What Makes a Teacher: identity and classroom talk*

Cómo se construye profesor: identidad y conversación en el salón de clase

Quest-ce qui fait un enseignant. Identité et conversation dans la salle de clase Résumé

0 que o faz professor: identidade e linguagem na sala de aula

* Scientific research article.

** Is a M time teacher at Universidad Pedagógica y Tecnológica de Colombia, Sogamoso, Colombia. He is the academic coordinator of the doctorate programme in Language and Culture. He holds a PhD in Education and Applied Linguistics from Newcastle University, U.K. He is a member of ENLETAM (Enriching Language Teaching Awareness) research group. He belongs to the Faculty of Sciences of Education, School of Modern Languages at the Universidad Pedagógica y Tecnológica de Colombia.

Recepción: 2 de abril de 2013 Aprobación: 30 de abril de 2013

Abstract

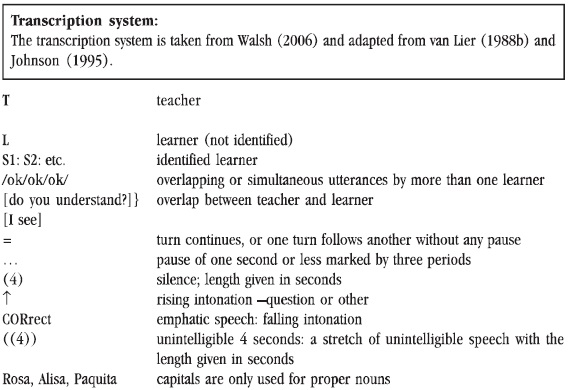

The purpose of this study was to gain a closer understanding of how teachers identities are co-constructed and shaped through their interactions. The Conversation Analysis (CA) approach was used to collect and analyze naturally-occurring spoken interaction. An experienced foreign language teacher was video-recorded while she was teaching English to a mixed-intermediate adult class in a monolingual Spanish setting. A two-hour lesson was transcribed in detail following the transcription system adapted from van Lier (1988b) and Johnson (1995). Three extracts of classroom conversation were analyzed at a micro-level of interpretation in an emic-empirical perspective in terms of the IRF/E cycle (Imtiation-Response-Feedback/Evaluation), turn-taking and repair. Results showed that the interactional flow of the lesson was constructed and maintained through asymmetric and empowered relations. The teacher seemed to determine, control and regulate most of the social actions that took place in the classroom, most of which were also entirely designed on a goal-oriented basis. The structure and imphcations of such an embedded institutional interaction might contribute to raising teacher awareness towards the effect of such a pedagogically restricted foreign language learning atmosphere.

Key words: Identity, classroom talk and interaction, conversation analysis.

Resumen

Este estudio tuvo como propósito lograr comprender de una forma más cercana cómo las identidades de los docentes se co-construyen y moldean a través de sus interacciones. La metodología del Análisis de la Conversación (AC) fue usada para recoger y analizar la interacción oral que ocurre de forma espontánea y natural. Una experimentada docente de lengua extranjera fue filmada mientras enseñaba Inglés intermedio a un grupo mixto de adultos en un contexto monolingüe Español. Una sesión de dos horas de clase fue totalmente transcrita siguiendo el sistema de transcripción adaptado de van Lier (1988b) y Johnson (1995). Se analizaron tres fragmentos de conversaciones en el salón de clase a un micro-nivel de interpretación desde una perspectiva émico- empírica en relación con el ciclo IRR/E (iniciación-Respuesta-Retroalimentación/Evaluación), manejo de turnos y reparación. Los resultados revelaron que el flujo de la conversación se construyó y mantuvo mediante relaciones empoderadas y asimétricas. El maestro aparece como la persona que determina, controla y regula la mayoría de las acciones que tomaron lugar en el salón de clase, las cuales al parecer fueron totalmente diseñadas sobre la base de los objetivos pedagógicos propuestos. La estructura e implicaciones de esta incrustada interacción institucional podría contóbuir para despertar la conciencia de los docentes sobre el efecto de tal atmósfera pedagógica restrictiva de aprendizaje de la lengua extranjera.

Palabras clave: Identidad, conversación en el salón de clase e interacción, Análisis de la Conversación.

Résumé

Cette étude a eu l'intention de réussir comprendre dune manière plus proche comment les identités des enseignantes se co-construisent et se modèlent travers leurs interactions. La méthodologie de l'Analyse de la conversation (AC) a été utilisée pour recueillir et analyser l'interaction orale qui se produit de manière spontanée et naturelle. Une enseignante expérimentée de langue étrangère a été filmée pendant quelle enseignait anglais (niveau intermédiaire) un groupe mixte d'adultes dans un contexte monolingue espagnol. On a transcrit une séance entière de deux heures de cours, en suivante le système de transcription adapté de Van Lier (1988b) et Johnson (1995). On a analysé trois fragments de conversation dans la salle de classe un microniveau d'interprétation dès une perspective émique-empirique en rapport avec le cycle IRR/E (initiation-Réponses-Retro alimentation/Évaluation), contrôle de tours et réparation. Les résultats on révélé que la fluidité de la conversation a été construite et soutenue partir des rapports de pouvoir et de symétrie. L'enseignant apparaît comme une personne qui détermine, contrôle et régule la plupart des actions qui ont eu lieu dans la salle de classe. Ces actions-là apparemment ont été complètement conçues sur la base des objectifs pédagogiques proposés. La structure et les implications de cette interaction institutionnelle intégrée pourraient contribuer éveiller la conscience des enseignants sur l'effet dune telle atmosphère pédagogique restrictive de l'apprentissage de la langue étrangère.

