María del Rosario García[1]

Universidad

del Rosario

Reception: 05/12/2014

Evaluation: 28/01/2015

Approval: 28/05/2015

Research and

Innovation Article.

Abstract

This article

comprises of a tour of the library of Brother Cristóbal de Torres, a prolific

reader in 17th century New Granada, Archbishop of Santafé de Bogotá and the

founder of Colegio Mayor de Nuestra Señora del

Rosario. The nature of this library is analyzed in comparison with others from

the epoch, as well as some aspects related to the diffusion of knowledge in

Spain and America, through the analysis of the texts donated to Colegio Mayor del Rosario by the archbishop. Likewise, this article

presents some conclusions regarding the conditions of education in 17th century

New Granada.

Key Words: History of the book, History of

education, 17th century, Diffusion of knowledge.

Bibliotecas de la Nueva

Granada del siglo XVII: La biblioteca de Fray Cristobal de Torres en el Colegio

Mayor de Nuestra Señora del Rosario*

Resumen

El presente artículo es un recorrido por la biblioteca de Fray Cristóbal de

Torres, lector del siglo XVII en la Nueva Granada, Arzobispo de Santafé de

Bogotá y fundador del Colegio Mayor de Nuestra Señora del Rosario. En él se

analiza la naturaleza de dicha biblioteca en comparación con otras de la época,

así como aspectos relacionados con la circulación de saberes en España y

América a partir del análisis de los textos donados por el Arzobispo al Colegio

Mayor del Rosario. De igual manera, el artículo permite sacar conclusiones

sobre las condiciones de la educación en la Nueva Granada del siglo XVII.

Palabras clave: Historia del libro,

Historia de la educación, siglo XVII, circulación de saberes.

Bibliothèques de la Nouvelle Grenade du XVIIe

siècle: La bibliothèque de Fray Cristóbal de Torres dans le Colegio Mayor de

Nuestra Señora del Rosario

Résumé

Cet article fait

un parcours par la bibliothèque de Fray Cristóbal de Torres, lecteur en

Nouvelle Grenade du XVIIe siècle, Archevêque de Santafé de Bogota et

fondateur du Colegio Mayor de Nuestra Señora del Rosario. Le texte analyse les

traits de cette bibliothèque en tissant une comparaison avec d’autres de la

même époque, ainsi que certains aspects de la circulation de savoirs en Espagne

et en Amérique à partir de l’analyse des textes donnés par l’Archevêque au

Colegio Mayor del Rosario. L’article permet de mieux comprendre la situation de

l’éducation dans la Nouvelle Grenade du XVIIe siècle.

Mots clés: Histoire du livre, Histoire de l’éducation,

XVIIe siècle, circulation de savoirs

1. Introduction

The history of the book in Colombia has been strongly

influenced by the history of mindsets. A significant part of the few studies on

this subject are represented, leaving aside textual studies, by the catalogs of

private libraries[2], notarial studies, histories of the printing press[3] or are devoted to the history of literature, more

focused on the production of books than on their reception[4]. In turn, this limited range of topics is directly

related to the fact that studies on the history of reading are practically

non-existent. On the other hand, most of the studies on the book in the

colonial period have been devoted to the study of books in the eighteenth

century and their relation to the arrival of Enlightenment ideas in New

Granada. This tendency is related to the long-held practice in traditional

Colombian historiography of taking from the colonial past only what has been

conceived as a precursor of the Independence. This also explains why the 16th

and 17th centuries are dealt with very superficially in the histories as part

of a homogeneous and uninteresting colonial past.

Within this approach is, for example, the text Recepción y difusión de textos

Ilustrados[5], a compilation of articles and papers of the II

European Congress of Latin Americanists. The text, although it contains

valuable articles on the cultural field and the history of the book in the

eighteenth century that constitute interesting contributions to the cultural

history of the period, does not contain any article that refers, in a

tangential way, to the subject of the practices of reading and readers; its

interest is mainly focused on texts or ideas and their dissemination. The same

can be said of the texts compiled by Eduardo Santa in El libro en Colombia[6], which also includes a series of articles on the

history of printing. Similarly, the text of Pilar Jaramillo La producción intelectual de

los Rosaristas 1700-1799[7] is a bibliographic catalog, which contains an

introduction with interesting data on the uses of books by intellectuals and

the circulation of books in America in the eighteenth century. In fact, the

historian points out how, in the second half of the eighteenth century, a new

generation of intellectuals emerged, characterized by a more intense use of

books; because of a growing interest in the particular possession of them.

Their scarcity sometimes led to high sums of money being paid for them and to a

significant circulation of books, borrowed or given, among the small

enlightened creole elite. Similarly, Jaramillo draws attention to the controls

on the book trade and on the production of printed documents imposed by the

Inquisition.

These histories of books suffer from one or more of

the limitations that Chartier[8] points out when setting out his account of the

history of the book in France, which is explained by the strong influence

exerted by the 'history of mentalities' on these authors. Most library cataloging

works are used as sources for other works, which although useful in many cases,

does not take into account the 'ways' of accessing and using books; the forms

of appropriation and invention of meanings; the difference between books and

text.

An important text in the Latin American context, for

having questioned a series of already naturalized beliefs in the history of the

conquest and colonization, is that of Irving Leonard, Los libros del

conquistador (The Books of the

Conquistador) [9]. The book aims to "first, explore the possible

influence of a popular form of literature on the minds, behavior and acts of

its Spanish contemporaries in the sixteenth century; second, to describe the

mechanism of the book trade in the New World; and third, to prove the universal

diffusion of the Spanish literary culture through the extensive Hispanic world

of that time.[10]” The fundamental contribution of Leonard's book,

besides establishing an interesting articulation between the diffusion and

commercialization of books, has been to break with the belief, propitiated by

the "black legend"[11], that Spain had kept its American colonies in a kind

of intellectual obscurantism. Leonard's study shows how there was a large book

trade between the metropolis and its colonies, so that the cultural distance

was not so great as had been thought.

Maria Teresa Cristina's article on literature in the

conquest and the colony in New Granada, published in La Nueva Historia de Colombia (The New History of Colombia), although it focused on

the production of books, Cristina relies on research such as that of Irving

Leonard , Rivas Sacconi and Torre Revello, which demonstrates how there was a

wide circulation of books among the literate minority of Spanish America and

how these books were not restricted to those of a purely religious and

moralizing nature. Indeed, in New Granada, even considering the smallness of the

society (which cannot be compared with those of Peru or New Spain), all kinds

of books circulated, even those prohibited, as in the case of an annotated

example by Bartholomeus Vespucius, Oratio

de laudibus astrologiae, belonging to Brother Cristobal de Torres, and

those of a literary nature such as the 103 copies of the first edition of El Quijote that arrived in Cartagena in

1605, the same year as its publication[12]. A good example of this is the catalog of the 1060

volume library of Don Fernando de Castro y Vargas (a contemporary and

acquaintance of Brother Cristóbal de Torres) published by Guillermo Hernández

de Alba and commented on by Rafael Martínez Briceño[13], which shows a great variety of subjects, ranging

from the classics to contemporary literature (Lope de Vega, Góngora, Quevedo,

Tirso de Molina, Cervantes, among others).

The second part of the text by Renán Silva Los ilustrados de Nueva

Granada 1760-1808. Genealogía de una comunidad de interpretación[14], should also be highlighted, dedicated in its entirety to books, their

trade and circulation; libraries, readings and readers, and writing, work and

the public. Although the book is focused on the eighteenth century, Silva makes

a short but interesting analysis of the trade and circulation of books in

colonial society, analyzing various inventories of seventeenth-century

libraries. Similarly, it includes a chapter on the new practices of reading in

the eighteenth century, "more private and closer to the daily activities

of the subject ..., and at the same time, a type of reading ordered and built

in relation to more immediate objects"[15]. Its inclusion is important because it constitutes a breaking

away from the approaches that have traditionally been given to the history of

books, education and culture in Colombia, being one of the few studies that establish

links between the history of reading and the uses of books and the educational

field.

