Mujeres

en la caficultura tradicional colombiana, 1910-1970*

Renzo Ramírez Bacca[1]

Universidad Nacional de Colombia-Sede Medellín

Reception: 28/08/2014

Evaluation: 01/09/2014

Approval: 12/11/2014

Research and

innovation article.

Resumen

El texto

trata sobre la compleja y diversa dinámica laboral de la mujer en los sectores

rural y urbano de la industria cafetalera colombiana. Es una comprensión

sucinta limitada a la fase de producción del grano bajo la técnica bajo sombrío

en la zona andina durante gran parte del siglo XX. Resalta la condición de la

mujer a partir de su condición de recolectora, escogedora o tablonera.

Se trata de un enfoque descriptivo e historicista apoyado en un extenso acervo

documental y fuentes secundarias.

Palabras clave:

mujeres, trabajadoras, caficultura, Colombia.

Women in

Traditional Colombian Coffee Growing, 1910 – 1970

Abstract

This article discusses the complex and diverse labor dynamics of women

in rural and urban sectors of the Colombian coffee industry. This concise analysis is limited to the

production stage of the grain grown under shade, a technique that has been used

during a large part of the twentieth century in the Andean region; and

highlights the status of women, considering their condition as collectors,

sorters or tabloneras.

This study has a descriptive and historical approach supported by an extensive

documentary archive and secondary sources.

Keywords: workers, women, coffee growing, Colombia.

Femmes dans la

caféiculture traditionnelle colombienne, 1910-1970

Résumé

Ce texte reconstruit la dynamique complexe et diverse du travail des femmes

dans les secteurs rural et urbain de l’industrie caféière colombienne. Il

s’agit d’une étude succincte limitée à la phase de production du grain sous la

technique de la culture dite « sous l’ombre » dans la zone andine pendant une

grande partie du XXe siècle. Il souligne la condition de la femme à partir de

sa condition de cueilleuse, escogedora ou tablonera. On y entreprend une analyse descriptive et

historiciste appuyée sur un ensemble documentaire étendu ainsi que sur une

large bibliographie.

Mots-clés: femmes, travailleuses, caféiculture, Colombie.

1. Introduction

This text considers women as both actors and historical subjects in one of the most important socio-productive activities in Colombia of the 20th century: coffee cultivation. This industry was representative of the Andean agrarian sector and is characterized because it invigorated the labor practices of colonists and peasants in the zones of agricultural frontiers until consolidating the agro-industrial industry.

But, similarly, it allowed the initiation of socio-cultural processes that had no antecedents in the national agrarian history. It is the motivation to raise the question: what was the role of women during the traditional production stage of coffee grown under shade[2]?

Colombian historiography on the coffee issue in fact has different emphases and relations that are derived from economic history, sociology and anthropology. Ramírez Bacca offers a bibliographical review of the Colombian coffee industry, which reveals the non-incorporation of the problem of women and family nuclei in the classic works on coffee, but it does so with the contributions of Garzon, Meertens and Chacon, whose antecedents are Leon de Leal, García, Medrano, Arcila and Campillo[3]. As it concludes:

The vacuum is due in part to the lack of primary sources, which would allow the theme to be worked on from a historical perspective. Also, it is due to the lack of systematic research on peasant family nuclei and their employment relationship in agrarian structures. However, the concept of gender is a category of analysis that can well be identified and continue to be applied in agricultural studies[4].

It is not surprising then that

in recent years Rodríguez Giraldo[5] carried out a study in which he warns of the ideal

representations created by institutions such as the National Federation of

Coffee Growers (FNC, by its acronym in Spanish), based on the family nuclei

dedicated to coffee cultivation[6], and how instrumentalizing the category of gender contributes to the

visibility and analysis of the role of women in the rural context of the

Colombian coffee zones. The other

important text is by Ramírez Bacca

on female coffee pickers linked to the semi-industrial coffee sector in

Antioquia[7], as well as, Rodríguez Valencia's recent theses on

women and family in three Colombian coffee regions: Calarcá

and Montenegro in Quindío and Sevilla in the Department of Valle del Cauca[8]; and Suaréz Quintero on

the cultural construction of the identity of women in the town of Marquetalia, Department of Caldas[9].

Other lines of academic production

related to female rural workers in other productive sectors, the family and

Colombian labor history are not considered here[10].

Already in the Latin American sphere, grain-producing countries like Brazil and Costa Rica, stand out for certain studies that revitalize the concept and the role of women; in fact, Scott defends the importance of the gender category for historical analysis[11]. An example is provided by Grossman and Leandro, who study women in coffee production in the cases of Costa Rica and Brazil, but placing the analysis in a functionalist perspective of socio-economic development and labor and the socio-productive participation of women with statistical information[12]. Likewise, Stolcke's work with a historical-anthropological approach on women and the family in Sao Paulo farms constitutes an important reference[13].

In terms of methodology, this article develops a historical-critical approach whose sources of information are based on statistical, institutional, trade and research results. Data, of a fragmented nature, allows for an interpretative understanding, which accounts for certain functional characteristics of the socio-productive role of women. There is instead an intentionality and hermeneutical technique in order to understand the socio-cultural context of women in the traditional productive phase of coffee grown under shade. In this sense, it is a historicist representation, which, due to the limitation of the proposed time frame, does not contemplate other phenomena and recent processes in coffee zones, and, whose conceptual tools, are defined throughout the text, especially by the descriptive nature of the proposed approach.