Mots clés: Identité, conversation dans la salle de classe et interaction, Analyse de la Conversation.

Resumo

0 estudo teve como propósito lograr entender de uma forma mais aprofundada como as identidades dos professores se co-constroem e adaptam através de suas interações. A metodologia de analise do diálogo foi usada para recolher e analisar a interação oral que acontece de forma espontânea e natural. Uma docente experiente em língua estrangeira foi filmada em quanto ensinava inglês em nível intermediário para uma turma mista de adultos num contexto monohngue espanhol. Uma única aula de duas horas foi gravada e transcrita segundo o sistema adaptado de Van Lier (1988b) e Johnson (1995). Analisaram-se três fragmentos do dialogo na sala de aula num nível de interpretação desde a perspectiva emico-empírica com relação ao ciclo IRR/E (Inicio- Resposta - Retroalimentação/avahação), administração de turnos e reparação. Os resultados revelaram que o fluxo de conversação se construiu e manteve por meio de relações imponderadas e simétricas. O professor se identifica como a pessoa que determina, controla e regula a maioria das ações que tomaram o lugar da sala de aula, as quais ao que parece, foram totalmente planejadas na base dos objetivos pedagógicos propostos. A estrutura e implicações da engajada interação institucional poderia contribuir para acordar a consciência dos docentes sobre o efeito da atmosfera pedagógica restritiva da aprendizagem da língua estrangeira.

Palabras chave: Identidade, conversação na sala de aula e interação, analise da conversação.

1. Introduction

The purpose of this study was to gain a closer understanding of teachers professional identities from the perspective of interaction in the language classroom. Some new signs of regenerated conceptualisation of identity from the interest in classroom talk have attracted plenty of research in the field (Buzzelli &Johnston, 2001; Cullen, 2002; Hall & Walsh, 2002; Richards, 2006; Seedhouse, 2002). The language classroom is essentially a context where interaction is conceived to be of paramount importance for second language learning. What teacher and students display in terms of role, power, language choice, and/or interactional organisation is claimed to help to portray an interpretation of what makes a language teacher. Teacher identity (TI) is argued to be embedded within a framework of institutional empowerment that directs most of its dynamics and dimensions. By analysing some selected passages of the discourse that was mediated in a language lesson this paper attempts to explore the role of classroom interaction in forming, shaping, adapting and sustaining identities.

This paper begins with a general overview of identity by locating in time some of the most relevant contributions towards its definition, foundation and/or theoretical construct. This part of the study attempts to illustrate the evolving body of former and current trends in the interpretation of its nature. From the cognitive self towards a recent new direction that considers the emotional landscape of teachers as part of the nature of teacher identity, this brief historical summary tracks a field of permanent theoretical and research contribution. The study then concisely illustrates its methodology and research setting, before approaching some images of teacher identity from the analysis of three extracts that looked at their interactional implications in terms of the IRF/E cycle, turn-taking and repair. Each extract is described in detail. Those portraits of identity in interaction are used to support the claim that teacher identities are essentially constituted in discourse. The paper draws some general findings that, rather than being conclusive, open a door for future explorations and re-conceptuahsation.

The analysis of some of the revealed images of TI through the exploration of the complex dimension of the interactional structure of classroom talk is part of the contribution of this study. Although the expedition towards uncovering the interwoven universe of categories is linked to it, TI is still under research. Classroom talk is believed to help to portray some of the characteristics of teachers professional practices. It might also contribute to raise teachers awareness towards the assessment of the pedagogical value of classroom interaction and its effects on second language teaching and learning, for example. The evaluation of a strictly controlled goal-oriented system of task implementation, the interactional patterns which are manifested through an essentialist TRF/E talk system, the asymmetric power relation in terms of the turn-taking organisation or the role of repair that is mainly based on the correction of errors, unfold a research territory that might attract some more generations of researchers and scholars not only in Colombia but in any language classroom world- wide.

2. Historical Trends of Identity: Overview

Identity has been theoretically reconstructed since its early origins. Although the concepts of self and identity are often used interchangeably in the literature of teacher education (Day, C, Kington, A., Stobart, G., & Samons, P. 2006, p. 602), both are identified as complex notions that involve different areas of philosophy, sociology or psychology, for example. Cooley (1902; cited in Day., et. al. 2006) introduced the concept of the looking glass self and sees the formation of the self as «part of a reflexive, learning process by which values, attitudes, behaviour, roles and identities area accumulated over time...» (p. 602). Mead (1934) conceptualised it as a continuous process that is linked to social interactions and in which language and social experiences play a significant role. Gooffman (1959) furthered the discussion by introducing the debate that each person has a different number of selves and that each one behaves according to a particular situation at any given time. Ball (1972) expanded on professional identity by differentiating between situated and substantial identity a decade later. Situated identity means, for Ball, (1972) a malleable presentation of self that changes according to specific situations (e.g. within schools) and by substantial identity he points at a more stable condition that includes the way a person thinks about her/himself. Sikes, P. J., & Measor, L. W. (1985) also contributed by arguing that identity is never attained nor conserved for all. Ball & Goodson (1985) and Goodson & Hargreaves (1996) approached teacher identity via the explanation that the events and experiences in teachers personal lives significantly influence the way they perform their professional roles. Kelchtermans (1993) suggested seven interconnected areas for the consideration of TI: self-image, self-esteem, job-motivation, task-perception, future perspective, stability and vulnerabiUty.

