Las voces de una

juventud silenciosa: memoria y política entre los otros jóvenes durante los

años 60 (Mar del Plata - Argentina)*

Bettina

Favero[1]

CONICET – UNMdP

Reception: 06/05/2015

Evaluation: 11/06/2015

Approval: 16/11/2015

Research and Innovation

Article

Resumen

Este trabajo busca observar las

imágenes y representaciones de la política que tenía la juventud argentina en

la década de los años sesenta del siglo XX, a través de entrevistas orales y

publicaciones de la época. El universo analizado contempla a aquellos jóvenes

que no militaron en partidos políticos ni participaron en grupos armados. Estos

“otros jóvenes” se insertaron en el mercado laboral al finalizar la escuela y

no realizaron estudios universitarios, recorriendo caminos culturales y

políticos distintos. De esta forma, se intentará analizar las actitudes

sociales y comportamientos políticos de estos, en función de una realidad

marcada por los procesos políticos e institucionales que se daban en la

Argentina de los años sesenta.

Palabras claves: Jóvenes,

Argentina, Años sesenta, Memoria, Política

“The voices of silent youth: memory and politics among young people

during the 60s” (Mar del Plata – Argentina)

Abstract

This paper

examines the images and representations of the politics of the Argentinian youth

during the sixties of the 20th century, through oral interviews and

publications from the period. The analyzed archive takes into account young

people who were neither involved in a political party, nor participated in

armed groups. After finishing school, this “other youth” entered the labor

market and did not receive a college degree, taking instead other cultural and

political paths. In this way, an analysis of the social attitudes and political

behavior of these subjects will be made, based on a reality marked by the

political and institutional processes that characterized the decade of the

sixties in Argentina.

Key words: Youth, Argentina, the sixties, memory, politics.

"Les voix d’une jeunesse silencieuse : mémoire et politique des

autres jeunes pendant les années 60 (Mar del Plata, Argentine)"

Résumé

Ce travail

cherche à identifier, par le moyen d’entretiens et des publications d’époque,

les images et les représentations de la politique construites par les jeunes

argentins dans les années soixante du XXe siècle. L’univers analysé réunit des

jeunes qui n’ont pas milité dans des partis politiques ni ont pris part aux

groupes armés. Ces “autres jeunes”, qui ont eu un parcours culturel et

politique différent, une fois terminés leurs études secondaires se sont

incorporés directement dans le marché du travail sans effectuer des études

universitaires. Notre but sera donc d’analyser les attitudes sociales et les comportements

politiques de ces jeunes, en fonction d’une réalité marquée par les processus

politiques et institutionnels propres à l’Argentine des années soixante.

Mots clés: Jeunes, Argentine, Années soixante, Mémoire, Politique

1. Introduction

The sixties of

the twentieth century in Argentina have been identified in historical studies as

a long decade, the manifestations of which were pronounced from the late 1950s

to the late 1970s and have been historiographically revised as years of

cultural expansion, the artistic avant-garde, and political rebellion[2]. Much of this

research was constructed by authors who reviewed that decade and took it as

their object of study, but who were also protagonists involved or spectators

with some degree of participation in it. In addition to providing details and

promoting a variety of possibilities for future research, it also marked the

period as a time plagued by impending changes and of generations in

"states of desire for community, not blood" in the words of

Passerini[3].

Adding a

broader view to this perspective, a set of historians analyzed the dualities,

ambivalences and cross-connections that occurred within this process of

cultural and political modernization, among different social groups defined by

youth, family and gender, and how that process of transformation impacted upon

the daily life of the sixties population[4].

The present work

intends to revise the sixties once again, considering the cracks that this

modernization and cultural rebellion produced within the society in question

and to observe in an alternative way, the avatars of a political culture marked

by proscriptions, violence and dictatorships[5].

Thus, it will seek to observe through oral interviews the images and representations of the politics that was part of the youth in the sixties. In this case, I will focus on a category other than that already worked by the historiography on young people, these are "other young people" who had to enter the labor market quickly, did not have university experience and travelled different cultural and political paths[6]. We will try to analyze, through oral interviews, the social attitudes and political behaviors[7] of these young people in relation to the reality that surrounded them, which was marked by the political and institutional processes that occurred in the Argentina of the sixties. To this wealth of voices, journalistic sources of the time will be added, such as the mass circulation magazines "Siete Días", "Panorama" and "Tía Vicenta"[8], which will allow us to recover other youthful experiences related to the topics to be discussed in the article. These publications, in addition to providing "readers' letters" that filter the opinions of many young people, also provide interesting reports and opinion polls on the relationship between politics and youth in those years.

For this study, interviews were used that were

conducted with men and women born between 1935 and 1945, who in the early 1960s

were between 15 and 25 years old, and who did not complete university studies

but in some cases completed high school and in others, only finished primary

education. Most of them began working as from a very early age for different

reasons, among which are highlighted the purely economic: to help at home or to

support the family because one of the parents was deceased. As for their reading

tastes, they all admit to having a modest library in their homes, among which

could be glimpsed the collections of "Robin Hood". It was also normal

to read comics and news magazines. Likewise, a passion for radio programs

marked these people in their childhood and adolescence, with programs such as

"Los Pérez García", "Que pareja", "Peter Fox" and

"Glostora Tango Club" being common denominators. The interviewees are

not all from the city of Mar del Plata, but have decided to live there in the

last years of their life at the time of retirement. Some of them were part of

Retirement Centers located in the city who voluntarily participated in the

interviews. As for the structure of these, they focused on questions about some

events in Argentine political life as well as on the role of political parties

and the armed forces in those years. It is important to clarify that most of

the interviews were carried out in 2002 within the framework of the project

"Politics and society in the Argentina of the twentieth century. The view

of the elderly[9]” and today form part of the "Word and Image Archive",

Center for Historical Studies (CEHis, by its acronym in Spanish) Faculty of

Humanities, Universidad

Nacional de Mar del Plata. The collection of interviews used was selected for a

double reason: firstly, for the information they provided on the theme to be

developed in this work and secondly, so as to compare the ages of the

interviewees and their youthful experience during the sixties.