2. Background

Analyzing the role of women in

traditional Colombian coffee cultivation means considering the population

dynamics and processes of agro-industrial experimentation[14]. We can consider, as a context, the great

transformation of the rural sector and the peasantry that began at the end of

the 19th century. McGreevey this points

out, when he indicates that a fifth of this population actually achieved its

specialization thanks to coffee between 1870 and 1930[15]. Never before in economic history had a

similar phenomenon occurred[16]. The effects of this process also implied an

agro-export specialization of the national economy, evidenced in the levels of

production and export between 1910 and 1930[17]. The

industry grew by 500%, offering unprecedented dynamism. In the same sense,

exports would not have increased without advances in the transport system,

especially the development of rail lines, aerial cable and roads leading to the

Magdalena River[18].

It was a time of prosperity in which the purchasing power of the population increased and some industrialization was achieved thanks to exports. It should also be recognized that the success of the crop was due to the excellent land and good climates, at a time when a number of towns and farms had already been consolidated, as a result of the different distribution policies of bare areas and migrations between regions.

In that process, the contribution of the family nucleus was also important, particularly for its socio-labor function. To this can be added the different funding systems and dissemination strategies developed with small and medium-sized owners.

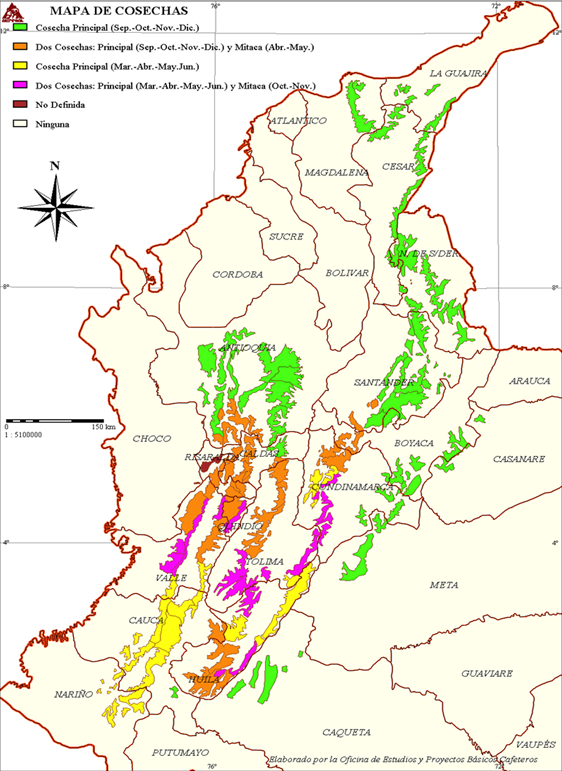

The great problem that the producers had was labor, for this same reason the employment of women and infants became a strategy that was indicated at the time, either because of the excessive use of it or because it was even insufficient in the harvesting periods of the grain. But just as the coffee crop was based on the family nucleus, numerous in progeny, as it was presented in the current area of Antioquia and the Coffee belt[19], it was necessary to engage labor in the most populated areas of the Cundiboyacense region[20]. In the same sense, the role of women was important in the semi-industrial phase of coffee, specifically in threshing machines as pickers of the grain; in part because it represents the formation of a new urban socio-labor group during the first decades of the 20th century, and because their role as coffee collectors became equally fundamental in rural areas (figure 1).

Figure 1. Map of coffee growing zones in Colombia

Source: National

Federation of Colombian Coffee Growers (FNCC, by its acronym in Spanish).

Source: National

Federation of Colombian Coffee Growers (FNCC, by its acronym in Spanish).

3. The rural

sector: tabloneras

and collectors

In the border zones of the Andean region different types of agrarian structures were configured[21], - small, medium and large properties-; which were consolidated according to the extension of the permanent crops - Coffea Arabica variety (Bourbon, Maragogipe and Typica) shaded with legumes, especially with leafy trees of guamo and carbonero. Subsistence crops-corn, arracacha, bean, etc.-were also part of the habitat, breeding pigs and cattle, and sugarcane crops, which together constituted a culture of self-sufficiency and subsistence. All this was not possible without the presence of the family nucleus.

On the large properties, the relations of sharecropping with tenant families was important[22]. In times when having a coffee plantation was a matter of prestige for a dynamic and projected sector of urban traders, they were the ones who began to set up Agricultural Societies, which were nothing more than associations of capitalist and industrial investors, ready to invest in the border areas, in the boom of certain unused land policies, which allowed them to acquire the possession of state farms under the condition of having permanent crops, or even thanks to the low cost of land in border areas[23]. This practice could only be strengthened thanks to the families of tenants, with whom different relationships were established; either because it was a customary relationship, also called the "prevailing force of tradition" in the region, or because of the impact of state regulations on sharecropping during the 20th century.