Several researchers (Mas, 1989,1996; Hargreaves, 1994; Sumsion, 2002; Day., et. al. 2006) argued that teachers identities are constructed not only from the technical dimensions of teaching that include classroom management, lesson planning, or assessment for example, but also from «the result of an interaction between the personal experiences of teachers and the social, cultural, and institutional environment in which they function on a daily basis...» (Sleegers & Kelchtermnas, 1999, p. 579) • James-Wilson (2001) noted the relationship between personal and professional identities by the explanation of how teachers «feel about themselves and how they feel about their students...» (p. 29). Cooper & Olson (1996) asserted that TI is continually being informed, formed, and reformed as individuals develop over time and through interaction with others (p. 80). Another recent theoretical trend incorporates the emotional self as a central domain in the scrutiny of the nature of TI. An increasing number of studies comprise emotions as essential in the de-construction of the notion of identity (Day, 2004; Hargreaves, 1998,2001; Mas, 1996; Sutton, 2000; van Veen & Sleegers, 2005; Zembylas, 2003). The core argument in this is that teaching is full of emotions and that it is impossible to see teachers from solely technical domains.

This general overview of TI displays a multi-varied perspective of what makes a teacher. To see the teacher from his/her role within the classroom -a framework of pedagogically embedded interaction- or the institution where she/he works (professional identity) restricts its dimensions significantly. The complexity of feelings, emotions, conceptions or beliefs, for example, challenges the cognitive and social frontiers which have characterised some of the former and current trends on identity. In short, TI becomes a field of research and theoretical concern that engages scholars imaginations towards uncovering its own reality from fields such as knowledge, cognition, skills, emotions, roles, public-private Uves, feelings, beliefs or policies, among many others. They are in themselves fertile territories that have captured a renewed interest in the Uterature of education and applied linguistics in the last decade.

Talk and identity

Benwell and Stokoe (2006) trace some of the approaches that have focused on the analysis of discourse and identity. From a social constructionist perspective, identity «is a public phenomenon, aperformance or construction that is mterpreted by omer people. This coristruction takes place in discourse and other social and embodied conduct...» (p. 4). This represents in itself a great shift from previous views of identity as an internal cognitive account to a more postmodern approach that looks at it in terms of discursive and semiotic matters, in spite of the debate that emerges when some scholars see identity as reflected in discourse while others claim that it is dynamically constituted in it Discourse is used by people to accomplish social actions, which reveal who we are, how we talk, what we say or what we mean. That social construction of identity is accomplished, disputed, ascribed, resisted, managed and negotiated in discourse (Ibid, p. 4). Some other approaches such as critical social psychology, positioning theory or psychoanalysis also analyse the discursive construction of identity. It is difficult to explain each one of them in this paper due to word limitations.

There is also a constructivist research orientation that places the nature of identity within the framework of discourse and semiotic systems. The conversation analytic view, that informs the current study, looks at the way identity is performed and negotiated in discourse. This perspective concentrates on how interacts ascribe themselves in terms of the interactional patterns, the actions accomplished and the turn-taking organisational choices. Both constructionism and CA claim that identity is far more than a property or role but a characteristic that emerges in social interaction. CA is a method that informs the researcher about the sequential organisation of talk which is made crucial as interaction progresses.

Identity has been a field of research that has progressively attracted conversation analysts. Most of those studies have focussed on institutional rather than ordinary settings. The distinction between ordinary and institutional talk is a topic of obliged differentiation. While the first is defined as a form of interaction that is not enclosed to any specified context or to the accomplishment of pre-established tasks, the second is institutionally embedded and restricted to the achievement of predefined goals. Institutions are generally related to buildings such as schools, courts or hospitals, for example. The analysis of those complex connections between talk and the accomplishment of institutional goals might display an image of the way identity is co-constructed or negotiated in interaction.

The language classroom is geographically and interactively characterised with the label of institutional talk where asymetrical speaking rights, macrostructures and goal orientation and identity alignments with institutions, are some of the repeated features in its speech exchange system (Benwell and Stokoe, 2006). The teacher is generally in charge of asking questions, pre-allocating turns or maintaining or hmiting the flow of the conversation within pedagogical agendas; the sequential free-driven exchange system on ordinary conversations is far more regularly controlled and structured in the classroom setting. Teachers and students behaviour is oriented towards the attainment of pedagogical goals which are set in terms of interactional tasks. The category teacher / student is imphcitly dominant in the social relationship, although they are occasionally uttered in classroom talk. Lexical choices and linguistic functions are at the heart of classroom talk. This context of discursive practice challenges the re-conceptualisation of TI as a field of research and refreshes domains for new and updated understandings.