The interviews are influenced by the context in

which they were developed. The witnesses have left their youth behind and are

in their old age, and therefore their reflections in relation to their younger

years are mediated by their experience of life. Nevertheless, they have

illuminated certain aspects that are sought to be analyzed. Thus, the oral

testimony "presents itself as a problematic historical document that tends

to place the structure of the individual mentality in the horizon of a lived social

history"[10], allowing the knowledge of the history of the

group based on the daily life of the subject and the whole of the reference

group.

2. Oral history and youth

Much can be said of oral history and its use in

different historical themes. From its beginnings in the 1960's to the present

day, the use of oral history has been significantly changed. In its origins, it

was fundamentally used to understand the communities and groups that "had

been silenced by the official history of great events"[11], this premise has been maintained over time. The

great protagonists of oral history are the so-called "voiceless",

those sectors of society that did not feature in the written history until that

moment. Thus, pioneering and key works have been seen that marked the course of

this methodology and which put actors silenced until that moment at the center:

workers, immigrants, farmers, just to name a few. At present, the protagonists

remain the same, what has changed is the theoretical and methodological

perspective of oral history.

From different sectors, some techniques and uses of

this way of writing history have been criticized in order to improve them. The

clear relationship between memory and oral testimony has also been deepened.

Specialists on the subject, such as Alessandro Portelli, mark these advances:

"oral sources are never definitive - not only because they will always be incomplete,

but because no person can manage to relate something in its totality nor avoid

changing after their story."

[12] The oral source is incomplete, like any other source.

What is interesting is its richness, its complexity and its subjective

dimension: "they are the stories of a human practice that is reconstructed

by the person who tells or narrates it through their own memories. From that

moment, the memory that selects and models the past according to the images

that the individual has of himself as part of a group plays a transcendental

role” [13].

In this case, the role of memory plays a prominent role.

The weight of the present on the memories of the past can influence responses,

especially in relation to questions that have to do with specific political

processes. Another point to keep in mind is that the witnesses are no longer

young, they are elderly, and therefore the lived experience changes,

undoubtedly, the story of that past.

Finally, a few words about youth. In their

relationship with oral history, some authors criticize the scant attention paid

to young people as social constructs and as emerging subjects[14]. Undoubtedly, working with oral sources favors the

study of this kind of actor. The key is to be able to frame the analysis at a

time when the protagonists are no longer young because when interviewing, we

find adults or elderly people in many cases older than 60 or 70 years. Perhaps

this is one of the greatest difficulties in writing an oral history about young

people who are no longer so.

Here the office of the historian should take

precedence, by which I mean to be able to study and analyze these testimonies

as social and historical constructions. A Spanish historian who

works on young people says:

[…] “youth as a

social phenomenon depends, rather than age, on the person's position in

different social structures, such as the family, school, work and age groups,

and the actions of state institutions which with their legislation alter the

position of young people in them. The existence of youth as a defined group is

not a universal phenomenon and, like all age groups, their development, form,

content, and duration are social and therefore historical constructs, because

they depend on the economic, social, cultural and political order of each

society; that is, its historical location and the way in which

"youth" is constructed in a society[15] […]

2. Young people as an

object of historical study; between permanence and change

From the old continent, it has been sought to analyze

and understand the role played by young people throughout history. Souto

Kustrín, analyzes this group as a theoretical object of the study of history

from different perspectives and concludes that where more progress has been

made "is in the study of the emergence and development of youth as a

social group". However, the author points out that a dialogue between the

social sciences and history would be lacking, in order to obtain a theoretical

framework that addresses the social aspects of the subject of youth[16].

However, as regards the definition of this object of

study, two European historians raised a series of questions that allow us to

think about and to try to define it:

[...] Is youth a period of life or a permanent

position, is it a positive moment or years of doubt, is it a moment of decision

and self-affirmation or a lapse of subjection to the will and approval of

elders? Are they people integrated into the society or alienated from it? […].[17]

The contradiction is the core of this definition, a

situation of ambivalence that characterizes this historical group and which has

led many historians to carry out studies on a period of the 20th

century, the 60s, in which young people appear as the indisputable protagonists

of that decade and acquire a historical range of analysis.

[18]

A good characterization of the youth of those years is

that expressed by Eric Hobsbawm:

[…] young people, now became an independent social

group. The most spectacular events, especially in the sixties and seventies,

were the mobilizations of generational sectors that, in less politicized

countries, enriched the record industry [...] The political radicalization of

the sixties [...] belonged to the young, who rejected the status of children or

even adolescents (that is, people not yet adult) while denying the fully human

character of any generation that was more than thirty years old, with the

exception of some guru or other […].[19]

What is interesting about this social group is the

ambiguous relationship that unites young people with the world of adults and which

is exemplified in the conflict between order and change. In this regard,

Sorcinelli and Varni argue that the young people "contemporaneously show the face of the rebel and that of the custodian in

regard to the ideas and customs that they are presented to with[20]."

Young people set in motion

forms of protest when living conditions and integration are threatened by rapid

social change, but they also know how to guard and protect the values of the

community, as well as the cultural and social order they consider to be threatened.

On the one hand, they aspire to defend a style of life and cultural formation

of their own, but on the other, they tend to renew their inherited mental

baggage.

They are therefore historical actors that could be

defined as ambiguous, with opposing positions, a sector that would be able

"to break with class or family solidarities to become bearers of a

collective renewal" or to "fall into the arms of the seduction of a

providential leader who has come to embody the new order of which they dream[21]."

It will also be the historical context that will allow

us to understand the behavior of these young people. Norbert Elias affirmed

that society was in a "transition period in which relationships of parents

and older children, strictly authoritarian, and other more recent, more

egalitarian ones are found simultaneously, and both forms are often mixed in

families"[22]. It was the period after the great wars, the times

when young generations were not willing to accept "conventional

civilizational regulations such as the commandments of the respective older

generations. [23]" That is to say that the years that followed the

second world war were decisive for a whole generation of young people, and in

some cases led them to political radicalization and in others they were realized

in the cultural and social changes that marked an entire age group.