The tabloneo, as it is

commonly known, is related to the system known in some parts as partija and in

others as compañía. The landowner

offers the area for sowing and supplies the seeds, the seedlings, the necessary

tools and utensils; and the partijero - locally known as a tablonero - does the sowing and

attends to the conservation of the crops -1000 to 3000 trees. The product of

each harvest is then divided between the landowner and the tablonero, under the previously

agreed conditions[24]. In other words, the tabonero is the one who under an

oral or written contract receives a coffee plantation or tablón to administer jointly with

the landowner[25].

Gonzalo Paris, who studied the geography of the

province of Tolima in the early 20th century, points out that this

system was a common practice in many coffee plantations, although it was with

certain variants[26]. The first one, when the farmer received a part of

the plantation- tablón-,

and took care of its collection, profit and washing, to then divide the produce

in half with the owner, who in turn assumed the expenses caused by the weeding

and clearing machines. This included the house to live in that the tablonero acquired, the possibility

to grow crops and to have domestic animals. There were other forms of

agreements. For example, when the batch of coffee was delivered to several

workers, who cared for it, then during the harvest they distributed the grain

collected each day and bought the coffee harvested from the owner at a

conventional local price. The third option was also given,

when the farmer received the land for the sowing of coffee trees until the

first harvest, agreeing a price with the owner for the number of coffee trees

planted, who paid them, and so on make a new arrangement that could be one of

the two variants mentioned above.

In any case, the "head of household" was

directly responsible to the landowner or his managers for issues related to

collection and money lending. The empirical evidence is very limited for making

a demographic analysis of this population, what we can notice is that for a

piece of land with 100,000 coffee trees, it would have been probable to have 40

or 50 families of tabloneros[27]. Very few women were directly responsible to the

administration, although, judging by the evidence, it

was almost always women who took care of the trees in times of tension. Wars

and conflicts led to the victimization of landowners and workers in coffee

zones. Recall that since 1870 the country lived through four civil wars (1876,

1885, 1895 and 1899), the longest and most decisive was the War of the Thousand

Days (1899-1902), various social movements and strikes (1930s), agrarian

reforms (1930s and 1960s), and the bipartisan violence that hit all these

regions (1950s and 1960s). Regardless of the previous phenomena or political

factors, the role of women was always decisive for the maintenance of permanent

family labor, with children and infants; but also of temporary situations, in

the case of recruiting migrant workers from other regions. Viewed from a

socio-labor and functional perspective, domestic work, self-consumption crops

or family farms or gardens, coffee harvesting, domestic animal husbandry and

biological reproduction of family labor typifies the work of tablonera women.

In the first decades of the 20th century,

when there were direct landowners-exporters, production relations supported by

the family nucleus had their golden age. They even allowed that the direct

administration of the landowner did not intervene in the hiring of temporary

labor, and on the contrary the relations of sharecropping were strengthened,

with great autonomy on the side of the tabloneros regarding

the means of production. Then the relations of subordination were patriarchal,

the labor codes were different, and the generosity of the landowner was mixed

with relations of patronage. It was also the golden age of Colombian coffee

cultivation in terms of its traditional production and the end of a dynamic

process that specialized the country in coffee. By 1937,

properties with labor and economic constraints had only one family working and

sharecropping. They represented, according to Dávila

only 1.5%, about 551 tenants, of the rural population of Líbano (Tolima). They were the social and labor base of the well-known " tablón system"

and they were also those who guaranteed not only the expansion of the crop, but

also its care, maintenance and harvesting from the beginning of its

popularization [28].

4. The Role of

Women

The coffee zones of the Central mountain range stand

out for the high immigration produced by the economic perspectives of the

process of expansion of the grain. In this space, the socio-cultural

homogenization should be considered, especially in Antioqueña,

but that converged with elements from the Cundiboyacence highlands, Cauca

and Tolima, among others[29]. The characteristic was the existence of a type of

family with a high level of procreation and certain features of religious puritanism.

However, in the unused border areas the presence of the ecclesiastical

institution is evident, the small property, the tablones, the subsistence crops and the little influence of

general economic crises on demographic phenomena offered the necessary security[30].

In this context, women stand out in their socio-family

environment for their domestic work and the procreation of the family

workforce, but also for the subordination of their role in the private sphere

of the home. However, they are also accused of a certain passivity regarding

the modernizing tendencies of those years, which is why women are singled out

for their religious culture and degree of illiteracy[31]. They were very active in the infinite labor of

domestic work, in a socio-cultural context, where the job of keeping the fire

alight, cooking, serving food and washing the dishes were defined as

exclusively female jobs. To this should be added certain patterns of behavior,

which were clear and defined for women of the era, judging by Manuel Mejía's behavioral manual and behavioral rules for women in

a traditional home[32]. They were customs and practices that mothers usually

did in the company of some daughter or daughter-in-law, in such a way that they

would be transmitted by way of custom.

In an agricultural culture of self-consumption, values around prosperity were different. The abundance of products and food, the number of coffee plantations, domestic animals and, finally, the prosperity of the family farms, determined the quality of life of the family nucleus, but also their participation in the work, as a feeder, collector or chooser. They participate in the production process in different agrarian structures specialized in coffee cultivation, but in a subordinate way. It is obvious that the landowner could also occasionally dispose of her work or even the feeding of temporary staff.

