested for the case. For the intergovernmental dependence

indicator, the categories are: no

dependence, moderate dependence, totally dependent. In the case of the

fiscal effort indicator, the categories are: outstanding, good, bad (see Table 2). It was decided to preserve the division of the provinces of the

department of Santander with the objective of presenting a more thorough view

of the regions of the department.

Table 2.

Categories according

to indicator

|

Intergovernmental development |

Fiscal effort |

||

|

If the indicator

is ≤ 49,9% |

No dependence |

If the indicator

is ≤ 49,9% |

Outstanding |

|

If the indicator is ≥ 50% but ≤ 59,9% |

Moderate dependence |

If the indicator is ≥ 50% but ≤ 59,9% |

Good |

|

If the indicator

is ≥60% |

Totally dependent |

If the indicator

is ≥60% |

Bad |

Source: elaborated

by the author.

Presentation of

the indicators

Intergovernmental

dependence

Intergovernmental dependence shows the degree of

incidence of the different levels of Government in the public finances of

localities. It is measured according to the relation between the transfers and

the royalties received by the municipality in proportion to their total revenue

(See Table 3). The indicator measures the importance of these resources for the

financing of the municipality’s programs and reflects to what extent the

municipality depends on the transfers for the financing of their development

plan and the accomplishment of their functions and responsibilities.

Fiscal effort

The capacity of localities to generate their own

resources enters in the scheme of the handing over of powers by the central and

departmental governments. Therefore, this indicator shows the steps the

municipalities have taken in order to guarantee the development of their own

policies. The fiscal effort indicator relates tax revenues as a percentage of

total revenues (see Table 3). In this way, how the municipality is financed is

measured and if it does enough to generate its own resources to finance its

programs, or if, on the contrary, the programs depend on transfers from the

nation.

Table

3. Indicators: intergovernmental dependence and fiscal

effort

|

Topic |

Indicator |

|

Intergovernmental

dependence |

Transfers + royalties /

total revenue |

|

Fiscal

effort |

Tax revenues / total revenue |

Source: Elaborated by the author based on DNP.

Department of Santander, political

division

The department of Santander is formed of six provinces

and a total of 87 municipalities. The provinces are: Comunera, García Rovira, Guanentina,

Mares, Soto, and Vélez. They are formed

as follows:

Comunera, 16 municipalities (Chima, Confines,

Contratación, El Guacamayo, Galán, Gámbita,

Guadalupe, Guápota, Hato, Oiba, Palmar, Palmas de

Socorro, Santa Helena del Opón, Simacota, Socorro, Suaita);

García Rovira, 12 municipalities (Capitanejo,

Carcasí, Cerrito, Concepción, Encino, Guaca, Macaravita, Málaga, Molagavita,

San Andrés, San José de Miranda, San Miguel); Guanentá,

18 municipalities (Aratoca,

Barichara, Cabrera, Cepitá, Charalá, Coromoro, Curití, Encino, Jordán,

Mogotes, Ocamonte, Onzaga,

Páramo, Pinchote, San Gil, San Juaquín, Valle de San

José, Villanueva); Mares, 7 municipalities

(Barrancabermeja, Betulia, El Carmen de Chucurí, Puerto Wilches, Sabana de

Torres, San Vicente de Chucurí, Zapatoca); Soto, 15 municipalities (Bucaramanga, California, Charta, El Playón, Floridablanca, Girón, Lebrija, Los

Santos, Matanza, Piedecuesta, Rionegro, Santa Bárbara, Suratá,

Tona, Vetas); and Vélez, 19 municipalities

(Aguada, Albania, Barbosa, Bolívar, Chipatá, Cimitarra, El Peñón, Florián, Guavatá, Guepsa, Jesús María, La

Belleza, La Paz, Landázuri, Puente Nacional, Puerto Parra, San Benito, Sucre,

Vélez).