3. Methodology

Conversation Analysis (CA) is a methodology that focuses its interest on the interpretation of nalurally-occurring interaction. This section introduces a very brief account of the use of this approach that was started by sociologists Sacks and Schegloff as a sociological naturalistic observational discipline that could lead with the details of social action rigorously, empirically and formally...» (Schegloff & Sacks, 1973, p. 289) • This study does not expand on some of the ethnomethodological principles that sustain the research apphcation of CA, due to word limitation. However, CA is not related to conversation alone. It is mainly concerned with describing all modes of functions of talk in interaction and other forms of conduct such as body language, gesture, facial expressions, and so on (Schegloff, E. A., Koshik, I., Jacoby, S., & Olsher, D. 2002). Understanding the sequential organisation of talk and its interactional effects on interaclants are referred to as some of the contributions of CA.

The data transcribed from classroom talk in a Spanish monolingual context was used as a foundation for understanding teacher professional identity. An experienced foreign language teacher was video-recorded while she was teaching English to a mixed-intermediate adult class. A two-hour lesson was fully transcribed in detail following the transcription system adapted from van Lier (1988b) and Johnson (1995). The video-recording of the lesson forms part of a stock of training materials which are available for CA purposes at Newcasde University, UK. The lesson was transcribed in 2008 and some of the early findings were the results of explorations in the CA methodology. Further involvement in the study and practice of CA by the researcher as a PhD candidate and as a member and participant in some CA study groups, workshops and/or training sessions that took place at the same university regularly during the period of 2010-2012, consolidated the current achievements.

The emic standpoint studies behaviour from inside the system (Pike, 1967). There is no previous or predefined research questions or interest, the analysis emerges from internal. The analysis is entirely data-driven and emerges from any interactional feature that attracts the attention of the analysts. Three extracts of classroom talk were analysed at a micro-level of interpretation in an emic-empirical perspective in terms of the IRF/E cycle (Initiation-Response-Feedback/Evaluation), turn-taking and repair. There are no pre-established criteria regarding the extracts number or length for example, they are exclusively decided by the analysts.

Discourse setting

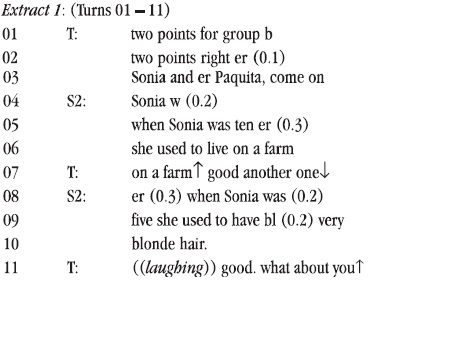

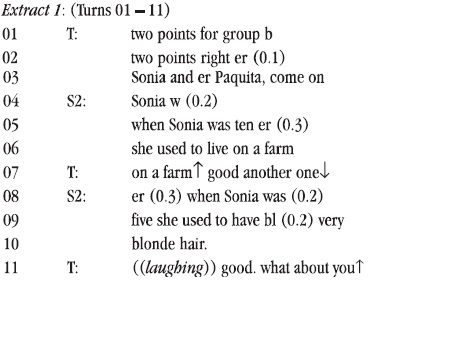

The discourse setting displays an image of a group of 20 adult-learners, 19 females and 1 male. They are studying English in a monolingual Spanish context. The students seem to be attending English lessons on a regular basis but for personal rather than academic purposes. This observation is mainly based on their age that ranges between 20 and over 50. The teacher appears as an experienced and well-grounded professional who displays a reliable and confident methodology for second language teaching. The lesson is taught through a friendly environment where there are laughs (turns 11 and 61) each others cooperation and understanding: lon a farm\goodanother one-l (turn 07) or in turns 22 and 24; or communicative encouragement: Sonia and erPaquita (.) come on (turn 03).

The teachers relaxed and non-threatening tone of voice, classroom management and displacement for example, portray a highly motivating atmosphere that promotes and creates opportunities for language learning. The learners on the other hand, display a high degree of learning engagement. They also show a good sense of resolution and willingness to taking part in the activities planned for the lesson, in spite of certain communicative limitations: the last sentence in (0.3) true and er (0.3) first is false» (turns 36 - 38). I might presume that they share a similar learning background without significant differences in communicative proficiency.

4. Data Analysis and Discussion

The interactional flow of the lesson is analysed from the perspective of the IRF/E cycle, turn-taking organisation and repair. The structure and implications of such an embedded institutional procedure are analysed at a micro-level of interpretation.

4.1. The IRF/E cycle

The Initiation-Response-Feedback/Evaluation -widely recognised as the IRF/E cycle-has attracted plenty of research since Bellack, A. A., Kliebard, H. M., Hyman, R. T. (1966) initial identification of a classroom structure based on three distinctive exchange patterns: solicit, respond and react. It was early recognised as an important teaching cycle, particularly recurrent and almost normative in the language classroom. Some years later Sinclair and Coulthard (1975) distinctively portrayed it as an outstanding interactional approach or «a more sophisticated discourse model of classroom interaction...» (Walsh, 2006, p. 41). The IRF/E cycle has been a matter of analysis, acceptance or criticism by Kasper (2001), for example, who claimed that learners could benefit more if teachers provide some opportunities for them to talk and interact. Being in one position or the other, it is still undoubtedly an «essential teaching exchange...» (Edwards, &Westgate, 1964, p. 124) that leads the social action of lesson participants, van Lier (1996) showed research results of classroom talk -between 50 and 70 per cent - that fell into the characteristics of this teacher-centred approach.

Extract 1 is used as an instrument to uncover what the teacher does and how this model of teaching and learning determines most of the classroom actions.