Finally,

it is necessary to cite the degree project of Catalina Muñoz Rojas, Una historia de la lectura

en la Nueva Granada: el caso de Juan Fernández de Sotomayor[16]. This research studies the case of a parish priest of

Mompox at the end of the colony (1808-1819) who wrote the Catecismo Político o

Instrucción Popular, which

refutes the legitimacy of the conquest of America and defends the right of

Americans to govern themselves. The author asks how

Juan Fernández de Sotomayor elaborated his speech and from where he obtained

the concepts that formed it. To answer these questions the researcher focuses

on the ways in which the pastor received, appropriated and used his readings,

giving them an interpretation and meaning of their own. Although the work

refers to a different historical moment from the one that is dealt with in this

article, its approach is very valuable in that it focuses on the problem of the

reception and appropriation through analysis of the writings of the subject,

constituting itself as one of the few works that have been done in the field of

the history of reading.

2. The library of Brother Cristóbal de Torres in Santafé de Bogotá

The library of Brother Cristóbal de Torres is part of

the collection of old books of the Historical Archive of the Colegio Mayor de Nuestra Señora del Rosario (AHCMNSR, by its acronym in Spanish)[17]. It is a collection of books belonging to the

Archbishop of Santafé and the founder of the Colegio Mayor, which were taken

out of open circulation and included in the archive at the beginning of the

19th century. The catalog of the library of Brother Cristóbal de Torres was

elaborated from the revision of the books of the Historical Archive that were

published before 1653, the year in which Brother Cristóbal died[18]. For the preparation of the catalog, more than 700

books were revised, of which only 175 were selected, corresponding to those

marked as belonging to Brother Cristóbal de Torres, either because they are

signed with his name or because they say they belong to the Archbishop of

Santafé. There are some volumes that for their subject and date of publication

could have belonged to the founder; some of them could have been marked but

they lack the page of the cover where Brother Cristóbal used to mark his books.

These were classified as doubtful and did not enter into the analysis referred

to in this article. The themes established in the catalog are in accordance

with the classification of the Historical Archive of the Colegio Mayor de Nuestra Señora del Rosario.

The catalog of 175 books is the primary source on

which this article is based. It should be noted that this set of books,

belonging to the founder of the Universidad del Rosario, does not constitute a source to determine the

cultural heritage of this subject, since they are simply the books that Brother

Cristóbal donated to the Colegio Mayor de Nuestra

Señora del Rosario. His personal library

may contain other books, of which we do not know their fate. What we can know

for sure is that Brother Cristóbal had access to, and read, a number of works

that are not included in this catalog. These readings are known through the

books he cited in his writings and which differ from those donated to the Colegio Mayor del Rosario[19]. We find in his writings an infinity of quotations

and references not only to Saint Thomas and the Scriptures, but also to a great

variety of holy theologians, philosophers, Latin poets, and exegetes. Augustine,

Judah Leon Abravanel, Bernardo,

Dionisious, Philo Judeaus, Damiano, Martial, Aristotle, Cajetan, Santes

Pagnino, Jansen, Saint Jerome, Bede, Hilary, John of Damascus, Andreas of

Crete, Ambrose, Procopius, Theodoret of Cyrus, among others, are examples of

the multiple references cited only in the first hundred pages of Cuna Mystica. Most of these authors are

not found in the catalog of books signed by Brother Cristobal and are part of

the catalog studied, which suggests that the books he donated are the ones the

Dominican considered useful for the College.

The books in the catalog are those found in the

Historical Archive of the Universidad del Rosario. It

is not known whether Brother Cristóbal had other books in Santafé de Bogotá.

However, the catalog of this library is important because it can shed light on

what this subject considered important in terms of the knowledge of the time

and what was the knowledge that Brother Cristobal considered important for the

study of law, theology and medicine.

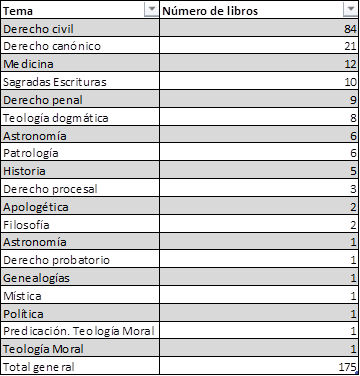

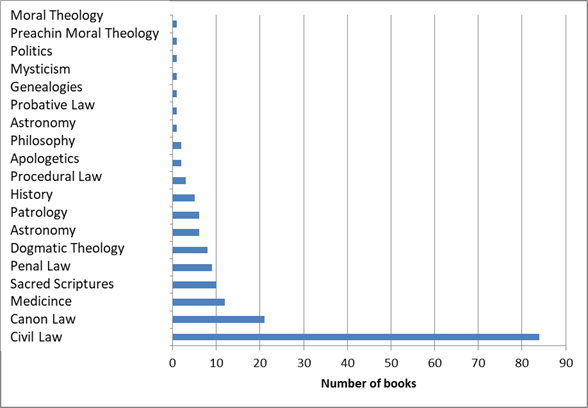

In contrast to what Renán Silva[20] says about seventeenth-century libraries being made

up mostly of theological texts and religious preaching, the library that was

preserved by Brother Cristobal de Torres in the Colegio Mayor de Nuestra Señora del Rosario contained 67.3% law books, within which 81% corresponded to civil,

criminal and procedural law and only 19% to canon law. The other books covered

various subjects such as theology, sacred scriptures, patrology, astronomy,

medicine, history, philosophy, and politics, without the strictly religious

books predominating[21]. The latter constitute 16.8% of the total of the

books of the library, that is to say, less than the set of other non-religious

subjects other than law.

Now, this statement must be qualified by the fact that

in the seventeenth century the limits between what can be considered a

religious book and one that is not can be quite diffuse. In fact, the

boundaries between the various disciplines were neither clear nor blunt, as

noted by F. Copleston when referring to Francisco Suarez (1548-1617), one of

the greatest representatives of the so-called Spanish neo-scholasticism:

[…] In his preface to 'De legibus ac Deo legislatore' (1612)

Suarez observes that no one should be surprised to find a professional

theologian embarking on a discussion of the law. The theologian contemplates

God not only as God is in Himself, but also as the ultimate end of man. This

means that the theologian is interested in the path to salvation. Now,

salvation is achieved through free acts and moral rectitude; and moral

rectitude depends to a great extent on the law, considered as the norm of human

acts. Theology, then, must comprehend the study of law[...] It may be objected

that the theologian, even if he legitimately attends to divine law, should refrain from dealing with human law. But

every law ultimately derives its authority from God; and it is justified that

the theologian should deal with all types of law […][22].

For Suárez, there was no definite boundary between

theology and law. However, the fact that he has been preoccupied with

explaining in the preface of his book why a theologian can and must deal with

matters of civil law also shows that as early as the seventeenth century,

Spanish had begun to form the disciplinary boundaries so characteristic of

modernity, and that theology had already lost some of its power over philosophy

and other disciplines. The preface of Suarez, despite defending the diffuse

boundaries between theology and law, allows the civil law books to be

considered as non-religious books in the strictest sense, since these limits

were beginning to be established.

In the case of other libraries contemporaneous with

that of Brother Cristóbal, such as that of Don Fernando de Castro y Vargas, we

can find differences that are related to the fact that the library of Brother Cristobal

de Torres that we are analyzing in this article, was

probably not the entirety of his personal library, as already noted. Don

Fernando de Castro y Vargas held the office of priest of the Cathedral of

Santafé as from 1648, when Brother Cristobal de Torres acted as Archbishop in

that same cathedral. He was a contemporary of another recognized scholar, Lucas

Fernandez de Piedrahita, who held the position of canon in the same cathedral,

and of whom it is known, possessed an important library. Another contemporary

of the ecclesiastics already mentioned was the poet Hernando Domínguez Camargo,

a "native of Santa Fe de Bogotá, who had made the stylistic technique of

Góngora his own and composed the poem of the life of St. Ignatius of Loyola in

robust octaves" and also possessed an important library of which we only

know that it was bequeathed to the Jesuits[23].