Consolidated analysis of

the municipalities of the department of Santander in the period between

2004-2012

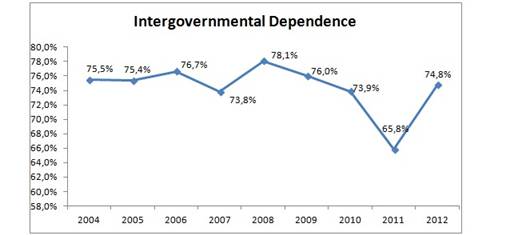

During the period studied, the behavior of

the general average of all the municipalities of the department of Santander is

not good with reference to the intergovernmental dependence indicator, as they

reached 74.4% of dependence to the national transfers. The tendency of the

indicator is solid during almost the entire period, oscillating between 73.8%

and 78.1% (see Figure 1), 2011 being the year with the least dependence of the

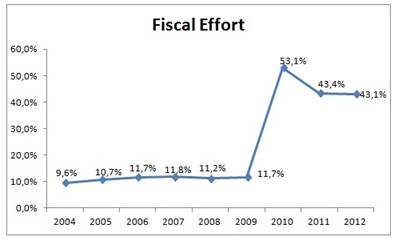

municipalities. This can be explained by the boost in the fiscal effort

indicator which, during the last three years of the period analyzed, shows good

behavior in comparison to the previous years, going from 11.7%, in 2009 to

53.1% in 2010 (see Figure 2).

Figure 1. General average of the

municipalities of the department of Santander, intergovernmental dependence

indicator (2004-2012).

Source: elaborated by the author based

on DNP data.

Figure 2. General average of the

municipalities of the department of Santander, fiscal effort indicator

(2004-2012).

Source: elaborated by the author based

on DNP data.

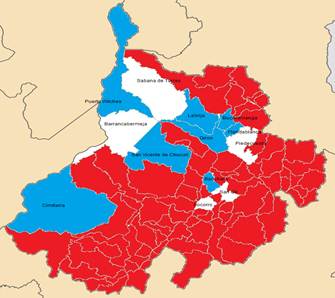

Within the

behavior of the intergovernmental dependence indicator –as we will see later

on-, of the 87 municipalities that form the department of Santander, only 13 do

not depend on the transfers of the national Government or their dependence is

moderate (see Map 1), (Bucaramanga, Barrancabermeja, Floridablanca, Girón,

Piedecuesta, San Gil, Cimitarra, Lebrija, San Vicente de Chucurí, Puerto

Wilches, Socorro, Sabana de Torres, Barichara). This is worrying, because 85%

of the municipalities during the period studied (2004-2012) are dependent on

the resources that are delivered to them through transfers and royalties in

order to fulfill their functions and responsibilities.

Map 1. Municipalities of the department of

Santander, according to the average of the intergovernmental dependence

indicator 2004-2012.

Source: map elaborated by the author based on DNP data. The municipalities are divided by

colours, as follows: white, no dependence

(Barrancabermeja, Piedecuesta, Sabana de Torres, San Gil, Socorro). Blue,

moderate dependence (Barichara, Bucaramanga, Cimitarra, Floridadblanca, Girón,

Lebrija, Puerto Wliches, San Vicente de Chucurí). Red, total dependence (74

remaining municipalities).

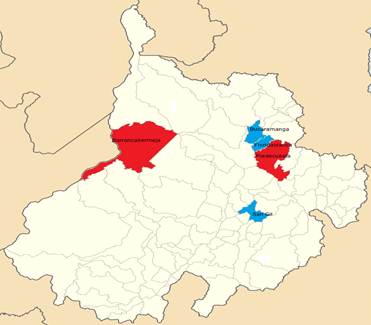

On the other

hand, the fiscal effort indicator presents an even more worrying panorama, as

only 5.7% of the municipalities of the department of Santander have an

outstanding or good effort in the generation of internal resources (see Map 2)

(Barrancabermeja, Bucaramanga, Floridablanca, Piedecuesta, San Gil), which

shows that there is still a lot to do regarding the subject. At the same time,

the behavior of the indicator impedes the improvement in the quality of life of

the inhabitants of the municipalities of the department, given that only 18% of

the municipalities have an unsatisfied basic needs (UBN) index that is lower

than 25% (see Table 13).

Map 2. Municipalities of the department of

Santander, according to the average of the fiscal effort indicator 2004-2012.

Source: map elaborated by the author based on DNP data. The

municipalities are divided by colors, as follows: red, municipalities with

outstanding fiscal effort (Barrancabermeja, Piedecuesta); blue, good fiscal

effort (Bucaramanga, Floridablanca, San Gil); white, bad fiscal effort (82

remaining municipalities).

Below there is an analysis of the indicators

per province which will show more extensively the behavior of the municipalities

of the department of Santander in the light of intergovernmental dependence and

fiscal effort indicators in the period 2004-2012.

Analysis per province

Comunera Province

The analysis of the indicators in the Comunera Province shows a pronounced dependence on the

resources of transfers and royalties of the different levels of Government. At

the same time, the generation of internal resources is really poor and cannot

guarantee the correct functioning of the municipal administrations, a situation

that can be seen in Table 4.