Argentina was not alien to these changes since it

underwent a process of social and cultural modernization that called into question

the established values and practices, which generated a series of

transformations that marked a cultural gap between two generations. In this regard,

Juan Carlos Torre states that "it was in those years, and in tune with

international trends, that the outline of a new stratum was cut: the youth.

[24]" But not all young people went "on the path

of psychological and social emancipation in the same way, but all were exposed

to it": transformations in sexual morality, changes in sociability that

evaded the control of adults, the decline of the guardianship of parents and of

the family order[25], among others, were the elements that marked a before

and after.

In short, it is important to delve deeper into this

sector of society which is ambiguous, because it sought to impose the new but

also defended the traditional, it aimed to revolutionize some customs but also

maintained others. Young people who read Rodolfo Walsh but also Julio Cortázar,

Jorge Luis Borges or Leopoldo Marechal, who listened to Elvis Presley, Bill

Haley, Osvaldo Pugliese or Astor Piazzolla, who began to wear more jeans and

use less gel, who although they maintained the culture of the bolero, also

began to listen to rock. Who, in spite of the birth of television, maintained

the habit of listening to the radio and used to go to the cinema, although the

taste for Hollywood gave way to French and Italian cinema in those years:

"the imagination of many young people was being shaped by novels such as ‘On

Heroes and Tombs’ by Ernesto

Sábato, but also by the zambos of Cuchi

Leguizamón, the latest album by The

Beatles, the comic book 'El Eternauta' and, in daily doses, strips like 'Mafalda'

by Quino or the humorous cartoons of Landrú[26]."

3. Argentinian society in the 1960s

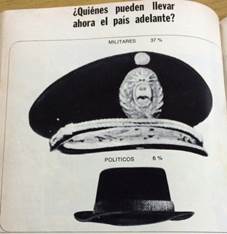

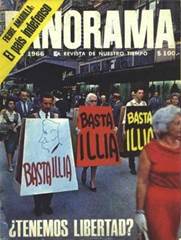

Image 1. Image 2.

Image 1: “Who

can lead the country now?”. Revista Panorama, nº 40 June 1966, 16.

Image 2: “Do

we have freedom?”. Revista Panorama, nº 36, May 1966.

In order to understand those "other young people"

it is fundamental to define the scene where the actors personified their

position in favor of order. I show this confrontation in terms of the idea that

arises when observing some vestiges of that time. On the one hand, a survey

conducted in 1966 that Guillermo O'Donnell[27] used for his research on this period. This indicated

that 66% of the respondents approved of the coup

d'état of that year, only 6% opposed it. On the other hand, two images from

the magazine Panorama from 1966 in which there is a photograph (Image 1)

attached to the following

question: Who can lead the country now? 37% think that it is the military and

only 6% endorse politicians. The other, a cover of the same magazine[28] (Image 2), shows some people walking along a street

in Buenos Aires with posters with the following phrase: "Enough of

Illia" and at the bottom of the cover the title: “Do we have freedom?

[29]”

The climate of the period reflected by these surveys

indicated a certain unrest among some sectors of society in 1966. Both

O'Donnell's academic work and the statistics that emerged from the magazine's

research provided an image representing the Argentine society of these years:

that of broad sectors of society in favor of military governments. This will

allow us to understand the context in which the political representations of

the "other young people" of our work can be analyzed.

To understand the opinion of that society it is

necessary to analyze what happened on the political plane[30]. The decade of the sixties was inaugurated with the

government of Arturo Frondizi, installed in 1958. A time in which the dichotomy

"Peronism-anti-Peronism" was attempted to be overcome and the

political system to be reordered. Frondizi had to rule between two power

factions: the Peronist unions and the military. In this way, he created

innovative policies that allowed his presidency to achieve aspects of success.

Nonetheless, the opposition of the People's UCR (UCRP, by its acronym in

Spanish), the close relationship with the unions and the power of the armed forces,

overshadowed the achievements of the process of economic modernization and

accelerated industrialization.

With the March 1962 elections in which nine Peronist

candidates achieved victory, the lack of support from the opposition parties

and the military forces to the Frondizi government was a fact. Thus, it was

agreed with Jose Maria Guido (president of the Senate) that he assume the

presidency until the call for new elections. During this interregnum, the

"Peronist problem" remained unresolved and the possible solutions to

it came from the hand of the army, in detriment to the electoral route.

The year 1963 being an electoral year, Arturo Illia

(UCRP) was elected President of the Nation with 25% of the votes. It was very

weak electoral support that was reflected in the percentage of blank votes

(21%) corresponding to the Peronism ban. Thus, Illia began his presidency,

which would last just under three years, truncated by a new military coup led

by General Onganía (1966). The government, despite the good economic results

achieved, received very little approval, from the public opinion that was polarized between the "social

revolution" that Perón challenged from exile and the "national

revolution" led by the armed forces. The latter would be imposed based on

the idea that they were the only ones that could impose order and accelerate

development.

The 1966 coup d'état, called the "Argentine

Revolution" led General Ongania to exercise a "technical" and

"apolitical" government. Its long-term objectives indicated that

under the new order, the country would go through an economic period, then a

social period and finally a political period. Differences with other power

factions (unions, political parties) as well as within the armed forces

themselves meant that the government could not achieve its goals, especially

those related to social and political aspects.

On the strictly historiographical level there has been

no study that has focused on the social history of this period, if there have

been attempts from the political[31]. Due to this, some studies will be referred to that

have the society in those years as a protagonist and that are relevant for this

analysis.