Most of the 1060 volumes of the Castro y Vargas library

were works of theology, rules, biblical matters, and other religious topics[24]. As well as in the library that Brother Cristóbal

donated to the Colegio del Rosario, almost all the important authors of theology from Saint

Thomas to Suarez, including Domingo de Soto, Bañez and Cajetan, are represented

in his library. Classical, Greek and Roman letters abound in his library, as

well as various texts of the course of arts such as rhetoric, parnassus, grammar and lexicons[25]. There are

also 58 manuscript books: "matters that the said doctor heard; handbooks

from grammar, rhetoric, arts and theology. From grammar to theology, there are fifty-eight

books to hand[26]." That is to say, the famous "weighty tomes"

were part of his library that the students wrote from the dictatio, and that, surely, correspond to the courses that Castro y

Vargas himself "heard" in his time as a student.

Some of the classical authors of his library are: Caesar,

Valerius, Cato, Juvenal, Persio, Martial, Horacio, Lucan, Virgil, Plutarch,

Terence, Tibullus, Cicero, Xenophon, Valerius Maximus, Seneca, Prudentius,

Ovid, Isocrates, Herodias, Ausonius, Titus Livius, Aristotle, Diogenes,

Donatus, Sallust, Pliny, Valerius Flaco, Catullus, Lucanus, Flavian Josephus,

Suetonius, Juventius, Flaminius, Quintus Curtius, Terence, Aesop, and others. From the contemporary literary authors can be

enumerated Cervantes, Tirso de Molina, Lope de Vega, Quevedo, Villamediana,

Garcilaso de la Vega, Góngora, Luis Carrillo and Sotomayor, thus verifying the

rapid diffusion that these authors had in America. Among the scientific books are the Tractatus de Sphaera

(On the Sphere of the World) and Ephemerides by Sacrobosco, the Repertorio de los tiempos by Rodrigo Zamorano, the works of

mathematics and natural philosophy of Pérez de Moya, the Tratado de navegación by García de Céspedes and a treatise on agriculture,

among others. There is also Dante, Torcuato Tasso, Sannazaro, Policiano, Mateo

Vegio and Paulo Manucio representing the Italian letters. Two books of the

library are cataloged in the Índice as prohibited: a work of Erasmus not specified by the

scribe who made the inventory and one Tratado de los planetas, whose author is not mentioned[27].

Unlike the library of Brother Cristóbal, where there

is only one work of an American author, in the library of Castro y Vargas can

be found at least 15 works written in America, some of which were published in

Mexico[28].

According to the analysis of the catalog of the

library of Castro y Vargas made by Renan Silva[29], 54% of the books are on theology, 23% on letters and

humanities (books on the Latin and Greek classics, grammar), 8% on law, 6% on

philosophy and 8% that Silva catalogs as 'various'. In this case it is the

personal library of the canon, composed of more than 1000 volumes that appear

in the notarial inventory made in 1665 and in which the books of law, for

example, constitute a minimum percentage, the most important being theology and

letters and humanities. The case of Castro y Vargas is that of a subject whose

"profile" was more of a "scholar than enthusiast of the “summae"", as Silva affirms[30]. Contrary to this, the library of another

contemporary, the oidor Gabriel Alvarez de Velasco y Zorrilla, contains a large

presence of books of theology and humanities, but can be cataloged, according

to Silva[31], as a specialized library of a professional jurist.

As for the case of the library in question, the small

number of religious books does not mean that Brother Cristobal disdained the

study of religious subjects. On the contrary, the basis of all knowledge,

necessary to study in any faculty, was centered on the verses of Saint Thomas:

We order that no one can in the Colegio

hear any other faculty, without having first heard the verses of Saint Thomas,

for many reasons. The first is because it is not fair for them to hear the

theology of Saint Thomas, without first being founded on the verses of Saint

Thomas. The second, because medicine also needs this

foundation. The third is that laws and canons cannot be consummated

without this prevention, as we are taught by logical truths; and without these

fundaments, they are not consummately canonists, nor legists and without them,

the teachers of the canons and laws are remarkably enhanced, as experience

shows; and our desire is, to leave the college famous canonists and lawyers[...][32]

The predominance of law books can be explained,

rather, in the light of the cultural conditions of seventeenth-century Spain,

that is, it is related to the proliferation of law studies and lawyers in the

peninsula and to the fact that the law was considered in the Spain of the time

as the best employment option for impoverished Spaniards. Brother Cristóbal

sought to offer a possibility of employment to Spaniards and the lay creoles

and secular clergy of New Granada through the founding of the Colegio Mayor, as expressed in

several of his letters. One of them is the letter of protest by Brother

Cristóbal de Torres against the Dominican priests who wanted to appropriate the

Colegio. There he explains the reasons why he wanted to revoke the appointment

of the Dominican Rector and Vice Rector, stating, among other reasons, that

"they wanted to make a house of religion, which according to the

foundation and license of His Majesty was for secular schoolboys, wanting to

destroy our intent and deliberate will so to the universal detriment of the

common good of all this Kingdom."[33] Hence the insistence that the Colegio Mayor was

directed to the laity and the importance that Brother Cristóbal granted to the

Faculties of Law and Medicine. On the other hand, it is very probable that Brother

Cristóbal made frequent use of these books of law during the exercise of his Archbishopric

for the various lawsuits that he had, including that of the Dominicans. In

fact, writes Brother Cristobal in one of his letters: "... it seems to us

very certain to have seen very serious authors who knowingly assure us that we

can revoke that donation ...” [34].

It is not surprising then, that most of the books

donated to the Colegio Mayor del Rosario, and owned by

the founder, were books of law. The medical books, 11 in all, constitute the

third most important group, for the same reasons, that is, because of the

importance that Brother Cristóbal granted to the teaching of medicine in the

New Kingdom of Granada.

It should be noted, however, that the faculty which

functioned the most consistently from the beginning was that of theology, and there

were very few graduates in law and medicine during the seventeenth century.

This may indicate that in New Granada, unlike Spain, the office of lawyer was

still not considered a safe alternative for survival and that theology was

still considered as the highest and most prestigious knowledge. In addition, it

must be taken into account that most of the public offices were occupied by

Spanish lawyers, appointed in Spain, a circumstance that may also explain the

lack of legal studies in New Granada. It is also worth mentioning that it was

precisely this impossibility of access to public offices that generated, a

century and a half later, an important part of the creole discontent that led

to the independence movement. Brother Cristóbal wanted to deliver to New

Granada an educational project that still could not be fully applied, given not

only the cultural differences (the primacy of theology, for example), but also

political (the impossibility of Spanish Americans to access public offices).

3. Circulation of knowledge

The books of law and medicine of the library donated

by Brother Cristobal de Torres to the Colegio Mayor de Nuestra

Señora del Rosario are a good example of the kind of knowledge that circulated in the

peninsula and which was transmitted to the students of these faculties. In the

case of law books, the primacy of civil law (79 books) indicates the very

strong emphasis in Brother Cristóbal's intention to educate subjects for public

administration which, as already stated, constituted the main source of

employment at the time in Spain and in America, after the crisis of the encomienda, with the qualifications

already noted. Civil law was then fundamental knowledge, and within this stand

out the books of great jurists such as Bartolus de Saxoferrato (1313-1357) [35], Italian jurist, professor at the University of

Peruggia and one of the great commentators on the code of Justinian. He is

classified as a post-glossator or 'commentista',

to differentiate him from the glossators of the 11th to 13th

centuries, who made the reconstruction and classification of the Corpus Iuris Civilis by Justinian (Digesto Vetus, Digesto Novus, Digesto Infortiatum)[36]. The glossators made innumerable annotations to the Digesto, but at the same time they were very

attached to the literal interpretation of the code, although many of the laws

of Justinian (6th century) were already obsolete. The importance of

Bartolus de Saxoferrato is that he was the first jurist who tried to reform the

law to fit the new historical conditions and not force the facts to fit the

letter of the law as did his predecessors[37].