The intergovernmental dependence indicator shows that

out of the 16 municipalities that form the Comunera Province,

only the municipality of Socorro shows independence from the resources of the

central and departmental levels to finance their policies. On a 9-year average,

the resources from transfers and royalties were reached 44.22% of the total budgeted

revenues.

As regards the fiscal effort indicator, the Comunera Province demonstrates bad management in generating

own resources, due to the fact that none of the municipalities has an index

that shows an effort higher than 49.99%, Socorro being the closest to the goal,

with 43.99% (see Table 4).

Table 4. Municipalities

of the Comunera province according to the

intergovernmental dependence and fiscal effort indicators

|

Comunera Province |

||

|

Municipality |

Intergovernmental dependence |

Fiscal effort |

|

Chima |

85,68 % |

10,28 % |

|

Confines |

76,52 % |

20,99 % |

|

Contratación |

81,37 % |

13,67 % |

|

El Guacamayo |

81,77 % |

11,8 % |

|

Galán |

76,2 % |

13,03 % |

|

Gambita |

80,31 % |

18,47 % |

|

Guadalupe |

74,42 % |

23,04 % |

|

Guapotá |

80,26 % |

23,2 % |

|

Hato |

86,44 % |

9,61 % |

|

Oiba |

67,42 % |

30,56 % |

|

Palmar |

86,35 % |

9,84 % |

|

Palmas del Socorro |

76,8 % |

17,72 % |

|

Santa Helena del Opón |

88,15 % |

13,74 % |

|

Simacota |

79,15 % |

21,09 % |

|

Socorro |

44,22 % |

43,99 % |

|

Suaita |

69,59 % |

28,91 % |

Source: elaborated

by the author based on DNP data.

García Rovira Province

The García Rovira Province is the one that has the worst performance

in the department, as regards the behavior of the intergovernmental dependence

and fiscal effort indicators, as all of the municipalities that form it are

totally dependent on the resources of transfers and royalties delivered by the

departmental and central governments (see Table 5). The municipality of Malaga

is the closest to becoming free of such dependence with a 62.06% of their total

revenues coming from the higher levels of the Government.

Table

5. Municipalities

of the García Rovira

province according to the intergovernmental dependence and fiscal effort

indicators

|

García Rovira Province |

||

|

Municipality |

Intergovernmental dependence |

Fiscal effort |

|

Capitanejo |

78,7 % |

16,96 % |

|

Carcasí |

92,03 % |

9,07 % |

|

Cerrito |

81,02 % |

15,49 % |

|

Concepción |

78,19 % |

15,85 % |

|

Enciso |

85,96 % |

11 % |

|

Guaca |

88,85 % |

12,68 % |

|

Macaravita |

85,24 % |

10,78 % |

|

Málaga |

62,06 % |

37,32 % |

|

Molagavita |

81,88 % |

10,64 % |

|

San Andrés |

73,43 % |

21,52 % |

|

San José de Miranda |

85,44 % |

14,2 % |

|

San

Miguel |

90,77 % |

9,42 % |

Source: elaborated by the author based on DNP data.

Guanentá Province

The Guanentá Province has 18

municipalities, of which Barichara exhibits moderate

dependence in the intergovernmental dependence indicator, this being 57.83% but

concerning fiscal effort its index is 29.02%, which shows another type of

financing for the programs of its development plan. On the other hand, the

municipality of San Gil has no dependence on the resources of royalties and

transfers in financing their public policies; moreover, the fiscal effort made

by the municipality allows it to have a favorable indicator, because 57.39% of its

total revenue comes from tax revenues. The majority of the municipalities of

this province show total dependence and bad behavior in the generation of their

own resources (see Table 6).

Table

6. Municipalities

of the Guanentá province according to the

intergovernmental dependence and fiscal effort indicators

|

Guanentá Province |

||

|

Municipality |

Intergovernmental dependence |

Fiscal effort |

|

Aratoca |

76,43 % |

18,81 % |

|

Barichara |

57,87 % |

29,02 % |

|

Cabrera |

84,38 % |

12,98 % |

|

Cepitá |

92,17 % |

9,44 % |

|

Charalá |

67,24 % |

28,73 % |

|

Coromoro |

83,07 % |

15,58 % |

|

Curití |

77,8 % |

21,33 % |

|

Encino |

84,35 % |

13,09 % |

|

Jordán |

92,47 % |

8,87 % |

|

Mogotes |

82,98 % |

18,22 % |

|

Ocamonte |

78,06 % |

17,21 % |

|

Onzaga |

84,24 % |

12,78 % |

|

Páramo |

77,74 % |

25,07 % |

|

Pinchote |

71,74 % |

30,75 % |

|

San Gil |

36,51 % |

57,39 % |

|

San Joaquín |

84,81 % |

9,79 % |

|

Valle de San José |

79,3 % |

17,91 % |

|

Villanueva |

78,34 % |

18,83 % |

Source:

elaborated by the author based on DNP data.