It should be noted that women's labor participation

varied according to the plantations and their eventual needs. For example, at

the beginning of the 20th century, a report by the British consulate

on the state of the coffee trade in Colombia indicates that the collection was

"carried out by women and children," who are "generally given

free food[33]."

Women were the protagonists in the times of coffee collection,

there they were known as the "chapoleras".

The plantation could

occasionally dispose of their work in specific tasks, but also as pickers in

the plantation, urban, state or private thresher, and as a "feeder"

of the temporary staff[34]. On the other hand, in

the peasant household, they were the support of the tablonero for the management of

the assigned coffee plantation. They were coffee collectors, feeders, and helpers in the raising and

feeding of domestic animals - pigs, chickens, turkeys; and they worked on subsistence

crops and the family vegetable gardens.

The evidence on the use of female and child labor in

the face the absence of male personnel was already pointed out. The National

Journal of Agriculture points out that the social conditions of women were

deplorable towards the 1920[35]s. There were those who considered that the cause

was due to their common-law status and because the family responsibility rested

on them. Misery and illness were their burden, not excluding intra-family

violence and oppression from men. The overwork and simultaneity of countless

tasks were their burdens.

In the 1930s the social

situation of women was more critical. Some farmers suggested making compromises

between landowners to "moralize" the plantations. For

example, through the exclusion of workers living in common-law situations, and

the provision of a reasonable time to legitimize unions or to vacate houses[36].

That high degree of exploitation was the same in the urban sector, as we shall

see later.

The above represents the intentions in different decades of landowners and institutions to improve the social conditions of rural women. The scope is unknown. In any case, differences and social responsibilities in the family environments changed and varied considerably inside of them or the same localities.

5. Small and medium properties On the other hand, in the medium and small properties, their work possibly had an additional stimulus, because not only did they have possession of the coffee lots, but also of the land itself. Land and tenure was the guarantee, as a mean of production, to have a large family in areas where the school dropout rate was excessively high at harvest time or where there was simply no such facility (figure 2).

Figure 2. Map of coffee harvests

Source: FNCC

The transformation of the rural sector and the

participation of numerous families in small and medium properties were evident.

Let us remember that around 1932 there were about 150 thousand coffee farms.

Most were small properties of less than ten hectares. Very different from the

5000 farms estimated to have existed sixty years ago[37]. The expansion of coffee from smallholders was

successful, without ignoring the prevalence in some areas of large plantations.

Small landholding was evident in coffee departments. Early as the middle of the

20th century, Guhl points out that 48% of

the national production was on properties that had 5000 trees[38]. But the social and cultural reality of the small

producer was very precarious.

The support of a small owner was his basket and children, or even if he had no land, the agreement with the owner of the coffee plantation. He walked in his feet bare and barely covered in clothing, so he was prone to attacks from intestinal parasites and mosquitoes. In the afternoon, he removed the skin and de-pulped coffee. The pulp remained on the floor attracting mosquitoes, or forming a slimy layer on the floor. Every day they took the coffee out in the sun to dry it or to store it depending on the winter. Every Saturday at dawn they went to the village by

a trail. The coffee farmer grabbed his ruana and cowhide

and headed to the village, cheerful and optimistic. In the village, he unloaded

with an intermediary - banker or developer -, who facilitated money for the

markets while the grain flourished. The custom was to buy tools, clothes and

salt on credit. The peasant did not always have the coffee dry, clean, blown

and without any dirt. Therefore, it was not always bought by the National

Federation of Coffee Growers[39] and he was at the mercy of the intermediary, who

then bought it much cheaper. This was the picture of most poor farmers[40].

Alongside the small coffee-growing plantations,

dozens of newly founded villages in the 19th century also entered the

market with some industrial vigor and became labor suppliers, some related to

the harvesting of grain in the rural sector on coffee farms, and others with

the semi-industrial phase, in coffee threshing machines.

A la par del minifundismo cafetero, decenas de pueblos recién

fundados en el siglo XIX también entraron con cierto vigor industrial y se

convirtieron en ofertantes de mano de obra, alguna relacionada con la

recolección del grano en el sector rural en fincas cafeteras, y otra con la

fase semi-industrial, en las trilladoras de café.

6. Urban sector: Female Pickers

Take the case of the Department of Antioquia, where we can better observe part of this phenomenon. Alejandro López points out that by 1913 in only 50 municipalities there were about thirty million trees[41]. The northern zone of the Department of Tolima, with villages mostly of Antioquian descent, likewise had millions of trees. The Department of Caldas and its municipalities saw the same phenomenon. What is evident in this context is that, along with millions of trees, threshing machines and commercial activities must have flourished. The statistical reports of Monsalve (1927, 271-275) indicate the existence of 42 threshers and 8,142 pulpers in 81 municipalities of Antioquia around 1927[42]. Fredonia and Medellin were the municipalities with the largest number, with a total of 22. In this context, there is an emergence of a salaried and female urban working class.

They were the "pickers", a new modality of workers. It is true that there was a demographic predominance of women with respect to men, which indicates that the predominance of proletarian women was also greater[43]. They constituted the majority of workers with respect to other industries. In the case of Medellín, they represented 34% of the urban working population by 1922[44]. It should be noted that it was a group that had to fulfill minimum requirements regarding its conduct, health, and previous union. The age limits could be between 15 and 50 years, and with it the warning that the use of child labor was not allowed, that it was generalized in the rural sector; but against which they were campaigning for its ban during those years.