Another important author of the catalog is Jason of

Mayno Mediolanensis (1435-1519), Italian jurist, professor of the Universities

of Padua, Pisa and Pavia. Commentator of the gloss, he is considered by some as

the last jurist of the school of Saxoferrato. Among his works are Comentarios a todo el Digesto, Código y Usus feudales. Brother Cristóbal left

several volumes of this author in the library (see annexed catalog), some of them with

annotations.

Among the jurists that appear most prolifically in the

library of Brother Cristóbal de Torres are Ubaldus Perusinus Baldus (1327-1400) [38], Italian jurist, pupil of Saxoferrato; Jacobus

Menochius (1532-1607); Sebastianus Naebius Lipsiensis (1563-1643); Pablo de

Castro, who along with Jason de Mayno was one of the great "bartolistas", as the followers of

Bartolus de Saxoferrato and Baldus were called, who have been accused of

abusing the principle of authority in their writings[39]. It should be noted that the principle of authority

was the method that was used in the Middle Ages and

was still used in the fifteenth, sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. It meant

that in order to defend an argument it was considered sufficient to resort to

the opinion of a recognized authority. Bartholomeus Socinus Senensis

(1436-1507), of the same school is also found, but who was more measured in his

citations, according to Carpintero[40], and Iacobus Cuiacus, I.C. (1522-1590), all recognized

jurists. These same books were those that were studied in the faculties of law

of Spain and France and they circulated throughout Europe. All these books were

written in Latin, which in the seventeenth century remained the language of

knowledge and they were published mostly in Lyon (33), Frankfurt (15), Turin

(11) and Venice (8), where some of the most prolific print shops were to be

found (see annexed catalog).

The second largest

group of books after those of civil law are those of canon law (21 in total),

also explainable because canon law was indispensable for the articulation of

the Church with the State, especially "in a setting like that offered by

the Royal Patronage of the Indies, in which, from the administrative point of

view, the Church was subject to the State.[41]" Canon law included all the norms and legal

regulations of the internal and external relations of the Church. In the case

of canon law, the variety of authors is greater, Abbas Panormitanus (1386-1445) (see annexed catalog) being the most important, a Benedictine, expert in canon law, and professor

of the Universities of Parma, Siena and Bologna. The work possessed by Brother

Cristóbal, Commentaria in decretales, was precisely

that which earned him great authority. Other important authors of canon law are

Carolus Ruinus Regiensis (1456-1530) (see annexed catalog) and Brother Domingo de Soto (1494-1560) (see annexed catalog), one of the great

Dominican authorities in theology and law, and one of the authors that Brother

Cristóbal cites in the Constituciones, as the author he had

studied in Spain: "... and so we study, hearing in voice the course of the

wise father Brother Domingo de Soto[42].” Domingo de Soto was a disciple of Francisco de

Vitoria and a defender of the position of Bartolome de

las Casas with respect to the condition of equality with which the Indians should

be treated. Brother Cristóbal, who studied the books of Soto[43], applied this position in Santafé in defending the

right of the Indians to communion, to eliminate "... the pernicious abuse

that is established in the Indies, principally in this kingdom, of denying

Communion to the Indians, almost universally, even at the hour of death.[44]" The denial of Communion to the Indians was part

of the thesis that defended the inferiority of the Indians with respect to the

Spaniards and which was the object of a complex debate in the sixteenth century

in Valladolid, a debate that Domingo de Soto participated in, defending the

position of the priest de las Casas. The position of Brother Cristóbal with

respect to the debate on the Indians is clear, as is his position within the

Dominican school that predominated in Salamanca, as evidenced by the texts

chosen to donate to the library of the Colegio Mayor del

Rosario. In academic terms, Brother Cristóbal was part of the new Dominican

scholasticism. On the other hand, Domingo de Soto was

one of the most read authors in America along with the theologian Bartolomé de Medina,

judging by the lists of books published by Irving Leonard[45].

Medical books (11 in total) constitute the third

group. The most important authors are Galeno (130-200) and his commentators,

like López Canario and Antonio Brasavolus see annexed catalog). Also, the

work of F. Gentilis on Avicenna is found. Brother Cristóbal put a lot of effort

into creating a Faculty of Medicine, given the need for doctors in New Granada,

as was already established in the previous chapter. This is how the Royal

decree of Felipe IV gave license to open a Faculty of Medicine:

I hereby grant and concede to the said Archbishop the license and authority

to found the college in the City of Santa Fe, with the same honors and privileges

as those enjoyed by the Archbishop of Salamanca, and to read to the collegians

[…] the doctrine of Saint Thomas, jurisprudence, and medicine, by people who

graduated from these faculties[...][46]

However, this faculty only came to work truly at the eighteenth century,

as was already noted.

The next subject in importance by the number of

volumes is the one of sacred scriptures, with a total of 10 books. It mainly deals

with commentaries on the books of the Old Testament, written by theologians.

The most important author is Caietanus Cardinalis (Thomas de Vio) (see annexed catalog) (1469-1534).

Cajetan, born in Gaeta, was one of the great representatives of scholasticism

in Italy and, in addition to the commentaries on the Holy Scriptures,

he was recognized above all for his comments on Saint Thomas and a conception

of the analogy that exerted a very strong influence among the Thomists[47]. His books had a wide circulation in America and

Europe and he was one of the authors most studied by the Dominicans. The books

donated by Brother Cristóbal are 4 volumes with commentaries on the Pentateuch,

the historical books, the Psalms and the book of Job. There are also commentaries

on several books of the Old Testament of the Jesuit Nicolas Serarius (see annexed catalog) (1555-1609), which Brother Cristóbal quotes in his

writings.

Likewise, there is a commentary by Alvarez de Medina (see annexed catalog) on the book of Isaiah, one by Octavius Tufo (see annexed catalog) on the Ecclesiastes and the volume by the

Jesuit Ioannes Antonius Velázquez (see annexed catalog) on the Psalms. These books of the Old Testament, often

quoted by Brother Cristobal in his writings, were widely used in the Spain of

the Golden Age, especially among the moralists who were followers of stoicism, who

took a particular form in the peninsula as described by Ángel del Río[48]: "Facing the 'support and renunciation' of

Epictetus, the Spanish moralist says 'endure and wait' ". He further adds:

"Seneca's severe morality is now reinforced by the resignation of the Book

of Job and by the echo of the ‘vanitas

vanitatum’[49]", as shown, for example, in La cuna y la sepultura by Francisco de Quevedo, precisely the

same book that he dedicated to Brother Cristóbal de Torres.

Criminal law is

represented by 9 books, in a great majority by the Roman jurist Prosperus

Farinacius (1554-1618). There are the

7 volumes of his complete work. There are, in addition, two volumes by Ioannes

Zilettus, both of them great jurists of the time.

Dogmatic theology, for its part, is represented by

several authors of great importance at that time in the peninsula. Most of

these books were published in Spain (Salamanca, Alcalá de Henares, Valladolid). Most notable is Francisco Suárez (1548-1617) (see annexed catalog), scholar, polymath,

professor, theologian, jurist and the highest representative of Jesuit Neo-Scholasticism,

a great commentator on Saint Thomas, and Bartolomé de Medina (see annexed catalog), who also

made a commentary on Saint Thomas.

There are 7 books of astronomy, packed into a single

volume whose central work is the The Sphere of the

World by Joannes de Sacrobusto or Sacrobosco (John of Holywood). This is a

treatise based on the astronomy of Ptolemy that constituted the fundamental

textbook of astronomy between the thirteenth and seventeenth centuries.