Mares Province

The Mares Province has the best performance as regards

the intergovernmental dependence indicator in the department of Santander,

given that 57% of the municipalities of which it is formed do not show

dependence or show moderate dependence (see Table 7). Barrancabermeja and Sabana de Torres are the ones that have the best index in

the province with 35.11% for the former -the best of the department- and 42.08%

for the latter. The municipalities of Puerto Wilches

(52.3% of their total revenue) and San Vicente de Chucurí

(51.3%) show moderate dependence on the revenues from the central and

departmental levels and royalties.

Regarding

the fiscal effort indicator, the municipality of Barrancabermeja presents the best index in the province and, at the same

time, in the department: 66.7% of its total revenue corresponds to that coming

from tax collection. The other municipalities have a really poor index, a

situation that puts them in a bad position as regards the generation of internal

resources.

Table 7.

Municipalities of the Mares province according to the intergovernmental

dependence and fiscal effort indicators

|

Mares Province |

||

|

Municipality |

Intergovernmental dependence |

Fiscal effort |

|

Barrancabermeja |

35,11 % |

66,7 % |

|

Betulia |

74,03 % |

30,19 % |

|

El Carmen de Chucurí |

72,51 % |

22,03 % |

|

Puerto Wilches |

52,3 % |

30,32 % |

|

Sabana de Torres |

42,08 % |

36,34 % |

|

San Vicente de Chucurí |

51,3 % |

37,18 % |

|

Zapatoca |

60,51 % |

25,78 % |

Source:

elaborated by the author based on DNP data.

Soto Province

In the Soto Province, where Bucaramanga is located,

the capital of the department, the intergovernmental dependence indicator has

good behavior in the municipalities that form the metropolitan area of

Bucaramanga, (Bucaramanga, Floridablanca, Piedecuesta, Girón).

The municipality of Piedecuesta has an index of 46.31%,

which positions it among the municipalities with no dependence on resources of

transfers and royalties. The municipalities of Bucaramanga (50.02%), Floridablanca (52.71 %), Girón

(59.13) % and Lebrija (58.83 %) have moderate

dependence on these types of resources.

The rest of the municipalities are totally dependent (see Table 8).

As regards the fiscal effort indicator, once again the

municipality of Piedecuesta appears as the best in

the province with an index of 60.87%, showing outstanding management in the

generation of its own resources. At the same time, the municipalities of

Bucaramanga and Floridablanca demonstrate good

performance in the generation of their own resources with indexes of 56.58% and

52.71, respectively. It is important to highlight that, even though the

municipalities of Girón (47.86 %) and Lebrija (44.5 %) do not show good performance in the

generation of internal resources, their indexes are close to taking them to

that position; the municipalities have a really low index (see Table 8).

Table 8.

Municipalities of the Soto province according to the intergovernmental

dependence and fiscal effort indicators

|

Soto Province |

|

||||

|

Municipality |

Intergovernmental dependence |

Fiscal effort |

|||

|

Bucaramanga |

50,02 % |

56,58 % |

|

||

|

California |

70,48 % |

18,85 % |

|

||

|

Charta |

87,96 % |

9,61 % |

|

||

|

El Playón |

84,11 % |

19,69 % |

|

||

|

Floridablanca |

57,18 % |

52,71 % |

|

||

|

Girón |

59,13 % |

47,86 % |

|

||

|

Lebrija |

58,83 % |

44,5 % |

|

||

|

Los Santos |

69,06 % |

35,56 % |

|

||

|

Matanza |

84,28 % |

12,86 % |

|

||

|

Piedecuesta |

46,31 % |

60,87 % |

|

||

|

Rionegro |

65,22 % |

33,13 % |

|

||

|

Santa Bárbara |

85,64 % |

10,54 % |

|

||

|

Suratá |

84,09 % |

10,43 % |

|

||

|

Tona |

75,99 % |

22,92 % |

|

||

|

Vetas |

76,46 % |

15,23 % |

|

||

Source:

elaborated by the author based on DNP data.