As an overture to the period and place considered, an

essay by Guillermo O'Donnell will be taken as a theoretical reference,

reflecting on this decade and the next and may be useful given its temporal

proximity to the period dealt with. In the first place, it is interesting to

observe the author's approach to the society of that time. He thought that

"it was authoritarian and violent and that it was also, fairly egalitarian[32]."

He also stated that the country

was far from being democratic and that Argentine society, marked by its

individualism and confrontation, lacking a "vigorous" liberal

tradition and with "a certain democraticness" tended to "arouse

authoritarianism, radicals and sympathizers[33]." In this respect, and regarding the succession

of military coups in the country, "authoritarian spirals" are referred

to.

[…] the attempted emergence of a power which,

with the point of bayonets, wants to constitute a main power, from there and

with the help of its eternal allies (those of class and the innumerable

authoritarian vocations that flourish in contexts like that) , to seriously

order a society up to that moment " out of place": those above, above

and commanding; those below, below and

obeying - and in any case, thankful for the paternal concerns that those above

will provide them with when things have been "straightened out": and

those in the middle, living their eternal schizophrenia: commanding and

obeying, but knowing clearly who to command and who to obey[…][34].

The idea of "ordering" society would seem to coincide

with all social groups. Each one from his place (up, down or in the middle) was

in accordance with the order that was imposed, in that way the different parts

of a machine were connected, which sought to discipline a chaotic society.

Although large sections of the population supported the military coups, they

were never able to sustain that imposed "order" and, as a consequence,

history, as represented by the authoritarian spiral, was repeated. O'Donnell

comments that:

[…] in Argentina, the repeated-and violent-triumphs of

those who have wished to impose this order have always been transient: they did

not feel triumphant, those above - doing what they learned first and then

taught the rest of society, they began to devour themselves, those below soon

explode and the middle again do not know who to command or obey. Up until now, as

neither the above nor (ay!) the transient losers had in the way the possibility

to discover the values and

mechanisms of democracy, then, in the next turn of the spiral, when each

ratified their motives and antagonistic visions, the game has been even more

confrontational, and even more brutal has been the attempt to impose an

"order" that was also increasingly authoritarian and brutal. All this

can change now, but to change it is necessary to realize the logic of these

spirals […][35].

Daniel James emphasizes that Argentina in those years

presented a game that was "impossible to resolve, where military coups and

illegitimate civil governments alternated," a fact that favored the loss

of legitimacy of political parties as well as the " decadence of the

notion of democracy[36]. " Thus, this lack of confidence in democracy

marked the political confrontations of the period and characterized a part of the

society. Many people who belonged to different social sectors did not identify

with democracy, had no confidence in it, and probably felt more secure with

military governments[37]. Within this large social sector were young people

born between 1935 and 1945 who had not entirely lived in a democratic

government (only Perón's first presidency reached its full term), had voted

sporadically, did not know about political practices or simply it seemed much

easier to them to delegate the power to govern to a sector outside the

democracy, the armed forces. As O'Donnell reminds us, "Argentina has been

programmed to generate epileptic and mass democracies, aborted by increasingly

brutal blows[38].”

In a study carried out at the time that we are dealing

with, used by Ricardo Sidicaro, Irving Horowitz proposed the concept of the

"norm of illegitimacy". With him, the author described the

"component of the Latin American political culture that accepted military

interventions in politics as normal, in order to treat the state as an agency

of power and to consider the rulers legitimate if effective at solving economic

and social problems, a view from which the lack of constitutional legality was

relativized, not only in terms of access to the control of state power, but

also of the most diverse violations of formal procedures of the representation

of society and the use of government instruments[39]." Transferring this to the Argentine case,

Sidicaro proposed that "this political culture became evident in the way

in which broad sectors of society accepted the coups d'état or palace coups, expecting the military to replace

civil authorities or military men without any basis other than the use of force[40]."

4. Representations of the politics of the 60s: the view of the “other

youth”

In this section I will try to analyze the social

attitudes and political behaviors of these young people in accordance with the

reality that surrounded them. By this I mean a category of study that has begun

to be used by historians and sociologists in recent years, and which seeks to

analyze the consensus or social and political indifference of the so-called

"ordinary people" in relation to dictatorial situations[41]. In this regard, there are examples used of papers that

beginning from the role of the press, business or workers, attempt to study

this phenomenon in both Spain and Argentina, but have not shone enough light on

the problem because of being biased in one sector[42]. Because of this, progress has been made in studies

on daily life that allowed a "refreshing and illuminating approach to

social experiences and attitudes under dictatorships[43]" and demonstrated their diversity and

difficulties so as to reduce them to categories such as opposition or

consensus. Thus, the use of oral and written sources allowed us to recognize

the variety and complexity of possible attitudes as well as to arrive at

conclusions that demonstrate the ambiguity of the phenomenon; in this case,

starting from the memory of the "ordinary" young of the sixties that were marked by coups

and military dictatorships.

One of the publications of the time stated that

"around the military, there is a diffuse taboo: 'they constitute a caste,

they get into politics, they do not fulfill their specific mission' or the

counterpart: 'they are the only ones who save us'. What is verifiable is an old

disconnect between the military and civilians[44]." Thus, the figure of the military man was

associated with order, discipline and progress. It was thought that military

governments could order the country as a whole, and bring things back to where

they should never have left. The military man was seen as a person with a lot

of power and strength, both elements needed to redirect things, although

sometimes they did not.

In the testimonies, can be seen a group of people who

believed in the order imposed by the military, who considered that the armed

forces could rule the country for a certain time and then call for elections.

They saw the suppression of democratic institutions as normal when they did not

work properly. Thus, the figures of Lonardi, Aramburu, Rojas and Onganía,

beyond their personal and ideological differences within the armed forces, were

assimilated into characters who were in the right place and time to "save

the country." Accordingly, "Panorama" magazine published after

the so-called "Argentina Revolution" in 1966: "on June 29,

Argentina awoke with a new government. The Argentine people seemed unsurprised.

Rumors that echoed in the national and international press had already warned

them of this inexorable fact. However, there was no certain clue as to the true

popular attitude towards the new authorities[45].”