Sacrobusto (1195-1256) was an English Augustinian monk, and professor of

astronomy at the University of Paris. He wrote his The Sphere of the World in

1220 and thereafter it was the most studied book of astronomy in European

universities until the eighteenth century, when the Church finally accepted the

heliocentric theses of Copernicus and Galileo and astronomy changed radically.

It was the first book of astronomy that was printed in 1472 and by the year

1570 the book had more than 120 editions in several European cities[50], among which the one of Brother Cristóbal of 1508 is

counted. Translations also proliferated, like that of the cosmographer Jerónimo

de Chaves, into Castilian in 1545, where he not only translated the The Sphere

of the World but also added a series of tables, confirmations and commentaries[51]. This shows how important the book was in the

sixteenth century.

The miscellany of astronomy also contains a short

commentary by Bartholomeo Vespucius, Oratio de laudibus astrologiae, which was

found in the Index of prohibited books and is noted, like all other books in

this volume. The tradition of the Colegio Mayor de Nuestra

Señora del Rosario has long considered that the annotations in this miscellany are the work

of Brother Cristóbal. However, after a careful analysis of the writing, there

are great doubts about whether Cristóbal himself was the author of these

annotations, as was the traditional belief in the Colegio Mayor del Rosario.

There are 6 books on patrology, most of which consist

of the works of holy bishops and pontiffs containing sermons and homilies. Some

of them, such as those of Saint Leo the Great[52] and Saint Ambrose[53] are common on shipping lists and in American

libraries.

There are few books of history contained in the library.

The Historia General de España by the Jesuit Father Juan de Mariana

(1536-1624)[54]

stands out, one of the most read works in Spain at the time, as evidenced by its

many reprints[55],

and the Monarchia Ecclesistica by the Franciscan Father Juan de Pineda (1513

-1593)[56],

works that are also very common in American libraries.

Other topics such as procedural law, apologetics, philosophy,

probationary law, mysticism, politics, preaching and moral theology are

represented by very few volumes. Among these is the book by Juan de Solórzano

Pereira (1575-1655), De Indiarum Iure,

which was at the center of the discussion on the legitimacy of the Spanish

dominion of American lands that took place at the Universidad de Salamanca. The

copy of Brother Cristóbal, annotated and underlined, is from 1639.

The two books on philosophy also stand out. The first

is a curious example, not only because it is an incunabulum (1473), but also because

it appears as authored by Thomas Aquinas but apparently it is an apocryphal

book for which the term 'pseudo' has been added to the author's name[57]. It is not certain that the book has been read by

Brother Cristóbal as it is annotated and underlined with many different types

of letters and notations. The other copy of philosophy is a book by Erasmus of

Rotterdam, Opus de conscribendis

epistolis and Parabolarum sive

similium liber ab autore recognitus[58], also included in the Index of banned and expurgated

books of 1612[59], which prohibited or expurgated (as in the case of these

two books), an important part of the writings of Erasmus. The book is signed by

Brother Cristóbal but the annotations and underlining are, mostly, made by

another reader, whose signature also appears in the copy. Erasmus was one of

the most read authors in the peninsula in the sixteenth century, influencing in

an important way the Spanish humanism of authors like Juan Luis Vives and Juan

de Valdés, until he was prohibited and included in the Index. His books, as

noted by Irving Leonard[60], were widely read in America:

The repressive measures of the Counter-Reformation suppressed the name and

influence of the author of 'The Praise of Folly' from the Spanish-speaking

world less completely than is claimed. As this[61] and subsequent documents show, Erasmus's

writings that were not included in the ‘Index of prohibited books' were shipped

openly to the Spanish Indies, where they were read without special modesty.

Such is the case of the Opus de conscribendis epistolis, the work possessed by Brother

Cristobal, which can be found in several of the shipping lists transcribed by

Leonard, but which, however, was expurgated as was already noted.

4. By way of synthesis

In this article, we made a tour of the library of

Brother Cristobal de Torres, a prolific reader of the seventeenth century in

New Granada, Archbishop of Santafé de Bogotá and founder of the Colegio Mayor

de Nuestra Señora del Rosario. The pass through his

library shows us several peculiarities that require attention. On the one hand,

it was not his personal library, of which little is known, but rather a library

that Brother Cristóbal donated for the establishment of the Colegio Mayor; the constitutions of

this college, however, clearly differentiated it from the educational

institutions existing in Santa Fe de Bogotá in the mid-seventeenth century,

since they established an express restriction on ecclesiastical governing and

training, in the midst of a cultural context in which education was almost

strictly concentrated in religious communities and oriented almost completely

towards the task of evangelization. This explains why almost 70% of the books

that make up this library are about law, and for the most part about civil law;

strictly religious books constitute only 17% of the books acquired for

teaching. It must be considered here, however, that this was a historical

moment in which the fields of theology were being narrowly defined from other

knowledge, including law and medicine, but in this respect, it must be

considered that the particular decision of the Archbishop of Santa Fe was in

this case in favor of the secular disciplines, not because of the desire to

break with the New Granada tradition, but because of the desire to continue

with the tradition of Salamanca.

The decision of the Archbishop of Santa Fe in favor of

law and medicine is explicable from a historical and cultural point of view.

This religious man wanted to open spaces for Spaniards and secular creoles

within the labor market of New Granada, not only because of the crisis of the encomienda that affected the income of

the non-indigenous population, but also for the perception of the positive

results that this policy had had in Spain, where the scholars had found a

mechanism of social and professional mobility by means of their insertion in

educational institutions.

The library also allows us to reflect on the

circulation of knowledge in New Granada, and to discuss the thesis of isolation

that is usually proposed for its description during the seventeenth century.

Along with other libraries of the time located in Santa Fe de Bogotá, it is

observed that the group of literary authors, and of the diverse disciplines,

correspond to the set of authors "in fashion" in peninsular Spain at

the beginnings of the 17th century, referring to the authors who

specialized in law and jurisprudence, as well as in relation to the authors of

literary works of the golden century. It is not, however, proposed that

knowledge circulated widely in all spheres of the society of New Granada, since

there were indeed important restrictions on access to knowledge derived from

the limitations on entering educational centers (a condition of old Christians

and purity of blood) and language (a large amount of the works were written in

Latin), but the existence of several established communities of interpretation can

be presumed among the small group of creoles and Spaniards.

APPENDIX 1

Catalogue of the library of Brother Cristóbal de Torres[62]

APOLOGETICS

Hosius Cardenalis D. Stanislaus, Opera. Confessio cath. fidei. Propugnatio verae doctrinae adversus

Io. Brentium. De expreso Dei verbo. Dialogus de eo, num calices laicis, et

uxores sacerdotibus permitti, ac divina off. vulgari

lingua agere fas sit, Lugduni, imp. Iac Iuntae,

1564, vol. 1, pags. 750, 34x22.

SACRED TEXTS

Caietanus Cardinalis (Thomas de Vio), Commentarii

illustres in quinque Mosaicos libros, annotationibus a F. Antonio Fonseca

Lusitano, Parisiis, imp. Guill. de Bossozel, 1539,

vol. 1, pags. 512, 34x22. (Con anotaciones)

Caietanus Cardinalis (Thomas de Vio), In

authenticos Veteris Testamenti historiales libros Commentarii, Romae, imp.

Antonii Bladi Asulani, vols. 1, 1533, pags. 398, 32x22. (2 anotaciones)

Caietanus Cardinalis (Thomas de Vio), Liber

Psalmorum ad verbum ex hebraeo versorum, vol. 1, pags. 281, 32x22. (Con

anotaciones)

Caietanus Cardinalis (Thomas de Vio), In

librum Iob commentarii et respontio ad censuras (XIV) Parisiensium, Romae,

imp. Anto. Bladii, 1535, vol. 1, pags. 140, 29x21.

Pinto, Fray Héctor, In Ezechielem

prophetam commentaria, Salamanticae, imp. Ildefonsi

a Terranova, 1581, vol. 1, pags. 654, 29x21. Expensis Lucae a Iunta ed.