Velez Province

The Velez Province registers the tendency of most of

the municipalities of the department in both indicators. Concerning the

intergovernmental dependence indicator, the municipality of Cimitarra

stands out, given that it is the only one that has moderate dependence in the

composition of its total revenue received through transfers and royalties (its

index is 50.45%). The rest of the municipalities are totally dependent on the

resources provided by the different levels of the government.

In the fiscal effort indicator, the entire province performs

badly, because the indexes of the indicator show an insufficient effort on the

part of the municipalities to generate greater volumes of internal resources.

It is important to highlight the progress of municipalities such as Cimitarra and Barbosa, which, given their indexes of 47.62%

and 43.67%, are the closest to performing well in the generation of resources.

Table 9. Municipalities of the Velez province

according to the intergovernmental dependence and fiscal effort indicators

|

Provincia de Vélez |

||

|

Municipality |

Intergovernmental dependence |

Fiscal effort |

|

Aguada |

85,45 % |

12,82 % |

|

Albania |

80,1 % |

11,45 % |

|

Barbosa |

67,21 % |

43,67 % |

|

Bolívar |

86,27 % |

18,16 % |

|

Chipatá |

80,5 % |

15,9 % |

|

Cimitarra |

50,45 % |

47,62 % |

|

El Peñón |

91,67 % |

8,57 % |

|

Florián |

65,62 % |

28,63 % |

|

Guavatá |

73,92 % |

19,81 % |

|

Guepsa |

74,82 % |

25,2 % |

|

Jesús María |

77,47 % |

15,99 % |

|

La Belleza |

76,41 % |

25,32 % |

|

La Paz |

84,31 % |

14,14 % |

|

Landázuri |

74,75 % |

23,26 % |

|

Puente Nacional |

64,6 % |

36,03 % |

|

Puerto Parra |

59,96 % |

34,4 % |

|

San Benito |

84,12 % |

14,63 % |

|

Sucre |

88,74 % |

12,09 % |

|

Vélez |

69,73 % |

33,08 % |

Source:

elaborated by the author based on DNP data.

After making an analysis of the indicators

per province, some peculiarities within the behavior of the indicators in the

municipalities become evident; variables like population, geographic extension,

and province, which turn out to be influential in the behavior of the

indicators in these localities.

As we have seen before, the department of

Santander has 13 municipalities that show no dependence or have moderate

dependence as regards the resources received from the central and departmental

governments through transfers and royalties. This can be explained

demographically, given that out of the 13 municipalities with the highest

population of the department (see Table 10), 11 are among the municipalities without

or with moderate dependence on these types of resources, Sabana

de Torres and Barichara being the exceptions. In

addition to this, of the 5 municipalities whose fiscal effort indicator is

outstanding or good, all of them are among the 6 municipalities with the

highest population within the department, which demonstrates a clear relationship

between population and resource generation.

Table 10. Municipalities of the department of Santander with

greater population

|

Province |

Municipality |

Population |

|

Soto |

Bucaramanga |

526056 |

|

Soto |

Floridablanca |

263041 |

|

Mares |

Barrancabermeja |

191718 |

|

Soto |

Girón |

166115 |

|

Soto |

Piedecuesta |

139178 |

|

Guanentá |

San Gíl |

44937 |

|

Vélez |

Cimitarra |

41375 |

|

Soto |

Lebrija |

36138 |

|

Mares |

San

Vicente de Chucurí |

34250 |

|

Mares |

Puerto

Wilches |

31503 |

|

Comunera |

Socorro |

30142 |

|

Vélez |

Barbosa |

27877 |

|

Soto |

Rio negro |

27775 |

Source:

elaborated by the author based on DANE data.

Another peculiarity is centered on Pening’s (2003) affirmation that the public finances of

local authorities depend on their size, that is to say that the generation of internal

resources is correlated with the size of the locality.

In the case of the municipalities of the

department of Santander, it is possible to see that, in some way, this

condition is satisfied, given that out of the 13 municipalities that do not

show dependence or whose dependence on resources from transfers or royalties is

moderate, 7 are among the 15 municipalities with greater territorial extension,

which are: Cimitarra,

Puerto Wilches, Barrancabermeja, Sabana

de torres, San Vicente de Chucurí,

Girón, and Lebrija, (see

Table 11). This shows that there is certain relationship between the size of

the municipality and its dependence on the transfers made to the localities.