Extract 1 begins with a sample of the IRF/E interactional pattern. The teacher judges someone&s utterance in a previous turn as correct and immediately compensates group b with twopoints (turn 01) which is re-confirmed straight away without hesitation followed by the word right as a backchannel that categorically ratifies the decision made. A discourse marker 'er' and a 0.1 second pause are also used to hold the floor and to anticipate that there is no chance to question the teachers judgement (turn 02) and initiating another interactional sequence by verbally nominating either Sonia or Paquita as the next speaker. The teacher uses a word channel, come on (turn 03), as an invitation to carry on with the talk exchange. It is also a strategy to create a friendly atmosphere and to get a straightforward S2 response. This is perfectly understood by Paquita who decides to respond collaboratively to her circumstantial party (turn 04).

The interactional rules seem to be perfectly accepted by the task participants. A response is uttered immediately without any interactional gap or pause (turn 04). Because the teacher nominates the next partner unexpectedly, S2s reaction is also unexpected and makes her start her utterance wrongly: Sonia was (0.2) but after a short pause of 0.2 seconds she identifies the source of trouble and repairs it herself through a better structured answer that includes a hesitation marker er followed by a pause that allows her to re-compose the next part of the sequence and successfully produce a conditionally relevant paired utterance (turn 06). The teacher first re-confirms with a short question to the answer given, on a farm ↑(turn 07) that could be interpreted as echoing S2s response and immediately giving feedback or evaluating it as good and initiating the cycle repeatedly the same with the teachers initiation (turn 07); Student response (turns 08 - 10); and closing the sequence with the teachers feedback/evaluation in turn 11. The IRF/E cycle starts unalterable and predictably unmodified in turn 11.

What image of identity could an analyst gain from this interactional classroom chunk? Although there are different possibilities for tracking, some interpretation could be built from extracts 1 image of asymmetric power relations. The teacher is imphcitly recognised as the one who exercises the right to ask questions: on a farm↑ Good another onei (turn 07) and what about you (turn 11). Although Sonia and Paquita (.) come on (turn 03) is not precisely a question, this is an invitation to respond to the teachers enquiry, which could also be functioning as a question. S2 on the other hand, imphcitly accepts her role as a source of information and reacts consequently to this interactional achievement: when Sonia was ten er (0.3) she used to live on a farm (turns 05 and 06) or when Sonia was (0.2) five she used to have bl (0.2) very blonde hair (turns 08,09 and 10). The teacher monitors and re-confirms the answer or elicits new information (turn 07). S2 then responds, proceeds or carries on further social action (turns 05, 06 and 08 -10). The interactional organisation is then highly controlled and restricted by the teacher whose role is empowered from the dominant perspective (See turns 03,07 and 11). This type of interactional structure is a particular characteristic of institutional talk (Heritage, 2005).

4.2. Turn-taking organisation

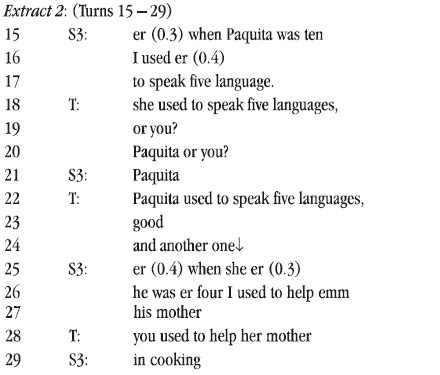

The accounts of turn-taking organisation appeared in the early stages of CA in the discoveries by Sacks, et. al. (1974). It basically means transitions that discourse participants follow in orderly fashion in a generally structured turn-by-turn basis. There are normative rules of interaction that each party follows by reference to one-party at a time, even though they are realized through designedly simultaneous talk... (Schegloff, 2000a, p. 48). The language classroom is essentially determined by the organisation of turn-taking. One speaking at a time emerges institutionally embedded and their effects on interaction are predictably influential. The first speaker, who is usually the teacher, initiates the talk specifically allocating the turn to one student who is usually selected as his/her counterpart. Extract 2 is used to illustrate some of the characteristics that were identified in the current analysis.

Extract 2 begins with S3 responding to a question asked previously by the teacher (turns 15 & 17). The turn has been allocated in advance and S3 is then selected as the next speaker. Although the turn starts with a hesitant discourse marker 'er' and a 0.3 second pause (turn 15), which probably means that as her contribution is pedagogically embedded to used to, it takes a while before S3 is able to re-organise it. Such a restriction forces her to misuse the personal pronoun T instead of she (turn 16) which is then followed by a hesitant discourse marker 'er' once again and a 0.4 second pause (turn 17). S3 then drops her intonation down and by doing so she is projecting the end of her turn. It is then read by the teacher who nominates herself straight away as the next speaker and gains control of the conversation by shaping S3s contribution in a more accurate way (turn 18) and asking for a confirmation check (turn 19) which is then re-confirmed through another question (turn 20). It is directly formulated to S3, which means that the teacher has pre-allocated the turn and already chosen the next speaker. She provides the right answer to the question asked and projects it as an intonational clue for the next speaker (turn 21). The teacher gains the interactional flow again and keeps the conversation going. She echoes the student contribution (turn 22) and evaluates it as good (turn 23) more in terms of pedagogical rather than communicative achievement. Turn 24 emerges in the form of a question that is addressed to the same S3. She begins with a hesitance marker 'er' followed by a pause of 0.4 seconds which allows her to accommodate her answer grammatically to what her counterpart is antidpating. S3 then attempts to react coherently (turn 2 5) but as her utterance is linguistically restricted, a hesitation in the form of a discourse marker 'er' and a 0.3 second pause show how problematic accomplishing the rules of the enquiry is. However, it is finally achieved in turns 26 and 27, in spite of more hesitations - er and emm- or grammatical inconsistency, - misuse of the personal pronouns he and I and the possessive his (turns 26 and 27)-. The teacher reads the source of trouble and intends to ask for clarification in the form of an interruption in turn 28, because there is a turn completion by S3 in turn 29.