PATROLOGY

S. Gregorius, Papa, Opera Omnia, Parisiis, imp. Claudii Chevallonii, 1633, vol. 1, pags. 465, 40x26.

S. Leo Magnus Romanus Pontifex, Opera omnia quaereperiri potuerunt,

Parisiis, imp. Claudii Morel, 1614, vol. 1, pags. 539, 35x23, ed. Ioannis

Vlimmerii.

S. Maximus Taurinensis Episcopus,

Homiliae, Parisiis, imp. Claudii

Morel, vol. 1, pags. 546, 703, 35x23, ed. Ioannis Vlimmerii, an. 1614.

S. Petrus, Chrisologus

Archiepiscopus Ravennatis, Sermones,

Parisiis, imp. Claudii Morel, 1614, vol. 1, pags. 445, 35x23, ed. Ioannis

Vlimmerii.

DOGMATIC THEOLOGY

Choquetus, O. P. Hyacinthus, De origine gratiie sanctificanis, libri tres,

Duaci, imp. Balth. Belleri, vols. 2, 1633, pags. 878 y 878, 22x17.

(Duplicado. Son dos ejemplares del mismo libro?)

González de Albeida, Ioannes, Commentriorum et disputationum in primam

partem Angelici Doc. D. Thomae, primus tomus, Compluti, imp. Io. Gratiani,

1621, vol. 1, pags. 987, 30x21.

Medina, F. Bartholomeus, Expositio in

tertiam Partm Divi Thomae, Salamanticae, imp. Mathiae Gasti, 1584, vol. 1, pags. 1132, 29x21.

FALSE RELIGIONS. SUPERSTITIONS

Vespucius, Barholomeus, Oratio de laudibus astrologiae, Venetiis,

imp. Io. Rubei & Bernardini, 1508, vol. 1, pags. 4, 31x22. (Con anotaciones

y autógrafo de Fray Cristóbal).

POLITICS

Solórzano, Ioannes de, De Indiarum Iure, tomus alter, sive de justa

Indiarum Occidentalium gubernatione, Madrid, imp. Francis. Martínez, 1639,

vol. 1, pags. 1706, 30x21.

PENAL LAW

Farinacius, I. C. Prosperus, Opera omnia, Praxis criminalis, L. 2. Decis.

S. Rotae, etc., Duaci et Lugduni, imp. Wyon, Cardon, Keerbergii

(Antuerpiae), 1616/20, vols. 14, 34x25.

Zilettus, Ioannes Baptista,

U.I.D., Consiliorum sive responsorum ad

causas criminales ex jurisconsultis veteribus et novis, Venetiis, imp. Francisci Ziletti, 1582 y 1579, 30x21.

CIVIL LAW

Anguiano, Christophorus de, Tractatus de legibus et constitutionibus

Principum et aliorum judicum Ordinariorum, tomus I, Granatae, imp. P. de la

Cuesta, 1620, vol. 1, pags. 552, 29x20.

Azpilcueta Navarri, Martinus, Commentaria et tractatus hucusque editi et

in tres tomos distincti Tomus III, Venetiis, imp. Damiani Zenarii, 1588,

vol. 1, pags. 163, 34x22.

Baldus de Perusio, Opus aureum super feudis cum additionibus D.

Andreae Barbaciae necnon aliorum clarissimorum doctorum, Venetiis, imp.

Philippi Pincio, 1516, vol. 1, pags. 90, 43x28. Niviter impressum.

Baldus, Ubaldus Perusinus, Super toto codice, additionibus Io.

Francisci de Musaptis, et cum apostillis Alexandri de Imola, A. Barbatiae et

Celsi Burgundi, Lugduni, imp. Ioannis Moylin, 1526, vol. 3,

42x29. Cum repertorio ac lectura super toto codice.

Bartolus de Saxoferrato, In secundam infortiati partem Praelectiones,

Lugduni, imp. Iac. et Io. Senetoniorum, 1546, vol. 1,

pags. 190, 42x29.

Bartolus de Saxoferrato, Prima et secunda pars Commentariorum super

Infortiato, Lugduni, imp. Sebastiani Griphis, vol. 2, pags. 197 y 188,

42x29.

Bartolus de Saxoferrato, In primam et secundam Digesti veteris partem

Commentaria, adnotationibus, Alex. Barb. Seisell, Pom, Nicelli et

aliorum, Augustae Taurinorum, imp. N. Beuilaquae, 1577,

vol. 2, pags. 198 y 160, 43x29

Bartolus de Saxoferrato, In primam et secundam

Digesti novi partem Commentaria, cum adnotationibus, Alex. Barb. Seisell, Pom,

Nicelli et aliorum, Augustae Taurinorum, imp. N. Beuilaquae, 1577, vol. 2, pags. 180 y 254, 43x29

Bartolus de Saxoferrato, Secunda pars commentariorum super Digesto

Novo, Lugduni, imp. Sebastiani Griphis, 1527, 42x29 (con anotaciones)

Bartolus de Saxoferrato, Secunda pars commentariorum super Digesto

Veteri, Lugduni, imp. Sebastiani Griphis, 1527, vol. 1, pags. 158, 42x29

Bartolus de Saxoferrato, In primam et secundam Codicis partem

commentaria, Augustae Taurinorum, imp. N. Beuilaquae, 1577, vol. 1, pags.

187 y 125, 43x29

Bartolus de Saxoferrato, In tres Cidicis libros Commentaria, Augustae

Taurinorum, imp. N. Beuilaquae, 1577, vol. 1, pags. 58, 43x29

Bartolus de Saxoferrato, Prima et secunda pars Commentariorum super

Codice, Lugduni, imp. Sebastiani Griphis, 1527, vol. 2, pags. 195 y 128,

42x29. Additiones hujus operis: Alexandri Imolensis,

Andreae Barbatiae, Andreae de Pomate et Christophori de Nicellis.

Bartolus de Saxoferrato, In tres Cidicis libros praelectiones,

Lugduni, imp. Iac. et Io. Senetoniorum,

1546, vol. 1, pags. 69, 42x29

Bartolus de Saxoferrato, In primam et secundam partem Codicis

Praelectiones, Lugduni, imp. Iac. et Io.

Senetoniorum, 1546, vol. 2, pags. 195 y 126, 42x29

Bartolus de Saxoferrato, Consilia, Tractatus et Questiones,

Lugduni, imp. Sebastiani Griphis, 1527, vol. 1, pags. 153, 42x29

Bartolus de Saxoferrato, Repertorium singularium materiarum super

Lectura Bartoli, Lugduni, imp. Sebastiani Griphis, 1527, vol. 1, 42x29

Bartolus de Saxoferrato, In authentic. opus

Praelectiones, Lugduni, imp. Iac. et Io.

Senetoniorum, 1546, vol. 1, pags. 62, 42x29.

Bonavoglia, Ioannes Franciscus et

J. A. Riccius, Additiones novae et

Jasonis Mayni super secundam Codicis partem, Venetiis, imp. Iac. Iuntae,

1622, vol. 1, pags. 26 y 6, 41x28

Castro, Paulus de, In primam et secundam partem Digesti veteris,

Francisci Curtii aliorumque anotationibus,

Lugduni, 1544, vol. 2, pags. 172 y 129, 41x27.

Castro, Paulus de, Advenionicae in Digestum vetus et novum

praelectiones, Lugduni, 1544, vol. 1, pags. 94, 41x27.

Castro, Paulus de, In primam et secundam partem Digesti novi,

Francisci Curtii aliorumque anotationibus, Lugduni, 1544, vol. 1, pags. 83

y 98, 41x27.

Castro, Paulus de, Repertorium Sententiarum ac rerum quas in

Praclectionibus in Jus Universum Tradidit, Lugduni, 40x27.