A reflection of this are the answers of some of the

interviewees, to the question, ‘what kind of "government" did they

prefer in their youth, one elected by the vote of citizens or imposed by

military force?’, many of them marked their distrust towards democracy:

I

had no confidence in democracy or in political parties. Because democracy had

never worked. The political parties were like a football team, you became a fan

of one and you were with them, then you saw that the period when they ruled was

disastrous because there was always some calamity, everything started with

inflation, then ended up throwing them out[46].

It is interesting for understanding this group, the

idea of “throwing

them out”. At no time

did they consider the possibility of a democratic replacement for that

government that they considered chaotic, but rather the departure of the

government was the replacement by a military government that would, in theory,

solve the problems and give some tranquillity and order to that previous situation.

Is it possible to speak of a disenchantment with democracy in this age group?

They were born between 1935 and 1945, that is to say during military or

pseudo-democratic governments (Justo, Ortiz, Castillo, Ramírez, Farrell). Most

of their education developed during the Peronist government. Their first

democratic practice was in the 1958 or 1963 elections. In both cases, the

governments elected by vote (Frondizi and Illia respectively) were dismissed by

military coups. That is to say, they did not have a good experience with

democracy and lived through one of the most irregular political periods in

Argentine history, although not the only one. This does not justify their

passive attitude towards democracy, but it does help to understand and

contextualize their opinions on the matter.

But not only these voices refer to this idea, it is

interesting the suggestion made by the magazine "Siete Días" about

the process of political instability that had been taking place in Argentina

since 1930. To the question: "Who are those responsible for this

institutional fragility? The army or the political parties? ", The

response points to the situation of those years:

[…] practically no one stops

accepting as an irreversible fact of contemporary reality, the emergence of the

military in the different policies of the state ... Given the circumstances,

the armed forces acted as the only party with the weight of real power in

Argentina. The meetings of generals or the speeches of military chiefs' weigh

much more heavily on public opinion than party conventions. And something else:

political decisions are no longer discussed in committees (long before their final

closure), but in the War College and in the high military bodies […][47].

This paragraph reflects the opinion of a large sector

of Argentine society that did not have confidence in the political parties to

govern as the fundamental protagonists of a democratic government, but believed

that it was the armed forces that should be assigned that role. This

"irreversible fact" of the contemporary reality marks an entire era

and a whole society that accepted and supported this type of intervention.

In line with this distrust of political parties, a

survey by "Panorama" magazine in 1966 showed that 37% of the

population surveyed felt that it was the military who were better able to take

the country forward while 6% supported politicians. The rest of the percentages

were divided among businessmen, economists, workers, university students[48].

However, in view of this need for order emanating from the armed forces, what

was their role? Eduardo considers that when they came to power, people had:

“an expectation that it seemed that they solve

the problems and made the country work and when everything that followed was

the same, it was a disappointment. There was no other way to fix things, there

were no able people to do it. They had all the strength and the command to be

able to solve things but as they did not solve them then they were not able to

either. They

were not able because they did not want to[49].”

For his part, Mirta comments that "we lived

through the military governments like the telling of a story but not with a

happy ending because in some years, the early ones, we felt protected with

order and tranquillity but then later we felt that everything went sour[50]." In both testimonies, can be observed the

initial expectation and the subsequent disillusion, elements that have been

deepened with the passage of the years due to the temporal distance from the

facts and experiences lived.

Consistent with these testimonies, a note from the

magazine "Siete Días" reflected on the power of the military 38 years

after the first coup, from a joke that circulated in the Military College:

"for the cadets, the rank immediately above that of general is that of

President of the Republic -invented in the late 1930s." The journalist immediately

associated it with sarcasm: "What the military do is to eliminate the

group of politicians they do not like, to put other politicians in the

government, but of their preference." In fact, continues the note,

"this implies an inversion of the reality. Because it was almost always

the politicians who demanded the intervention of the military[51]." Here we can observe, on the one hand, the

naturalness with which the society accepted military coups, recognized in that

the rank above that of a general in the military mandate was that of president

of the nation. This acceptance was represented in a humorous volume in one of

the magazines of political humor most read in those years (Image 3)

[52].

Image 3: back cover of the magazine Tía Vicenta

(8/7/1963)

On the other hand, there is a widespread idea that it

was the politicians (opponents of the government of the day) who "beat the

doors of the barracks" to ask the military to disrupt the democratic government

and thus consolidate a new government. Consequently, and following this logic,

politicians did not go hand in hand with democracy, that is, they did not use

democratic channels to achieve power, but they sought to destabilize the

governments elected by the people and participate in the policies carried out

by military orders.

The first coup that the interviewees lived through in

their youth was the one made on March 29, 1962, when Arturo Frondizi was

dismissed as president of the Nation. The leader of the Union Cívica Radical Intransigente (UCRI) had come to power in the

1958 elections, through an electoral and political pact with Perón and in order

to obtain the support of the decisive Peronist vote for its candidacy, since

for that moment there was a proscription of the Justicialista party. Also, this coup d’etat truncated the first democratic president who had been voted

for by these young people.

"I

experienced this coup with great joy

but also with great sorrow. Changes like this cannot bear fruit, you

realize. Why? Because the military were always called for, by politicians of

one tendency or another. They were forced to carry out the coup. So that's not practical, they are not solutions "[53]

A change

was needed right? Maybe the military business would not be right, but it was

the only way it could happen, right? [54]

Their attitude towards the coup reflects the little democratic experience these young people

had, in addition to contemporaneousness with one of the most irregular

political periods in Argentine history, although not the only one. This does

not justify their apparent passive attitude towards democracy, but it helps to

understand and contextualize their opinions on this issue. In the following

testimony, different from the previous ones, one can observe the concern for

democratic institutions and the rejection of the coups.

That

event, which was later repeated, was an act of barbarism, carried out by the army,

by the armed forces, the constitution was a blank sheet, they acted as always.