The turn-taking system displays an interesting image of what makes a teacher: turn pre-allocation. The teacher gains the right to decide which person will speak (turns 20, 24 and 28) and the content of the contribution (turns 16, 17 or 21) which is tightly restricted by a learning goal manipulation -used to. The students are there to respond to the teachers exchange demands (see turns 21 and 25 - 27). There are no overlaps or significant gaps in the flow of the talk, and the teacher does not normally wait long for students to answer (Walsh, 2002). Questions are asked unidirectional by the teacher (turns 19 and 20) and SS do not normally exercise the right to initiate an exchange or pre-allocate a turn. Nevertheless, classroom participants seem to comprehend the rules of the interaction and both accomplish their communicative exchange system on a one speaker at a time basis and associated with referential frameworks and procedures that are particular to specific institutional contexts (Heritage, 2005: 106).

4.3. Repair

Repair is basically understood as the way interactants deal with communication problems. Seedhouse (2004) defines it as the treatment of trouble occurring in interactive language use (p. 143). A good number of the actions regulating the conversational patterns between teacher and learners has to be explained from the way repair circulates in the language classroom. The way teachers treat and manage the emerging talk gaps could be explained through a varied system of organization and structure.

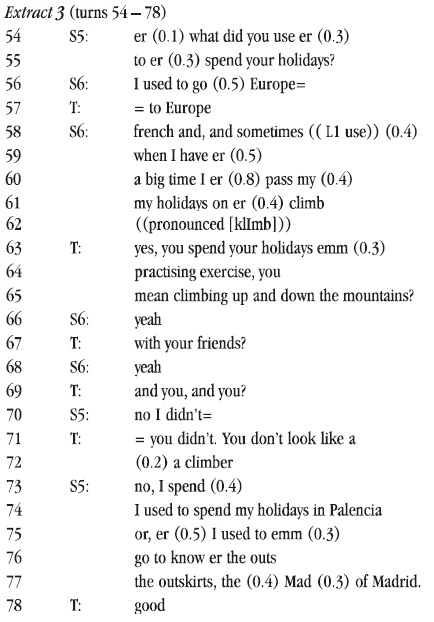

Seedhouse (2004, p. 145) identifies four different trajectories in which repair is accomplished». The speaker accounts for his own mistake and corrects it himself (self-initiated self-repaired); the speaker identifies the source of linguistic trouble, initiates repair and his counterpart completes it (self-initiated other repair); his counterpart notices the mistake, initiates repair and the speaker corrects it (other-initiated self-repair); and a situation where an interactant identifies the others mistake and corrects it (other-initiated other repair). Although repair could adopt the form of error correction - linguistic items measured as problematic in terms of syntax, pronunciation, appropriateness, morphology, among others - it can also expand on a wide range of actions: confirmation check or clarification request, for example. Any kind of action that attempts to clarify, correct, notice, confirm or check an utterance either by the speaker himself or his counterpart becomes a repair. It also adopts afffiiative repairable forms (ways to mitigate negative effects) and less frequent disaffiliate and direct negative evaluation (Seedhouse, 2004). Extract 3 is used to capture some other images of identity in interaction as a support the search of what makes a teacher.

S5 starts with a hesitant discourse marker 'er' followed by a 0.1 second pause before being able to accomplish the first part of the interactional requirement. It is characterised by a linguistic misuse of the word 'what' that is then followed by another hesitant discourse marker 'er'' and an even longer 0.3 second pause plus more hesitation 'er' and another 0.3 second pause before succeeding with her turn (54 & 55). The number of pauses plus the hesitation markers reveal that there is a linguistically rather than communicative embedded purpose. Although there are noticeable sources of trouble neither S6, who nominates herself as the next speaker, nor the teacher accounts for the problems and consequentiy no repair is undertaken. What comes then is S6 keeping the flow of the conversation going and responding appropriately to her counterparts enquiry in spile of the 0.5 second pause that displays an image of an embedded form and accurate utterance rather than a turn for the negotiation of meaning (turn 56). S6 is interrupted by the teacher in turn 57 who identifies a source of linguistic trouble, the lack of the preposition 'to' and supplies a correct version of the linguistic forms (Seedhouse, 2004: 166) and repairs it using one of the trajectories - other-initiated other-repair -. S6 completes her turns (58 - 61) and adds some more information although hesitation is displayed through word repetition 'and and', L1 use, extended recurrent pauses - 0.4, 0.5, 0.8 and 0.4 -, hesitation markers 'er' uttered three times. There are also noticeable accuracy gaps such as French, big, on and climb, plus a repairable feature of pronunciation - [kllmb].