Cornazzano, Barnabbas, Decisionum novissimarum Rotae Lucensis

centuriae duae, Francofurti, 1600, vol. 1, pags. 256 y 297, 34x21

Costa, Emmanuel, Omnia quae estant in jus canonicum et civile

Opera, Lugduni, imp. P. H. Phillip. Thinghi, 1584, vol. 1, pags. 646,

35x22.

Cuiacius, I. C. Iacobus, Tota Opera in corpus luris, Tomus II, III et

IV, Lugduni, imp. Io. Phillehotti, 1614, vol. 3, 34x22.

Durandus, Guilielmus, Tertia et quarta para Specu, cum

additionibus Ioannis Andreae et Baldi; Novissime auten cum additionibus Henrici

Ferrandat Nivernensis, Lugduni, imp. Iacobi Racon, 1520, vol. 1, pags.

184, 39x27. Ed. ultima, novissime in lucem edita.

Gravetta, Aymon, In primam et secundam ff. Novi, Augustae

Taurinorum, imp. Dominici Tarini, 1606, vol. 1, pags. 435, 36x24

Jason de Mayno Mediolanensis, In secundam Codicis partem commentaria,

Venetiis, imp. Iac. Iuntae, 1622, vol. 1, pags. 188, 41x28.

Jason de Mayno Mediolanensis, Prima et secunda super digesto veteri,

Lugduni, imp. Petri Fradin, 1553, vol. 2, pags. 196 y 202, 42x29. Cum additionibus

Francisci Ioannis Purpurati.

Jason de Mayno Mediolanensis, In primam Infortiati partem commentaria,

Venetiis, imp. Iac. Iuntae, 1622, vol. 1, pags. 190 y 15, 41x28.

Jason de Mayno Mediolanensis, Prima et secunda pars super Infortiato,

Lugduni, imp. Blasii Guido, 1553, vol. 2, pags. 208 y 187, 42x28. Cum

Additionibus Ioannis Francisci Purpurati.

López de Palacios Rubios,

Joannes, Gloscmata legum Tauri, quas

vulgo de Toro appellant, Salmanticae, imp. Io. de

Iunta, 1542, vol. 1, pags. 140, 30x21.

Maynard, J. C., D. Gerardus, Novae Tholosanae quaestiones juris scripti

per arresta Parlamenti Tholosani, quas e gallico in latinum transtulit

Hieronymus Bruckner, Francofurti, imp. Nicolai Hoffman, 1610, vol.1, pags.

580 y 96, 35x23. Ed. Petri Kopssii.

Menochius, J.C., Jacobus, Consiliorum sive responsorum libri,

Francofurti, imp. Wecheli & Gymnici, 1614, vol. 7, 37x24.

Naebius Lipsiensis, Sebastianus, Systema selectorum jus Justinianeum et

Feudale concernentium, Francofurti, imp. Jo. Saurii, 1608, vol. 5, 34x21.

Petra, Petrus Antonius de, Tractatus de fideicommissis, et maxime ex

prohibita alienatione resultantibus, Francofurti, imp. Mus. Palthenianarum,

1603, vol. 1, pags. 636, 34x21. Ed. prior.

Pinelus Lusitanus, Arius, Ad constitutiones C de bonis maternis,

Salmanticae, imp. Mathias Gastius, 1573, vol. 1, pags. 351 y 183, 27x20.

Purpuratus de Pinerolio J.C.,

Joannes Franciscus, In primam et secundam

Codicis partem commentaria, Augustae Taurin, imp. Jo. Beuilaquae, 1588,

vol. 1, pags. 108 y 116, 42x29.

Rebuffo de Montepessulano,

Petrus, Commentaria in Constitutiones

regias gallicas, Lugduni, imp. Sennetoniorium, 1555, vol. 1, pags. 475,

23x21.

Ripa, Joannes Franciscus A., In primam et secundam Infortiati partem

commentaria, Venetiis, 1602, vol 1, pags. 143 y 164, 41x28.

Rosate Bergonensis J.C.,

Albericus, Dictionarium juris tam civilis

quam canonici, Venetiis, 1601, vol. 1, pags. 368, 41x27.

Socinus Senensis, Bartholomeus, In Digesti veteris ac Infortiati rubricas,

leges adque omnes Gymnasiis usitatiores, Venetiis, imp. Juntae, 1605, vol.

1, pags. 286, 41x27, Ed. postrema.

Socinus Senensis, Bartholomeus, Consiliorum

Bononiensium ac Patavinorum volumen tertium, per D. Petrum Andream Gammarum

correctum, Lugduni, imp. Joan. Moulin (a. Lambrau), 1537,

vol. 1, pags. 123, 40x27.

Socinus Senensis, Bartholomeus, Ad Digestum novum et aliquot Codicis titulos,

Lugduni, imp. Glaudii Servanii, 1564, vol. 1, pags. 193, 41x27. Editi per

Vincentium Godemianum Pistorien. J.D.

Tessaurus Fossanensis, Antoninus,

Decisiones S. Senatus Pedemontani,

Augustae Taurin, imp. Io. D. Tarini, 1590, vol. 1, pags. 236, 35x24.

Tessaurus Gaspar, Antonius, Additiones ad novas decisiones S. Senatus

Pedemontani, Taurini, imp. FF. de Cavalleriis,

1604, vol. 1, pags. 280, 20x15.

Tiraquellus, Andreas, De jure constituti possessorii Tractatus,

Parisis, imp. Jacobi Keruer, 1550, vol. 1, pags. 180, 18x12.

Velázquez de Avendaño, Ludovicus,

Legum Taurinarum a Ferdinando et Joanna

Hispaniarum Regibus, utilissima glosa, Toleti, imp. Joa. et

Petri Rodríguez, 1588, vol. 1, pags. 204, 28x20.

Villalobos, Joannes Baptista A., Antinomia juris regni Hispaniarum, ac

civilis, in qua practica forentium causarum versatur, Salmanticae, imp.

Alexandri a Canova, 1569, vol. 1, pags. 190, 28x20

PROBATIVE LAW

Guterius, Ioannes, Tractatus de juramento confirmatorio et

aliis in jure variis resolutionibus, Madriti, imp. Ludov. Sánchez, 1597,

vol. 2, pags. 328 y 328, 30x21.

Guterius Placentinus, Ioannes, Tractatus de juramento confirmatorio et

aliis in jure variis resolutionibus, Salmanticae, imp. Jo. a Canova, 1574, vol. 1, pags. 250, 29x21.

Romanus, Antonius Gabriel, Conclusionum seu regularum ad materiam

probatoriam pertinentes libri septem, Romae, 1570, vol. 1, pags. 937 a 1660, 34x22.

PROCEDURAL LAW

Franchis de Perusio, Philipus de,

Lectura perutilis et valde quotidiana

super titulo de appellationibus et nullitatibus

sententiarum, Tridini, 1518, vol. 1, pags. 100,

42x29. Impensis Ioannis de Ferraris (a) de Ioalitis ac Girardi de Zeis.

CANON LAW

Ancharano, Petrus de, Super sexto decretalium, Lugduni, imp.

Io. de Cambray, 1531, vol. 1, pags. 217, 43x29.

Costa, Emmanuel, Omnia quae extant in jus canonicum et civile

Opera, Lugduni, imp. P. H. Phillip. Tinghi, 1584, vol. 1, pags. 646, 35x22.

Ruinus Regiensis, Carolus, Consiliorum seu responsorum, Lugduni,

imp. Hugonis et Haered, 1546, vol. 5, 42x28.

Sarmiento, Franciscus, Selectarum interpretationum libri tres et de

Reditibus Ecclesiae, Burgis, imp. Philip. Iuntae, 1573, vol. 1, pags. 130 y

71, 30x21.

Tuschi, Dominicus S. Onuphri

Cardinalis, Practicarum conclusionum

juris in omni foro frecuentiorum, Francofurti, imp. Erasmi Kempseri, 1621,

vols. 4, 36x24.