It was a group with defined contractual obligations, which was not always in the rural sector, for those first decades of the 20th century. They participated in a labor regime, which had a hierarchical system of administration, which could include immediate bosses, directors, administrators or even representatives of the Local Council, as evidenced in the case of the municipality of Concordia (Antioquia) [45]. The "choosers" also had prohibitions in that regime, which was naturally related to any action or impediment affecting their work day, in addition to practices that could compromise peoples honor and the prohibition of tobacco[46]. We can imagine the potential of this group of workers, when coffee was the main wealth of the municipality with an estimated 1.4 million trees, which allowed a production of between 130 and 150,000 arrobas (12.5 kilograms) of coffee annually[47].

In any case, the level of exploitation to which women were subjected was equally high in the urban-industrial sector, in threshing machines and grain improvement facilities for export. These were the times when socialist ideas began to penetrate more strongly in proletarian sectors, and when the efforts of the Communist Party were oriented to the organization of the female labor force, tied to the urban coffee threshers, and to the demand for improvements in their wages and welfare[48]. Let us remember that in 1936 about 3,500 people worked in the threshing machines, and 85% of the workers were female choosers, working piecewise or for hours[49]. The only exception is the case of the Municipal Thresher of Concordia[50], where the obligation was to comply with eight-hours a day. According to Bergquist, the highest wage of the fastest picker did not reach the level of the average wage that men received for their work in urban industry[51]. The majority earned between one-half and two-thirds of that salary. Eduardo Santa also confirms that in Líbano the strongest unions were those of cobblers, slaughterers and female coffee pickers[52]. Their situation and labor exploitation reached such an extreme that the National Federation of Coffee Growers, through its manager Mariano Ospina Pérez, raised the need to improve the conditions of women, especially in the achievement of an equitable remuneration for their work, and a better deal in the plantations[53].

The circumstances and the different political-social factors tended to the organization of strikes of pickers, movements of tenants and later the episode of the so-called era of The Violence, which had as the coffee zones as their epicenter. It is clear that the characteristics were the expulsion of the family nuclei in potential zones of conflict, generating interregional migrations and "political displacements", or in the opposite case, the coexistence of families and their women with the actors of conflict: self-defense groups, guerrillas, bandits and military personnel.

Finally, by 1970, according to the coffee census, the coffee geography identified 315,000 coffee farms with an area of 4,500,000 hectares, of which 1,000,000 were planted with coffee. In that decade, the technification of coffee farming began, which also brought changes in the labor and economic habits of workers. Approximately 3.5 million people were engaged in cultivation, in addition to 1 million day-laborers who worked temporarily at harvest time. The truth is that coffee had until that moment cemented an authentic national economy and a rural labor culture that did not exist in the 19th century, where women and the family were the main guarantors of labor.

7. Conclusions

The above was a brief explanation of the conditions and mode of labor participation of women and families, where their socio-productive role was also essential. Coffee growing emerged and generated processes that allowed the consolidation of phenomena of agro-industrial exploitation and settlement. Evidence indicates that working conditions were deplorable and wages were low for women and the peasant family nucleus. Although they were characterized by achieving some identity around land tenure, coffee lots and work; during a certain time they were accompanied by the union function of the National Federation of Coffee Growers. Gatherers in the rural sector and choosers in the urban. In short, they were paid workers or low-wage workers, in a context where grain production, oriented to the international market, also represented a certain identity for the national economy and its producers.

The socio-political phenomena also had their impact, especially since they altered women’s habitat and socio-labor sphere, but they also evidenced their politicization or unionization, and consequently their visibility. Women likewise, on a global scale, also became present in the dynamics of modernization and emancipation at the beginning of the 20th century. But in reality, women were not as representative in terms of their status as owners or of having property rights over land, or even in legal relationships, a characteristic of sharecropping relationships. A question should be suggested for future research: What were their functions and changes in the technified coffee production phase? In a scenario where the tradition changed and therefore the type of socio-labor and productive relationships did as well.

Documental sources

Archivo Histórico de Concordia (AHC)

Concordia-Colombia. Decretos, 1942, Resolución N° 11, hoja 1.

Archivo Histórico de Concordia (AHC)

Concordia-Colombia. Municipio de Concordia. Tomo 227, “Fundación Concordia

Monografía”, 1947-1949.

El Cronista,

Ibagué, 4 de mayo, 1912.

Fondo Cultural Cafetero. Don Manuel. Mister Coffee. Tomo 1. Bogotá: s.e, 1989.

Gobernación de Antioquia. “De

trilladora municipal a parque educativo”, Medellín: Gobernación de Antioquia, http://antioquia.gov.co/index.php/prensa/historico/12192-de-trilladora-municipal-a-parque-educativo

(30 de octubre de 2014).

Bibliography

Anuario estadístico del Distrito de

Medellín, 1922. Medellín: Tipografía Bedout,

1923.