Additionally, most of the municipalities without or with moderate dependence

are concentrated in the provinces of Soto (Bucaramanga, Floridablanca,

Girón, Piedecuesta, Lebrija) and Mares (Barrancabermeja, San Vicente Chucurí, Puerto Wilches, Sabana de Torres), provinces that contain the main urban

centers of the department and the municipalities with the greatest economic

activity, mainly in the municipalities of Soto Province which form the

metropolitan area of Bucaramanga and the city of Barrancabermeja. This shows

that the main development axis of the department is located in the north-east,

which can be inferred from the results of the fiscal effort indicator, where 4

out of 5 municipalities are from that area of the department (see Table 12).

Table 11. Municipalities of the department of Santander without or with moderate

intergovernmental dependence according to its territorial extension (km²)

|

Province |

Municipality |

Population |

Area Km2 |

Position according to extension |

|

Soto |

Bucaramanga |

526056 |

154 |

49 |

|

Soto |

Floridablanca |

263041 |

101 |

63 |

|

Mares |

Barrancabermeja |

191718 |

1274 |

3 |

|

Soto |

Girón |

166115 |

684 |

11 |

|

Soto |

Piedecuesta |

139178 |

481 |

19 |

|

Guanentá |

San Gil |

44937 |

150 |

51 |

|

Vélez |

Cimitarra |

41375 |

2847 |

1 |

|

Soto |

Lebrija |

36138 |

541 |

15 |

|

Mares |

San

Vicente de Chucurí |

34250 |

1104 |

7 |

|

Mares |

Puerto

Wilches |

31503 |

1588 |

2 |

|

Comunera |

Socorro |

30142 |

131 |

55 |

|

Mares |

Sabana de

Torres |

19077 |

1153 |

6 |

|

Guanentá |

Barichara |

7352 |

134 |

54 |

Source:

elaborated by the author based on DANE data.

Table 12. Municipalities of the department of Santander with outstanding or good

fiscal effort

|

Province |

Municipality |

Population |

Area Km2 |

Position according to extension |

|

Mares |

Barrancabermeja |

191718 |

1274 |

3 |

|

Soto |

Bucaramanga |

526056 |

154 |

49 |

|

Soto |

Floridablanca |

263041 |

101 |

63 |

|

Soto |

Piedecuesta |

139178 |

481 |

19 |

|

Guanentá |

San Gil |

44937 |

150 |

51 |

Source:

elaborated by the author based on DANE data.

Using the categorization of the quality of

life index for the year 2012 of the DANE (lower than 25%, higher than 25% but

lower than 50% and higher than 50%), it was found that out of the 87

municipalities that form the department of Santander, only 18 have an index

that is lower than 25%, representing 18% of the municipalities of the

department (see table 13). Of these 16 municipalities, most of them are located

in the province of Soto - Bucaramanga, Floridablanca,

Girón, Piedecuesta, Tona, Vetas- and in the

metropolitan area of Bucaramanga, which is part of the same province. Soto

Province is the one that has the best UBN, given that for the year 2012 all of it’s municipalities were below 50%, closely followed by the

province of Mares, in which only one municipality is above 50% in the index (El

Carmen de Chucurí with 51,08 %). In contrast to the

behavior of these two provinces (Soto and Mares), the remaining provinces (Comunera, García Rovira, Guanentá, Vélez) do not show a good UBN, with most of the

municipalities that form them between 25% and 49.9%. It is worth indicating

that 67% of the municipalities of the department (58) have an index higher than

25% but lower than 50%, and that only 15%, corresponding to 13 municipalities

are above 50% (see table 13).

In relation to the quality of life in the

municipalities of the department of Santander (UBN) and the indicators of

intergovernmental dependence and fiscal effort for the year 2012, a direct

relationship was found among the municipalities that have a UBN index lower

than 25% and those with a better fiscal effort indicator. Out of the 16

municipalities that have a UBN lower than 25%, 11 show outstanding or good

fiscal effort (see Table 14) and 7 out of those 11 appear among the most

populated municipalities of the department (Bucaramanga, Floridablanca,

Barrancabermeja, Girón, Piedecuesta,

San Gíl, Barbosa).

.