The teacher allocates some time for S6 to accomplish the interactional enquiry and even some repairable issues that emerged were simply categorised as 'let them pass' (sources of trouble where no repair is undertaken). The teacher first mitigates the effects of negative feedback and starts through an affiliative discourse marker 'yes'and then re-phrases S6 contribution in more accurate words (turns 63 - 64) and also extends it (turn 65). The teachers repair is acknowledged by S6 through an affiliative discourse marker, 'yeah'(turn 66). The teacher then creates an opportunity for language use and enquiries for more information in the form of a request for clarification 'withyour friends'!'(turn 67) which is confirmed, 'yeah', by S6 (turn 68). The teacher then changes the talk direction and formulates a question to S5 who has been chosen as the next speaker (turn 69). S5 assumes the load of the conversation and answers 'no I didnt' (turn 70). The teacher nominates herself as the next speaker and rephrases S5s contribution through a confirmation check 'you didnt' and adds some more information that works as an opportunity to keep the flow of the conversation going (turns 71 & 72). The teacher allocates the turn to S5 who responds straight away in a more communicative oriented attempt 'no, I spend' but as she notices that her answer has to follow the rules already established by the teacher, she then takes a 0.4 second pause to re-shape her contribution towards ' used to '(turns 73 & 74). It also works as a repair in the form of a self-initiated self-repair trajectory. S5 holds the floor and expands on more illustrative information through the use of the conjunction 'or' followed by a hesitant discourse marker 'er' and a 0.5 second pause taken as a gap to accommodate her talk to the form and accuracy context. S5s utterance fits into the sequence although the restriction imposed does not contribute much to responding fluently (look at the hesitance marker 'emm' and the 0.3 second pause displayed in turn 75). Turns 76 and 77 also display another discourse marker 'er' and then a self-initiated self-repair trajectory. She notices the source of trouble, repairs it herself and carries on with the load of the conversation. Turn 77 displays another source of trouble (the article ' the' and 'Mad')both successfully repaired at the end of it. It is characterised as a self-initiated self-repair trajectory. T evaluates S5 contribution with an affiliative discourse marker good (turn 78).

Although repair has been generally categorised as one of the most frequent actions that teachers undertake in the language classroom, its organisation varies according to the pedagogical focus (van Lier, 1988a). The data show that one of the distinctive roles played by the teacher is concerned with repair as a varied approach that includes error correction (turn 57), confirmation check (turns 63 - 65 & 71 and 72) or clarification request (turn 67) . Although the self-initiated self-repair trajectory appears to be one of the most common repairable actions (see turns 73 - 77), the teacher considers repair as part of her teaching goal, although what is judged as worthy of repair is not evident or easy to categorise. While turns 57 - 62 display varied sources of linguistic trouble, the teacher lets them pass while a lack of the preposition 'to'(turn 56) is considered as repairable.

The teacher is the one in charge of repairing (See turns 57, 63 - 65,67, and 71 & 72). There is no any sign of student-student repair, for example. There is an interesting image of teacher identity in the form of pedagogical mitigation of the negative effects of correction. Even problematic utterances (turns 58 - 61) are positively acknowledged (turns 63 - 65) and there is a clear affiliative purpose towards creating learning atmospheres. It may also explain why the pedagogical strategy of let it pass has clear effects on facilitating rather than impeding commumcation. Seedhouse (2004) concluded from the analysis of classroom data that negative evaluation is rarely manifested, which also seems to be confirmed while looking at extract 3 in this study.

Conclusion

Relevant images of the way teacher professional identities are co-constructed and shaped through their interactions were revealed in the analysis of classroom talk in this study. There is a figure of asymmetric interaction that empowers the role of the teacher as dominant over students. She asks the questions, pre-allocates turns and holds the floor to ensure pedagogic control. A model of interaction based on a teacher-student structure is prevalent with no forms of student-student variation, for example. Students normally respond to the teachers enquiries and rarely adopt a more proactive role. Although the IRF/E cycle is claimed to be a characteristic of a traditional teacher-centred classroom, it was a prevalent pedagogic move in the context of the study. The teacher assumes half of the communicative turns which are based on a question-answer sequential system. Repair assumes the form of error correction mainly with no clear intention to let some of them pass while in some other situations some errors are categorised as repairable by the teacher. Some other forms of repair such as clarification request or confirmation check appeared occasionally and their effects on learning seem to be more profitable than the correction of errors.

By exploring some of the sequential organisation and structure of the conversational exchange system, its pedagogical function or interactants implicit ascription to mstitutionally embedded rules of interaction, some issues of TI can be addressed with the intention of gaining a closer understanding of what makes a teacher. This study claimed that CA helps in the attempt to uncover part of the nature of teacher professional identity as a construct that is constituted in discourse. This was an early and located exploration of a field of research and/or theoretical consideration that is still under construction with permanent and controversial new issues for its own re-conceptualisation. Some new insights of TI that could be analysed from a context different to the classroom, in informal conversations with students, colleagues, parents or principals arise as an orientation for future research.

References

Ball, S. J. (1972). Self and identity in the context of deviance: the case of criminal abortion. In R Scott & Douglas, J. (Eds.), Theoretical perspectives on deviance. New York, Basic Books.

Ball, S. J. & Goodson, I. (1985). Teachers lives and careers. Lewes, Falmer Press.

Bellack, A. A., KUebard, H. M., Hyman, R. T. (1966). The language of the classroom. New York, Teachers College Press.