Arango Gaviria, Gabriela. 1995. “El proletariado femenino entre

los años 50 y 70. Las mujeres en la historia de Colombia (mujeres y

sociedad)”. En: Las Mujeres en la Historia de Colombia, Tomo III Mujeres y Cultura,

Velásquez Toro, Magdalena (ed.). Bogota: Consejería Presidencial para la

Política Social, Presidencia de la República de Colombia, Grupo Editorial

Norma, 1995.

Arango Gaviria, Gabriela. “Trabajadoras en campos y ciudades:

Colombia y Ecuador”. En: Historia de las

mujeres en España y América Latina. Del siglo XX a los umbrales del XXI,

Isabel Morant (dir.),

Ediciones Cátedra (Ed.), 2006.

Archila Neira, Mauricio. Cultura

e identidad obrera. Colombia 1910-1945. Bogotá: Universidad Nacional de

Colombia, 1992.

Arcila, María. “El caturra y la

familia campesina cafetera, o cambios económicos y familiares entre pequeños

productores de café del municipio de Andes”. (Tesis de grado: Universidad de

Antioquia, 1984).

Bejarano, Jesús, Antonio. “El fin de la economía exportadora y

los orígenes del problema agrario”. Cuadernos

Colombianos, Tomo II, N° 8, (Cuarto Trimestre, 1975).

__________. Ensayos

de historia agraria colombiana. Bogotá: CEREC, 1987.

Bergquist,

Charles. Café y conflicto en Colombia,

1886-1910. La guerra de los mil días: sus antecedentes y consecuencias.

Medellín: Fondo Rotatorio de Publicaciones FAES, 1981. (tr. del inglés por Moisés Melo).

Bergquist,

Charles. “Los trabajadores del sector cafetero y la suerte del movimiento

obrero en Colombia 1920-1940”. En Pasado

y presente de la violencia en Colombia, Gonzalo Sánchez y Ricardo Peñaranda

(compiladores), 111-165. Bogotá: Cerec, 1986.

__________. Los trabajadores

en la historia latinoamericana. Estudios comparativos de Chile, Argentina,

Venezuela y Colombia. Bogotá: Siglo XXI, 1988.

Bonilla, Elssy

y Vélez, Eduardo. Mujer y trabajo en el

sector rural colombiano. Bogotá, 1987.

Botero, Fernando. La industrialización en Antioquia. Medellín: Hombre Nuevo, 2003.

Colombia,

Ministerio de Agricultura y Campillo, Fabiola. Situación y perspectivas de la mujer campesina colombiana. Propuesta de

una política para su incorporación al desarrollo rural. Bogotá: n.d, 1983. (fotocopia).

Chacón Maldonado, Sara Teresa. La presencia de la mujer en el desarrollo de

la zona cafetera colombiana. Bogota: Colegio Mayor de Nuestra Señora del

Rosario, 1990.

Dávila, Carlos. “Autosemblanza

de empresarios agrícolas. Tres reseñas: Santiago Ede,

Rafael Jaramillo Montoya y Medardo Rivas”. Cuadernos

de Agroindustria y Economía Rural, N°

10 (Primer Semestre, 1983): 9-26.

Dávila, Josué. “Informe sobre el

municipio del Líbano”. En: Anuario

Estadístico del Tolima. Ibagué: Contraloría del Tolima, 1937.

Deere, Carmen Diana y León de Leal,

Magdalena. Women in Andean agriculture: peasant production and rural wage

employment in Colombia and Peru. Geneva:

International Labour Office, 1982.

García, Antonio. Geografía

económica de Caldas. Bogotá: Banco de la República, 1978, 2da. ed.

García, Claudia. “Honor y mujer en el

homicidio”. (Trabajo de grado optativo al título de Licenciado en Ciencias

Sociales, Universidad del Tolima, 1992).

García, Mary. Migración laboral femenina en Colombia. Bogotá: Ministerio de

trabajo y Seguridad Social, Senalde, 1979. Serie

Migraciones Laborales N° 16.

Garzón Castro, Martha Isabel. Mujeres trabajadoras del café. Bogotá:

Ministerio de Cultura, 2002.

Grossman, Shana

y Leandro Harold. “La mujer en el proceso productivo del café. Los casos de

Costa Rica y Brasil”. Ciencias sociales,

N° 45-46: (1986): 143-154. http://revistacienciassociales.ucr.ac.cr/wp-content/revistas/45-46/grossman.pdf

(30 de octubre de 2014).

Escobar Belalcázar, Carlos Arnulfo. Historia furtiva: mujer y conflictos

laborales, las escogedoras de café en el Antiguo Caldas (1930-1940). Pereira: Universidad Tecnológica de

Pereira, 1995.

Fajardo, Darío. Violencia y desarrollo. Transformaciones sociales en tres regiones

cafeteras del Tolima, 1936-1970. Bogotá: Suramericana, 1979.

Federación Nacional de Cafeteros.

1934. “Informe rendido por el Gerente Mariano Ospina Pérez, Gerente de la

Federación Nacional de Cafeteros al VI Congreso Nacional de Cafeteros”. Pasto. Informe leído en el VI

Congreso Nacional de Cafetero en 1934.

Gaitán,

Gloria, Colombia. La lucha por la tierra en la década del treinta, génesis

de la organización sindical campesina, Bogotá, Tercer Mundo, 1976.