Concerning the relation between the UBN and

the intergovernmental dependence indicator for 2012, it is observed that half

of the municipalities (8) that have a UBN lower than 25% do not show dependence

(Bucaramanga, Barrancabermeja, San Gil, Socorro) or their dependence is

moderate (Floridablanca, Girón,

Málaga, Zapatoca), and the

rest are totally dependent (Barbosa, Charalá, Guapotá, Ocamonte, Piedecuesta, Pinchote, Tona, Vetas), (see Table 14),

which shows the importance of the resources that the central Government

delivers to the municipalities for investment in social sectors through SGP and

SGR.

Table 13. Distribution of municipalities per province

according to UBN, year 2012

|

Province |

UBN <25% |

UBN >25% but <50% |

UBN >50% |

|

Comunera |

2 |

12 |

2 |

|

García

Rovira |

1 |

7 |

4 |

|

Guanentina |

4 |

12 |

2 |

|

Soto |

6 |

9 |

0 |

|

Mares |

2 |

4 |

1 |

|

Vélez |

1 |

14 |

4 |

|

Total |

16 |

58 |

13 |

|

% |

18% |

67% |

15% |

Source:

elaborated by the author based on DANE and DNP data.

Table 14. Municipalities with UBN below

25% in relation to fiscal effort and intergovernmental dependence indicators,

year 2012.

|

Province |

Municipality |

UBN % |

Fiscal effort |

Intergovernmental dependence |

|

Soto |

Bucaramanga |

11,55 |

Outstanding |

No dependence |

|

Vélez |

Barbosa |

18,80 |

Outstanding |

Total dependence |

|

Mares |

Barrancabermeja |

22,33 |

Outstanding |

No dependence |

|

Guanentá |

Charalá |

24,08 |

Good |

Total dependence |

|

Soto |

Floridablanca |

9,43 |

Outstanding |

Moderate dependence |

|

Soto |

Girón |

15,37 |

Outstanding |

Moderate dependence |

|

Comunera |

Guapotá |

21,67 |

Bad |

Total dependence |

|

García

Rovira |

Málaga |

21,24 |

Outstanding |

Moderate dependence |

|

Guanentá |

Ocamonte |

24,79 |

Bad |

Total dependence |

|

Soto |

Piedecuesta |

14,36 |

Outstanding |

Total dependence |

|

Guanentá |

Pinchote |

22,62 |

Outstanding |

Total dependence |

|

Guanentá |

San Gíl |

11,14 |

Outstanding |

No dependence |

|

Comunera |

Socorro |

15,07 |

Bad |

No dependence |

|

Soto |

Tona |

24,10 |

Good |

Total dependence |

|

Soto |

Vetas |

20,80 |

Bad |

Total dependence |

|

Mares |

Zapatoca |

18,11 |

Bad |

Moderate dependence |

Source:

elaborated by the author based on DANE and DNP data.

The analysis of the indicators of intergovernmental

dependence and fiscal effort in the municipalities of the department of

Santander during the period 2004-2012 describes the high dependence of

municipalities on resources from transfers, given that the fiscal effort is not

strong enough to break said dependence. In the same way, the analysis

demonstrates that the best indicators of the municipalities in the department

are found in the municipalities of the metropolitan area and its influence zone

(Bucaramanga, Floridablanca, Girón,

Piedecuesta, Barrancabermeja), the ones that have the

largest populations (see Table 10), and the best quality of life (see Table

14).

CONCLUSIONS

Decentralization, as a structuring and development

model of the state, showed great progress in the last decades of the XX century.

The advances in research on the concept have allowed for the development and

consolidation of decentralization as an organization alternative for nations.

The changes in the political, administrative, and fiscal contexts have made it possible

that subnational entities have greater autonomy in decision-making processes as

regards problems that appear in their territories, considerably improving

efficiency in public administration.

In Colombia, the decentralization process was

consolidated in the nineties. The importance of this consolidation lay in the

passing of the political power to local authorities, as well as giving power

and responsibilities to the lower levels of the government. The formulation of

a normative framework which supported what was proclaimed in the Political

Constitution of 1991 became a main priority to give a solid grounding to the

process. The promulgation of laws, such as Law 60 of 1993, Law 141 of 1994, and

their modifications (Law 1176 of 2007 and Law 1530 of 2012) show the

adaptability and the steps that the decentralization process has taken in the

country.

The analysis of the intergovernmental dependence

indicator for the municipalities in the department of Santander during the

period studied showed a high level of dependence of the municipalities on the

resources that the central Government provides through SGP and royalties,

showing an average dependence over the years of the period studied, of 74.4% on

the revenues mentioned. Of the total of the municipalities, only 15% do not show

dependence on these resources, or show a moderate one. In the same way, the

provinces that have a greater level of dependence are: Velez, Guanentá, Comunera, and García Rovira, the last being the

one with the worst performance, given that all the municipalities that form it

show dependence.