Benwell, B. & Stokoe, E. (2007). Discourse and Identity. Edinburgh, Edinburgh University Press.

Buzzelli, C. A. & Johnston, B. (2001). Authority, power, and morality in classroom discourse. Teaching and Teacher Education. N° 17, pp. 83-84.

Cooley, C. H. (1902). Human nature and the social order. New York, Scribner.

Cooper, K., & Olson, M. (1996). The multiple Ts of teacher identity. In M. Kompft, I, et. al. (Eds.) Changing research and practice: teachers professionalism, identities and knowledge. London, Falmer Press.

Cullen, R. (2002). Supportive teacher talk the importance of the F-move. ELT Journal. N° 56(2), pp. 179-187.

Day, C. (2004). Passion for teaching. London, Routledge-Falmer.

Day, C, Kington, A., Stobart, G., Sammons, P. (2006). The personal and professional selves of teachers: stable and unstable identities. British Educational Research Journal. N° 32(4), pp. 601- 616.

Edwards, A., & Westgate, D. (1994). Investigating classroom talk. London, Falmer Press.

Goffman, E. (1959). The presentation of self in everyday life. New York, Doubleday.

Goodson, I. E, & Hargreaves, A. (1996). Teachers professional lives. London, Falmer Press.

Hall, J. K., & Walsh, M. (2002). Teacher-student interaction and language learning. Applied Linguistics. N° 21(3), pp. 376-406.

Hargreaves, A. (1994). Changing teachers, changing times. London, Falmer Press.

Hargreaves, A. (1998). The emotional practice of teaching. Teaching and Teacher Education. N° 14(8), pp. 835-854.

Hargreaves, A. (2001). Emotional geographies of teaching. Teachers College Record. N° 103(6), pp. 1056-1080.

Heritage, J. (2005). Conversational Analysis and Institutional talk. In K. L. S, Fitch (Eds), Handbook of language and social interaction. Mahwah, Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, inc.

James-Wilson, S. (2001). The influence of ethnocultural identity on emotions and teaching. Annual Meeting of the American Educational Research Association. New Orleans.

Johnson, K. F. (1995). Understanding Communication in Second Language Classroom. Cambridge, Cambridge University Press.

Kasper, G. (2001) Four perspectives on L2 pragmatic development. Applied Linguistics. N° 22, pp. 502-530.

Kelchtermans, G. (1993). Getting the story, understanding the lives: from career stories to teachers professional development. Teaching and Teacher Education. N° 9(5/6), pp. 443-456.

McCarthy, M., & Walsh, S. (2003). Discourse. In Nunan, D. (Eds.), Practical English Language Teaching. San Francisco, McGraw-Hill.

Mead, G. H. (1934). Mind, self and society. Chicago, University of Chicago Press.

Nias, J. (1989). Primary teachers talking. London, Routledge & Kegan Paul.

Nias, J. (1996). Thinking about feeling: the emotions in teaching. Cambridge Journal of Education. N° 26(3), pp. 293-306.

Pike, K. (1967). Language in relation to a unified theory of the structure of human behaviour. The Hague, Mouton.

Richards, K. (2006). Being the teacher: Identity and classroom conversation. Applied linguistics. N° 27(1), pp. 51-77.

Schegloff, E. A. & Sacks, H. (1973). Opening up closings. Semiotic. N° 7, pp. 289-327.

Schegloff, E. A. (2000a). Overlapping talk and the organization of turn-taking for conversation. Language in Society. N° 29, pp. 1-63.

Schegloff, E. A., Koshik, I., Jacoby, S., & Olsher, D. (2002). Conversation Analysis and Applied Linguistics. Annual review of Applied Linguistics. N° 22, pp. 3-31.

Seedhouse, P. (2004). The interactional architecture of the language classroom: A Conversation Analysis perspective. London, Blackwell.

Sikes, P. J., & Measor, L. W. (1985). Teacher careers: crisis and continuities. Lewes, Falmer Press.

Sinclair, J. M., & Coulthard, M. (1975). Towards an analysis of discourse. Oxford, Oxford University Press.

Sleegers, P., & Kelchtermans, G. (1999) Professional identity of teachers. Pedagogisch Tijdschrift. N° 24, pp. 369-374.

Sumsion, J. (2002). Becoming, being and unbecoming an early chidhood educator: a phenomenological case study of teacher attrition. Teaching and Teacher Education. N° 18, pp. 869-885.

Sutton, R. E. (2000). The emotional experiences of teachers. The Annual Meeting of the American Educational Research Association. New Orleans.

Van Lier, L (1988a). The classroom and the language learner. New York, Longman

Van Lier, L. (1988b). Whats wrong with classroom talk?. Prospect. N° 3, pp. 267-283.

Van Lier, L. (1996). Interaction in the Language Curriculum. London, Longman.

Van Veen, K., & Sleegers, P. (2005). How does it feel? Teachers emotions in a context of change. Journal of Curriculum Studies. N° 37, pp. 85-111.

Walsh, S. (2002). Construction or obstruction: Teacher talk and learner involvement in the EEL classroom. ELT Journal. N° 62(4), pp. 366-374.

Walsh, S. (2006). Investigating Classroom Discourse. Abingdon, Roudedge.

Zembylas, M. (2003). Emotions and teacher identity: a post-structural perspective. Teachers and Teaching. N° 9(3), pp. 213-238.

Appendix