It was prepared for a long time so as to achieve all the damage that they later

did to the nation. It was not an improvised act, it was a repeated act until

the republic was undone, by them and those who followed with that same plan, we

know them all[55].

Four years later, on June 28, 1966, a new coup led by General Onganía established

a government that eventually became an "authoritarian bureaucracy",

without a time limit, with long-term intentions and adding new prohibitions to

those already proscribed by Peronism[56]. The coup ousted

President Arturo Illia (Union Civica

Radica del Pueblo - UCRP), democratically elected in the elections of 1963

and in which he had obtained 25.14% of the votes[57].

Disastrous,

that was something completely unfair because Illia was a great person, maybe he

wasn’t what they wanted him to be or as clever, but he had many ideas and did

many good things, despite the short time he was in office. He was a great person. That

was very bad. [58]

It also seemed wrong to me, even though Onganía was

out of all the military men the one I held above all the rest, I saw a man who

seemed straight to me. Although Illia was a quiet man, but good, right? A

fighter, he struggled, a little bit slowly, but well[59].”

The military coup

of 1966 meant the gradual loss of democracy. However, in the descriptions of

President Illia, the interviewees echoed the characterizations of the time

("slow", "not very smart", "quiet") that they identified

him with a tortoise and that, for many historians, was part of the trigger and

subsequent support for the military coup[60].

I

think it was a mistake, Illia was a very honest president, no one could blame

him for putting his hand in the till, right? The proof is that the people of

Cordoba where he lived gave him a house because he had no home of his own. In

Cruz del Eje it was. What I can say about Illia was that he was a very, very

honest but slow ruler. He was slow but I think it was a mistake by Onganía. Although Onganía, despite being a military man,

made a good administrative government, for me. I will not talk about anything

else but the administrative government, I think it was good[61].

The candor, "do not put your hand in the till"

is also related to the deposed president and demonstrates the climate of the

period in which the interviews were carried out (in 2002 and 2004). This figure

is opposed by the de facto president

who, even if he had used the army to remove a constitutional president, remains

remembered for good governance at the administrative level. In the memory we

could say that "the whole past is simultaneous and is next to the present.

Different times are remembered at the same time, which is now. Therefore, a

story that starts from memory can be given a chronological sequence only by

large flows, by broad phases; but must always accept some degree of

indeterminacy, leaps back and forth[62]."

To delve deeper into the idea of political

attitudes, it was possible to observe in some interviews the opinion that the

interviewees had on two facts that would mark the end of the military

government of Onganía: the "Cordobazo",

of May 29, 1969, and the abduction and execution of General Aramburu[63], a year later in May 1970 carried out by the Montoneros organization. These events

convulsed Argentine society at that time, marking, on the one hand, the fact of

a student workers’ rebellion that was accompanied by large sectors of the society

of Cordoba and, on the other hand, the protagonism of armed violence that

reached characters related to high spheres of power.

Regarding

the Cordobazo, the memories are not

very clear. For some of those young people it was "an unprecedented event

of collective hope[64].” Lots of brains prepared to do things well, they

were as always, confused and that event that should have illuminated the

territory was only a light of hope. Others see it as a pivotal event at that

time, "it changed a period, did it not? Another started. I do not remember

well the consequences it had[65]." Nevertheless, one can also observe the

characterization of the revolt as violent and the moment when the violence

became visible to many of these young people: "I think it was excessive

because that could have ended in something very serious, could it not? Maybe

because the people of Cordoba at the time were going through much worse than

the rest of the country. Here in the province of Buenos Aires, many times the

economic ups and downs of other parts of the country were not felt[66].”

As for the kidnapping and execution of General

Aramburu, his relationship with the Montoneros

and with the guerrillas of those years, what

prevails, above all, was the rejection of violence, especially the "way"

in which he was assassinated[67]: "Well it was a crime against humanity, for me,

especially in the way they executed him." To this, the idea of these

youngsters of the armed organizations and their protagonism in those years, is

added: "It caused me a lot of indignation, it seemed to me like cowardice,

it did not seem right[68].”

Notwithstanding the violence of the event, the notion

of "revenge" was similarly related to the fundaments set out by the Montoneros at the time of his abduction

and execution[69]: "he seemed to me an okay person, despite the

fact that he had carried out the revolution of 55, but, I think things are fixed

in a different way and not like that, even less with the execution that they did,

so cowardly, they killed him[70]."

The testimonies mark two memories, on the one hand,

the violent execution that was part of the climate of the time, of the day to

day and that is not approved by any of them. On the other, the justification of

the same in accordance with the action of Aramburu a few years before. Agreeing

with the proposal of Sebastian Carassai, I believe that the memory of "social"

violence is determined by the degree of closeness to the events[71].

Finally, it is interesting to note how

the parallelism of the armed

organizations with the military forces, or the consensus of "the theory of

the two demons"[72], deepens in the opinion of the common people:

"the question of the Montoneros is

so debatable given that half of them belonged to the right and had been the peers

of Aramburu, they acted like the army without peace nor justice"[73]. Much has been discussed, intellectually, about this

but I think these young people conceived of this period as one of extreme

violence, of "one side and the other." Their political attitudes regarding

these facts are neither of approval nor opposition. Support for military coups

appears as something normal. It would seem that among this sector of the

population, the coup was the exit to

everything. The different situations experienced by the country had led to a

loss of civic-democratic meaning[74], that is to say, the only possible alternative to the

crisis of democratic governments was the disruption by force of the same. Confidence

had been lost in any democratic solution.