The analysis of the behavior of the fiscal effort

indicator, for the municipalities of the department of Santander during the

studied period, showed a poor performance in the generation of internal

resources, exhibiting an indicator average of 22.9%. Of the total of the

municipalities that form the department, only 5.7% have an outstanding or good

fiscal effort. The province of Soto is the one that has the best performance, as

three of its municipalities are among the five which have outstanding or good

fiscal effort.

Looking at the possible relationship between the

indicators and variables, such as population, geographic extension, and quality

of life, it was found that there is a correlation between the municipalities

that have moderate to no intergovernmental dependence, given that out of the 13

municipalities in this condition, 11 are among the most populated. In the same

way, said correlation occurs with the fiscal effort indicator, because out of

the 5 municipalities with outstanding or good fiscal effort in the department,

they are all found among 6 most populated municipalities. As regards geographic

extension, 7 out of the 13 municipalities without or with moderate dependence

are among the 15 with the greatest geographic extension in the department. For

the fiscal effort indicator, there is no clear relation between geographic

extension and the fiscal effort of the municipalities.

The results between the fiscal effort indicator and

the UBN in the year 2012, indicated that out of the

total of the municipalities of the department: 16 present a UBN lower than 25%,

67 higher than 25% but lower than 50%, and 15 higher than 50%. The province of

Soto shows the best performance with 6 municipalities, of which 4 are part of

the metropolitan area of Bucaramanga (Bucaramanga, Floridablanca,

Girón, Piedecuesta).

As regards the intergovernmental dependence indicator, it was shown that the

relationship that exists between municipalities without or with moderate

dependence is not that close, given that even when half of the municipalities

with a UBN lower than 25% satisfy said condition, the other half is totally

dependent, which makes it possible to see the importance of the transfer

resources and royalties for the financing of social sectors.

REFERENCES

Asela, J. (2014). La descentralización en Colombia.

¿Realidad o espejismo? Consideraciones sobre la actualidad del proceso. Revista CEA, 1(1), 65-74.

Baguenard, J. (1994).

La décentralisation

(4 ed.). Colección: Que sais-je? no. 1879. París: Presse

Universitaire de France.

Cohen, J. &

Peterson, S. (1996). Methodological issues

in the analysis of decentralization. Cambridge, MA: Harvard Institute for International Development.

Constitución Política de Colombia (2012). Bogotá: Legis.

Departamento Administrativo Nacional de

Estadística. (2010). Estimación y

proyección de población nacional, departamental y municipal total por área

1985-2020. Recuperado de:

Departamento Administrativo Nacional de

Estadística. (2012). Necesidades básicas

insatisfechas –NBI, por total, cabecera y resto según municipio y nacional. A junio

de 2012.

Recuperado

de: https://www.dane.gov.co/files/censos/resultados/NBI_total_municipios_30_Jun_2012.xls

Departamento Nacional de Planeación. (2014). Contratos Plan. Recuperado de https://www.dnp.gov.co/Contratos-Plan

Departamento Nacional de Planeación. (2014). Desempeño Fiscal. Recuperado de https://www.dnp.gov.co/programas/desarrollo-territorial/evaluacion-y-seguimiento-de-la-descentralizacion/Paginas/desempeno-fiscal.aspx

Falleti, T. (2005). A sequential theory of decentralization: Latin American cases in

comparative perspective. American

Political Science Review. 99(3), 327-346.

Finot, I. (2002). Descentralización

y participación en América Latina: una mirada desde la economía. Revista de la CEPAL, 78, 139-149.

Garay, J. (1994). Descentralización,

bonanza petrolera y estabilización. Bogotá: FESCOL.

Iregui, A, Ramos, J. & Saavedra, L. (2001)

Análisis de la descentralización

en Colombia. Recuperado de http://www.banrep.gov.co/docum/ftp/borra175.pdf

Lleras, C. & Posada, J. (1991). Descentralización política, fiscal y administrativa después de la

Constitución de 1991. Bogotá: Presencia.

Mardonez, R. (2008). Descentralización: una definición y una evolución de la

agenda legislativa chilena (1990-2008). Revista

Eure, 34(102), 39-60.

Pening, J. (2003). Evaluación del proceso de descentralización en Colombia. Economía y Desarrollo, 2(1), 123-149.

Porras, O. (2005, abril). La descentralización en