ASTRONOMY

Aliaco, Petrus de, Quaestiones subtilissimae in Spheram,

Venetiis, imp. Rubei et Bernardini, 1508, vol. 1, pags. 71 a

87, 31x22. (con anotaciones)

Capuanus, Franciscus, Theoricae novae planetarum Georgii Purbachii

astronomi celebratissimi, Venetiis, imp. Rubei et Bernardini, 1508, vol. 1,

pags. 64, 31x22 (con anotaciones)

Capuanus, Franciscus, Expositio Spherae, Venetiis, imp. Rubei et Bernardini,

1508, vol. 1, pags. 54, 31x22. (con

anotaciones)

Monterregio, Joannes de, Disputationes contra Cremonensia deliramenta

in planetarum theoricas, Venetiis, imp. Rubei et Bernardini, 1508, vol. 1,

pags. 90 a 94, 31x22. (con anotaciones)

Sacrobusto, Joannes de, Testux Spherae, cum brevi et utili

expositione eximii Artium et Medicinae doctoris Francisci Capuani Atronomiam in

Patavino Gymnasio legentis, Venetiis, imp. Rubei et Bernardini, 1508, vol.

1, pags. 2, 31x22. (con anotaciones)

Stapulensis, Jacobus, Commentarii in Spheram Joannis de Sacrobusto,

Venetiis, imp. Rubei et Bernardini, 1508, vol. 1, pags. 70, 31x22. (con anotaciones)

MEDICINE

Didacus, Merinus, De morbis internis, Burgos, imp. Ph.

Juntae, 1575, vol. 1, pags. 143, 29x20 (con anotaciones)

Forestus Almarianus, Petrus, Observationum et curationum medicinalium. De

pectoris pulmonisque vitiis et morbis, vol. 1, pags. 176, 32x20. Libri

16/28.

Gentilis, Fulginas, Super canones Avicenae, Venetiis, imp.

Scoti, 1520, vol. 4, 34x22. Aere et Sollerti cura Dom. Octaviani Scoti civis

Modoetiensis.

HISTORY

Chassenaeo, Bartholomeus A., Consuetudines

Ducatus Burgundiae, Fereque totius Galliae, Parisiis, imp. Io. Roiny, 1548, vol. 1, pags.

389, 33x21.

GENEALOGIES. DETAILS

Otálora Arce, Ioannes AB, Summa

nobilitatis Hispaicae et inmunitatis regiorum

tributorum, Madriti, imp. Ludovici Sánchez, 1613, vol. 2, pags. 363 y 363, 29x21.

APPENDIX 2

Number of books by theme

Number of Books Theme Civil

Law Canon

Law Medicine Sacred

Scriptures Penal

Law Dogmatic

Theology Astronomy Patrology History Procedural

Law Apologetics Philosophy Astronomy Probative

Law Genealogies Mysticism Politics Preaching. Moral Theology Moral

Theology General

Total

NN

Theme3

Bibliography

Arévalo, José María. “Rectificación y observaciones

a la biografía de Fray Cristóbal de Torres”, Boletín de Historia y Antigüedades, Bogotá: Academia

Colombiana de Historia, Vol. LII, No. 604-605, febrero y marzo 1965.

Ariza, Alberto, O.P. Fray Cristóbal

de Torres O.P., Arzobispo de Santafé de Bogotá, Bogotá: Ed. Kelly, 1974.

Carpintero, Francisco. “Mos italicus, mos gallicus

y el humanismo racionalista. Una contribución a la historia de la metodología

jurídica”, en Ius Comune, Frankfurt,

consultado en: http://www.franciscocarpintero.com/pdf/ArtiRev/%E2%80%9CMos%20italicus%E2%80%9D,%20%E2%80%9Cmos%20gallicus%E2%80%9D%20y%20el%20Humanismo%20racionalista,%20en%20%E2%80%9CJus%20Commune%E2%80%9D.pdf.

Chartier, Roger. El mundo como

representación. Estudios sobre historia cultural, Barcelona: Gedisa, 2005.

Coplestone, Frederick. Historia de la filosofía.

De Ockham a Suárez, Barcelona: Ariel, Vol. III, 1985.

Cristina, María Teresa. “La literatura en la conquista y la colonia” Nueva historia de Colombia, Bogotá:

Planeta, 1989.

Del Río, Ángel. “Estudio Preliminar” Moralistas castellanos, Buenos Aires: Clásicos Jackson,

vol. VIII, W.M. Jackson Eds, 1950.

Fortich Navarro, Mónica Patricia. Literatura,

historia y política: Una lectura de Don Quijote en la bibliografía colonial

neogranadina, Bogotá: Universidad San Buenaventura, 2008.

Giraldo Jaramillo, Gabriel. “El libro y la imprenta en la cultura colombiana”,

Santa, Eduardo, El libro en Colombia,

Bogotá: Colcultura, Imprenta Nacional, 1973.

García, María del Rosario.

Fray Cristóbal de Torres, un lector del siglo XVII, Tesis de doctorado,

Bogotá: Universidad Pedagógica Nacional, 2013.

Hernández de Alba, Guillermo.

Documentos para la historia de la educación en Colombia, Bogotá: Patronato

de Artes y Ciencias, 1969.

Hernández de Alba, Guillermo y Martínez Briceño, Rafael. Una biblioteca de Santa Fe de Bogotá en el

siglo XVII, Bogotá: Instituto Caro y Cuervo, 1960.

Jaramillo, Pilar. La producción

intelectual de los Rosaristas 1700-1799, Centro Bogotá: Editorial

Universidad del Rosario, 2004.

Leonard, Irving. Los libros del

conquistador, México: Fondo de Cultura Económica, 1996.

Muñoz Rojas, Catalina. “Una aproximación a la historia de la lectura en la

Nueva Granada: el caso de Juan Fernández de Sotomayor”, Historia Crítica, No. 22, Bogotá: Universidad de Los Andes, 2001.

Rivas Sacconi, J.M. El latín en

Colombia. Bosquejo histórico del humanismo colombiano, Bogotá: Instituto

Colombiano de Cultura, 1977.

Ruiz Martínez, Eduardo. La librería

de Nariño y los Derechos del Hombre, Bogotá: Planeta, 1988.

Santa, Eduardo (comp.). El libro en

Colombia, Colcultura, Bogotá: Imprenta Nacional, 1973.

Sidney Woolf, Cecil N. Bartolus of Sassoferrato, His Position in the History of Medieval

Political Thought, Cambridge University Press,1913.

Silva, Renán. Saber, cultura y

sociedad en el Nuevo Reino de Granada, siglos XVII y XVIII, Medellín: La

Carreta, 2004.

Silva, Renán. Los ilustrados de Nueva Granada 1760-1808. Genealogía de una comunidad

e interpretación, Medellín: Fondo Editorial Universidad EAFIT, 2002.

Soto Arango, D., Puig-Samper, M.A., Bender, M. y González-Ripoll, M.D.,

(Eds).Recepción y difusión de textos

Ilustrados, Madrid: Rudecolombia UPTC, Colciencias, Universidad de León,

Martin Luther Universitat, Ed. Doce Calles, 2003.

Torre Revello, José. El libro, la

imprenta y el periodismo en América, Buenos Aires: Publicaciones del

Instituto de Investigaciones Históricas, No. LXXIV, 1940.

Torres, Fray Cristóbal de, Constituciones

del Colegio Mayor de Nuestra Señora del Rosario, Madrid, imp. Juan Nogués,

1666, pags. 14, cuarto.

Uribe Ángel, Jorge Tomás. Historia de

la enseñanza en el Colegio Mayor del Rosario, 1653-1767, Bogotá: Centro

Editorial Universidad del Rosario, 2003.

To cite

this article:

María del Rosario García, “Libraries in 17th

century New Granada: The library of Brother Cristóbal de Torres at Colegio

Mayor de Nuestra Señora del Rosario”, Historia

y Memoria, No. 11 (July-December, 2015): 17-55.