When listening to and rereading these testimonies, it

is not possible to stop comparing them with a work done by Alejandro Horowicz

focused on the last military dictatorship. In one of the chapters of his essay,

he made a puzzle with the letters of the readers of the newspaper La Prensa

between 1976 and 1983. According to the author, he "does not reduce the

whole of Argentine society into a text but I say, Argentine society was and

still is, covered by this text[75]." When reading these letters united by the hand

of Horowicz, the interviewees can be recognized in them: "when the armed forces

took power on March 24 and I listened to the text of the proclamation, I

exulted. The country had been saved. My euphoria is not superficial. There are

those who argue that it is, because, rather, one had to be sad because they

lost an opportunity to live democratically. Democracy is a word that expresses

a system of government and citizen participation in that government. But rather

than democracy or any other form of government, I believe in honesty. Without

honesty, there is no system of government that is good[76]." For this part of Argentine society, honesty

was placed above any form of government and, at that time, it was incarnated by

those who seized power by force.

5. Giving a voice to the silent youth: some final considerations

Through this polyphony of voices, I have tried to

observe the memories of a sector of the youth of the 60s. I am referring to

these young people who did not actively participate in the political militancy

of those years but who, nevertheless, voted, criticized or supported the

different governments of the day.

The support for the armed forces and the little

importance given to the democratic governments are a constant among them.

Obviously, having been born and passing their childhood and youth in a period

of innumerable coups d'état, makes

initial confidence in the military and distrust of politicians, commonplace.

Although in many of the testimonies the disillusionment with the changes proposed

by the armed forces is present in their memories; it is interesting to recover,

for this analysis, the initial illusion that occurred at the time of the coup. One of the ideas that emerges from

this work and that I will continue to investigate in the future is suggesting

that in these youth sectors there was a tendency towards the naturalization of

the coup. By this I mean the support

and the naturalness with which these young people took the access to power of

the military sectors through the coups

d'etat and their later disappointment with them.

The idea of social attitudes and political behaviors has been

attempted to be observed from two events that marked the Argentine history of

the late '60s and early 70s and which none of the interviewees could forget:

the Cordobazo and the kidnapping and execution

of Pedro Aramburu at the hands of the armed organization the "Montoneros". As I said earlier,

attitudes to these events mark a rejection of the violence exercised from

various sectors as well as an ambiguous position, the "do not get

involved" or "they must have done something" are perceptible in

the testimonies and in some way, the passage of time, validated this position

taken in youth. There is no reflection on what might have happened if they

"got involved" in what was happening, they simply keep the memory of

being as young as those who fought, but with whom they did not share the same

interests. What mobilized them and what could be recovered from the interviews,

although it has not been worked in depth in this text, was to achieve their own

objectives in life like getting a good job, having a good life, and having a

family. Politics was considered as something alien in which they had to

participate only at the time of elections, a relationship that we could

characterize as indifference and silence. Disbelief towards the function of

partisan politics and the valuation of an orderly society as a way of solving

its daily life was a characteristic of this youth sector which I intend to

continue to analyze in the near future from other historical sources[77].

Bibliography

Águila,

Gabriela y Luciano Alonso. Procesos represivos y actitudes sociales. Entre

la España franquista y las dictaduras del Cono Sur. Buenos Aires: Prometeo,

2013.

Altamirano,

Carlos. Bajo el signo de las masas (1943-1973). Buenos Aires: Ariel,

2012.

Andújar,

Andrea; Débora D’Antonio, Florencia Gil Lozano, Karen Grammatico y María Laura

Rosa. De minifaldas, militancia y revoluciones. Exploraciones sobre los 70

en la Argentina. Buenos Aires: Luxemburg, 2009.

Bartolucci,

Mónica. “Juventud rebelde y peronistas con camisa. El clima cultural de una

nueva generación durante el gobierno de Onganía”. Estudios Sociales (primer

semestre, 2006).

Botana,

Natalio; Rafael Braun y Carlos Floria. El régimen militar. 1966 – 1973.

Buenos Aires: La Bastilla, 1973.

Bra,

Gerardo. El gobierno de Onganía. Crónica. Buenos Aires: CEAL, 1985.

Carassai,

Sebastián. “Ni de izquierda ni peronistas, medioclasistas. Ideología y política

de la clase media argentina a comienzos de los años setenta”. Desarrollo

Económico 52, No. 205 (2012)

65-117.

Carassai,

Sebastián. Los años setenta de la gente común.La naturalización de la

violencia. Buenos Aires: S. XXI editores, 2013.

Cattaruzza,

Alejandro. “El mundo por hacer. Una propuesta para el análisis de la cultura

juvenil en la Argentina de los años setenta”. Entrepasados Revista de

Historia, No. 13 (1997).

Cavallaro,

Renato. Storie senza storia. Indagine sull’emigrazione calebrese in Gran

Bretagna. Roma: Centro Studi Emigrazione, 1981.

Cosse,

Isabella, Karina Felitti y Valeria Manzano. Los '60 de otra manera. Vida

cotidiana, género y sexualidades en la Argentina. Buenos Aires: Prometeo,

2010.

Cosse,

Isabella. Pareja, sexualidad y familia en los años sesenta. Buenos

Aires: Siglo XXI, 2010.

De Riz,

Liliana. La Política en Suspenso, 1966/1976. Buenos Aires: Paidós, 2000.

Del

Arco, Miguel Ángel, Carlos Fuertes, Claudio Hernández y Jorge Marco. No solo

miedo. Actitudes políticas y opinión popular bajo la dictadura franquista

(1936-1977). Granada: Comares editores, 2013.

Dogliani,

Patrizia. Storia dei giovani. Milano: Mondadori, 2003.

Elias,

Norbert. La civilización de los padres y otros ensayos. México: Ed.

Norma, 1998.

Favero,

Bettina y Mónica Bartolucci, “Entre caqueros y mersas. Las imágenes y representaciones

de los jóvenes en los ’60 a partir de la revista Tía Vicenta”. Ponencia

presentada en el Tercer Congreso Internacional Viñetas Serias. Narrativas

Dibujadas: debates, perspectivas y desafíos, Buenos Aires, 8 al 10 de octubre

de 2014.

Feixa I

Pampols, Carles. “Las culturas juveniles en las ciudades intermedias. Un

estudio de caso”. Estudios demográficos y urbanos 2, (1994) 339 - 356.