García, Antonio. Geografía

económica de Caldas. Bogotá: Banco de la República, 1978.

García,

Mary. Migración laboral femenina en

Colombia. Bogotá: Ministerio de trabajo y Seguridad Social, Senalde, 1979. Serie Migraciones Laborales N.° 16.

Guhl,

Ernesto. “El aspecto económico-social del cultivo de café en Antioquia”, Revista colombiana de antropología. Vol.

1, N° 1 (1953): 198-257.

Jaramillo Arango, Euclides. Un extraño diccionario: el castellano en las

gentes del Quindío, especialmente en lo relacionado con el café. 2a. ed. Armenia: Editor Comité

Departamental de Cafeteros del Quindío, 1998.

Kalmanovitz, Salomón. “El régimen

agrario durante el siglo XIX en Colombia”. En: Manual de Historia de Colombia. Vol. 2, Bogotá: Editores Procultura SA, 1984.

LeGrand, Catherine. Colonización y protesta campesina en

Colombia (1850-1950). Bogotá: Ediciones Universidad

Nacional de Colombia, 1988. (Traducción del Ingles por Hernando Valencia).

León de Leal, Magdalena. Mujer y capitalismo agrario, estudio de

cuatro regiones colombianas. Bogotá: Asociación Colombiana para el Estudio

de la Población – ACEP, 1980.

__________. La Mujer y el desarrollo en Colombia. Bogotá: ACEP (Asociación

Colombiana para el estudio de la población), 1997.

Londoño, Carlos Mario. Economía agraria colombiana. Madrid:

Ediciones RIALP, S.A, 1965.

López, Alejandro. Escritos escogidos. Bogotá: Editorial Andes. Serie Biblioteca

Básica de Colombia, 1976.

Machado,

Absalón y otros. El agro en el desarrollo histórico colombiano,

Ensayos de Economía Política. Bogotá: Punta de Lanza, Seminario

Nacional de Desarrollo Rural, ed., 1977.

Maya Lema, Carlos Mario. De la

"Comia" a Concordia. Medellín: Imprenta

Departamental de Antioquia, 2005.

Medrano, Diana. “La mujer en la región

cafetera del suroeste antioqueño”. En: Mujer

y capitalismo agrario. Bogotá: Asociación Colombiana para el estudio de la

población, Colombia, 1980.

__________. Mujer campesina y organización rural en Colombia: tres estudios de caso.

Bogotá: Fondo Editorial Cerec-Universidad de los

Andes-Departamento de Antropología, 1988.

Meertens,

Donny. “La aparcería en Colombia: formas, condiciones

e incidencia actual”. Cuadernos de

agroindustria y economía rural. Bogotá, N° 14-15 (I-II semestre,

1995):11-62.

__________. Tierra, violencia y género. Hombres y mujeres en la historia rural de

Colombia 1930-1990. Holanda: Editorial de la Universidad Católica de Nijmegen-Katholieke Universiteit,

1997.

McGreevey,

William Paul. Historia económica de

Colombia, 1845-1930. Bogotá: Tercer Mundo, 1982. 3ra. Ed. (Traductor Haroldo Calvo).

Molina, Gerardo. Las ideas

socialistas en Colombia. Bogotá: Editorial Tercer Mundo, 1987.

Monsalve, Diego. Colombia Cafetera. Bogotá: Artes Gráficas SA, 1927.

Muñoz, Cecilia. El niño trabajador migrante en Colombia. Bogotá: Ministerio de

Trabajo y Seguridad Social, Senalde, 1980. Serie

Migraciones Laborales. N.° 18.

Ordoñez, Myriam. Población y familia rural en Colombia. Bogotá: Pontificia Universidad

Javeriana, 1986.

Palacios, Marco. El café en

Colombia 1850-1970. Una historia económica, social y política. México: El

Colegio de México, 2009. 4a edición.

París, Gonzalo. Geografía económica de Colombia. Tolima. Tomo 7. Bogotá: Editorial

Santafé, 1946.

Parsons,

James. La colonización antioquena en el

occidente de Colombia. Bogotá: Banco de la

Republica, El Ancora Editores, 1997.

Poveda Ramos, Gabriel. Historia económica de Antioquia. Medellín:

Autores Antioqueños, 1988.

Ramírez

Bacca, Renzo. “Formación de una hacienda cafetera: mecanismos de organización

empresarial y relaciones administrativo-laborales. El caso de La Aurora

(Líbano, Colombia), 1882-1907”. Cuadernos

de desarrollo rural, N° 42

(1999): 83-116.

__________. Colonización del Líbano. De la distribución de baldíos a la formación

de una región cafetera, 1849-1907. Serie

Cuadernos de Trabajo de la Facultad de Ciencias Humanas, 23, Bogotá: Universidad

Nacional de Colombia, 2000.

__________. “Trabajo, familia y hacienda, Líbano-Tolima,

1923-1980. Régimen laboral-familiar en el sistema de hacienda cafetera en

Colombia”. Utopías Siglo XXI, vol. 3, N° 11 (2005): 89-98.