Fowler, David. Youth Culture in Modern Britain, c. 1920-1970. Londres: Palgrave Macmillan, 2008.

Galván,

Valeria y Florencia Osuna (comps.). Política y cultura durante el

“Onganiato”. Nuevas perspectivas para la investigación de la presidencia de

Juan Carlos Onganía (1966 – 1970). Rosario; Prohistoria, 2014.

Giachetti,

Diego. Anni sessanta, comincia la danza. Giovani, capelloni, studenti ed

estremisti negli anni della contestazione. Pisa: BFS, 2002.

Gil

Villa, Fernando y José Ignacio Antón Prieto. Historia oral y desviación.

Salamanca: Ediciones Universidad de Salamanca, 2000.

Hobsbawm,

Eric. Historia del siglo XX. Buenos Aires: Crítica, 2002.

Horowicz,

Alejandro. “Rapsodia consentida: las cartas del lector”. En Las dictaduras

argentinas. Historia de una frustración nacional. Buenos Aires: Edhasa,

2012.

Jelin,

Elizabeth. “Militantes y combatientes en la historia de las memorias:

silencios, denuncias y reivindicaciones”. Lucha Armada en la Argentina

(2010).

Lvovich,

Daniel. “Actitudes sociales y dictaduras: las historiografías española y

argentina en perspectiva comparada”. En Procesos represivos y actitudes

sociales. Entre la España franquista y las dictaduras del Cono sur. Buenos

Aires: Prometeo, 2013.

Levi,

Giovanni y Jean Claude Schmitt. Historia de los jóvenes. De la antigüedad a

la Edad Moderna. T. 1., Madrid: Taurus, 1996.

Manzano,

Valeria. “Juventud y modernización sociocultural en la Argentina de los

sesenta”. Desarrollo Económico 50, No. 199 (2010).

Mazzei,

Daniel. Los medios de comunicación y el golpismo el derrocamiento de Illia

(1966). Buenos Aires: Grupo Editor, 1997.

Muchnik,

Daniel. Aquel periodismo. Política, medios y periodistas en la Argentina

(1965 – 2012). Buenos Aires: Edhasa, 2012.

Novaro,

Marcos y Vicente Palermo. La dictadura militar (1976 – 1983). Del golpe de

Estado a la restauración democrática. Buenos Aires: Paidós, 2003.

Novaro,

Marcos. Historia de la Argentina. 1955 – 2010. Buenos Aires: Siglo XXI

editores, 2010.

O’Donnell,

Guillermo. El estado burocrático-autoritario. Triunfos, derrotas y crisis.

Buenos Aires: Editorial de Belgrano, 1982.

Passerini,

Luisa. Memoria y utopía. La primacía de la intersubjetividad. Valencia:

Universitat de Valencia, 2006.

Portelli,

Alessandro. Città di parole. Roma: Donzelli editore, 2007.

Potash,

Robert. El Ejército y la política en la Argentina 1962-1973. Segunda Parte.

Buenos Aires: Ed. Sudamericana, 1994.

Pucciarelli,

Alfredo. Empresarios, tecnócratas y militares. La trama corporativa de la

última dictadura. Buenos Aires: Siglo XXI, 2004.

Pujol,

Sergio, “Rebeldes y modernos. Una cultura de los jóvenes”. En: Violencia,

proscripción y autoritarismo (1955 – 1976), Nueva Historia Argentina.

Buenos Aires: Sudamericana, 2003.

Quiroga,

Hugo y César Tcach. A veinte años del golpe. Con memoria democrática.

Rosario: Homo Sapiens, 1996.

Sartori,

Davide. “La politica fuori dalla storia della politica”. Scienza e politica,

per una storia delle doctrine XXIV, nº 46 (2012).

Scarzanella,

Eugenia. Abril. Da Perón a Videla: un editore italiano a Buenos Aires. Roma:

Nova Delphi, 2013.

Sevillano

Calero, Francisco. Ecos de papel. La opinión de los españoles en la época de

Franco. Madrid: Biblioteca Nueva, 2000.

Sidicaro,

Ricardo. “Breves consideraciones sociológicas sobre la transición a la

democracia argentina (1983-2013)”. En Cuestiones de Sociología, No. 9,

2013 ().

Sigal,

Silvia. Intelectuales y poder en la década del sesenta. Buenos Aires:

Punto Sur, 1991.

Souto

Kustrin, Sandra. “Juventud, teoría e historia: la formación de un sujeto social

y de un objeto de análisis”. Historia Actual Online, N°.13 (2007).

Sorcinelli,

Paolo y Angelo Varni (a cura di). Il secolo dei giovani. Le nuove

generazioni e la storia del Novecento. Roma: Donzelli, 2004.

Sorensen, Diana. A Turbulent Decade Remembered:

Scenes from the Latin American Sixties. Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2007.

Taroncher,

Miguel Ángel. La caída de Illia. La trama oculta del poder mediático. Buenos

Aires: Vergara, 2009.

Taroncher,

Miguel Ángel. “Renovación, consumo cultural e influencia del “Nuevo Periodismo”

en la década del sesenta”, Ponencia del Decimotercer Congreso Nacional y

Regional de Historia Argentina, Buenos Aires, Academia Nacional de la Historia,

2005.

Teran,

Oscar. Nuestros dorados años sesenta. Buenos Aires: Punto Sur, 1991.

Torre,

Juan Carlos. “Transformaciones de la sociedad argentina”. En: Argentina 1910

– 2010. Balance del siglo, Buenos Aires: Taurus, 2010.

Tortti,

María Cristina. “Protesta social y nueva izquierda en la Argentina en la

Argentina del GAN”. En: La primacía de la política: Lanusse, Peron y la

Nueva Izquierda en los Tiempos del GAN, editado por Pucciarelli, Alfredo,

Buenos Aires: Eudeba, 1999.

Ysás,

Pere y Carmen Molinero. “La historia social en la época franquista. Una aproximación”. Historia Social No. 30

(1998).