__________.

“Formas organizacionales y agentes laborales en la caficultura tradicional

colombiana, 1882-1972”. En: Vías y escenarios de la transformación laboral: aproximaciones

teóricas y resultados de investigación. Bogotá: Editorial Universidad del Rosario, 2008.

__________.

Historia

laboral de una hacienda cafetera. La Aurora, 1882-1982. Medellín,

La Carreta Editores E.U., 2008.

__________. “Colonización y enganche en zonas cafeteras. Los casos de

Tapachula (Soconusco-México) y Líbano (Tolima-Colombia), 1849-1939”. En: Miradas

de contraste. Estudios comparados sobre Colombia y México. México:

Universidad Autónoma de San Luis Potosí-Universidad Nacional de Colombia, sede

Medellín, Miguel Ángel Porrúa Editor, 2009.

__________.

“Estudios e historiografía del café en Colombia, 1970-2008. Una revisión

crítica”. Cuadernos de Desarrollo Rural,

N° 64 (2010): 13-29.

__________. “Clase obrera urbana en la

industria del café. Escogedoras, trilladoras y régimen laboral en Antioquia,

1910-1942”, Desarrollo y Sociedad, N°

66 (2011): 43-69.

Ramírez

Bacca, Renzo e Tobasura

Acuña, Isaías. “Migración boyacense en la cordillera Central, 1876-1945. Del

altiplano cundiboyacense a los espacios de homogenización antioqueña”. Boletín

del Instituto Francés de Estudios Andinos, Vol. 33 N° 2 (2004): 225-253.

Revista

Nacional de Agricultura, (RNA), 1920.

Rodríguez Giraldo, Viviana. “Contexto

rural caficultor en Colombia: consideraciones desde un enfoque de género”. La manzana de la discordia. Vol. 4, N° 1

(enero- junio, 2009): 53-62.

Rodríguez, V., & Yepez, M. Hombres y

Mujeres del proyecto Cafés Especiales. Cali: Cencoa,

2002.

Rodríguez Valencia, Lina María. “La

riqueza invisible: familia y mujer en tres localidades cafeteras”. (Tesis de

magister en sociología, Universidad del Valle, 2013).

Saether, Steinar. “Café, conflicto y corporativismo. Una hipótesis

sobre la creación de la Federación Nacional de Cafeteros”, Anuario

Colombiano de Historia y de la Cultura, núm. 26 (1999): 134-163, http://www.bdigital.unal.edu.co/20608/1/16770-52549-1-PB.pdf (30 de octubre de 2014).

Santa, Eduardo. Recuerdos de mi aldea, perfiles de un pueblo y de una época.

Bogotá: Ediciones Kelly, 1990.

__________. Arrieros y fundadores. Líbano: Alcaldía Popular del Líbano, 1997.

__________. La Colonización

Antioqueña, una empresa de caminos. Bogotá: TM Editores, 1993.

Scott, Joan W. “El género: una

categoría útil para el análisis histórico”. En: El género: la construcción cultural de la diferencia sexual. México:

PUEG, 1996. http://www.inau.gub.uy/biblioteca/scott.pdf (30 de octubre de 2014).

Spencer S. Dickson. “Informe sobre el

estado actual del comercio cafetero en Colombia, septiembre 11 de 1903”. Anuario Colombiano de Historia Social y de

la Cultura, (1976): 101-106.

Stolcke, Verene. “The exploitation of Family

Morality. Labors Sistems and Family Structure on on Säo Paulo Plantations,

1850–1980”. En: Kinship

Ideology and Practice in Latin America, 1984.

Stolcke, Verena. Coffee

Planters, Workers and Wives: Class Conflict and Gender Relations on Säo Paulo

Plantations, 1850–1980. New York: St. Martin's. Press, 1988.

Suárez Quintero, Johana Paola. “Un álbum,

una historia, una identidad: Estudio sobre la construcción cultural de la

identidad de la mujer cafetera en Marquetalia. Caldas”. (Tesis de Magíster, Universidad Nacional de

Colombia Sede Bogotá: 2011).

Tovar, Hermes. Que nos tengan en

cuenta. Colonos, empresarios y aldeas: Colombia 1800-1900. Bogotá: Tercer

Mundo Editores, 1995.

Valencia Llano, Albeiro. Vida cotidiana y

desarrollo regional en la colonización antioqueña. Manizales: Universidad

de Caldas, 1996.

Velásquez

Toro, Magdalena (ed.). Las mujeres en la

historia de Colombia. Tomos I-III. Bogotá: Consejería Presidencial para la

Política Social, Presidencia de la República, Editorial Norma, 1995.

Villareal Méndez, Norma. “Movimiento

de mujeres y participación política en Colombia, 1930-1991”. En Historia, género y política: movimiento de

mujeres y participación política en Colombia, 1930-1991, 57-78. Barcelona:

Seminario Interdisciplinar Mujeres y Sociedad, 1994.

Zamosc, León. La cuestión agraria y el movimiento campesino en Colombia. Ginebra:

Instituto de

Investigaciones de las Naciones Unidas para el Desarrollo Social,

1987.

To cite this article:

Renzo Ramírez Bacca, “Women in Traditional Colombian Coffee Growing, 1910

– 1970.”, Historia

y Memoria N°10 (January-June, 2015): 43-73.