Language policies are usually established to ensure that the citizens of a country can speak an additional language. In the case of Colombia, emphasis is placed on learning English. According to Colombia’s current language policy, 30% of university students are expected to achieve B1 and 25% to achieve B2 of the Common European Framework of Reference for Languages (Ministry of National Education, 2014). However, this goal is yet to be achieved, with “23% achieving B1 and 11% B2” (Icfes Saber Pro, 2021, p. 108). In fact, the level of English among students has remained unsatisfactory throughout the last decade (Benavides, 2021). Moreover, research indicates that students are far from reaching this goal (Alonso et al., 2018). In the specific context of the South Colombian University (USCO), the aims of this policy are yet to be fully met, with 28% of students at B1 and 8% at B2 (Icfes Saber Pro, 2021). A curriculum assessment is one means of discovering why students are failing to meet policy aims. The starting point is a needs analysis (NA), which helps to determine the issues affecting the courses and limiting their success (Macalister & Nation, 2020). NAs also serve as an opportunity for stakeholders to communicate priorities among themselves. This was the purpose of this study: to conduct an NA in the context of compulsory English courses at USCO.

This paper seeks to contribute potential answers to the ongoing questions of what to teach and how to teach English in Colombia. Ever since English became the target language in the 1980s, developing a functioning system has remained a challenge for the country (Cárdenas, 2018). One issue was overlooking the significance of conducting NA. This has prompted contradictory language policies, dissatisfaction across stakeholders, and misuse of resources (Miranda & Valencia, 2019). In the specific context of USCO’s compulsory English courses, an NA had never taken place. This was a factor in undertaking this study. Its results will be shared with policy makers, curriculum writers, and language teachers. This study research questions were as follows:

- What are the disfavouring conditions that teachers consider to be affecting the compulsory English courses?

- What is the gap, if any, between the English language training that current and former students receive at USCO and their felt needs for the future?

- What are the suggestions from current and former students, teachers, and the supervisor for improving the compulsory English courses at USCO?

Literature Review

English for General Purposes and English for Specific Purposes

Compulsory English courses at universities tend to either follow an English for General Purposes Approach (EGP) or an English for Specific Purposes Approach (ESP). Based on Viana et al. (2018), EGP involves the learning of English without any specific use prioritised. Its focus is generally on student proficiency, that is to say, the development of their general communicative ability. When following EGP, students are not usually consulted as to why they are learning English. Decisions are already made by other stakeholders before students arrive in the classroom. Those stakeholders may be the government, the educational institution itself, the textbook, teachers, or others. In contrast, when following ESP, students, who are usually older, are acknowledged as essential stakeholders who are aware of their reasons for studying English. These reasons are explained to teachers, who act as facilitators to reach those goals (Hutchinson & Waters, 1987). The defining feature of ESP is that its teaching design and materials are founded on the results of an NA (Dudley-Evans, 2001). As a result, courses are shaped by students’ English needs, as well as by the skills they require English for.

Needs Analysis

The concept of need analysis can be traced back to the 1920s, yet it was not until the 1970s that they became widely used as an essential step towards language course-planning (Brindley, 1989; West, 1994). Demand followed the transition from general course design to a more specific structure, one that catered for the language needs of students from various academic fields (Schutz & Derwing, 1981). However, this is not to say that a general course does not require an NA. In fact, the lack of an NA could limit the course overall success.

Approaches to Needs Analysis

The approach to NAs depends on how the concept of needs is understood. As a result, different approaches have been developed over time. Brindley (1989) considered two approaches: product-oriented and process-oriented. The former related to the learners’ needs in terms of the language proficiency required to perform in a specific scenario. The latter considered the affective and cognitive variables that affect learning, e.g., self-confidence, motivation, anxiety, etc. On the one hand, a product-oriented approach framed needs as objective, for instance, as academic benchmarks that students were required to attain. On the other hand, a process-oriented approach framed needs as subjective, referring to the cognitive and affective conditions necessary for learning, e.g., teachers’ support, a positive learning environment. Alternatively, Berwick (1989) considered two kinds of needs: felt and perceived. The former related to a learner’s desired future state, e.g., speaking a language fluently, performing academic tasks in a different language, etc. The latter referred to desired standards set by experts or tests, e.g., a mark on the TOEFL, IELTS, or university entrance examination.

Almost a decade later, Dudley-Evans and St. John (1998) delivered three types of NAs: Target Situation Analysis (TSA), Learning Situation Analysis (LSA), and Present Situation Analysis (PSA). For this paper, an LSA approach was selected, as shown in table 1. Said approach involves exploring subjective, felt, and process-oriented needs. These all concern the cognitive and affective factors that affect learners when studying a foreign language (Brindley 1989; Berwick, 1989). In the context of this study, an LSA identified the felt needs of current and former students, answering the second research question.

Table 1

Three Types of Needs Analysis based on Dudley-Evans and St. John (1998)

|

TSA

|

LSA

|

PSA

|

|

Objective, perceived, and product-oriented needs.

|

Subjective, felt, and process-oriented needs.

|

Strengths and weaknesses in language, skills, and learning experiences.

|

Situation Analysis

NAs usually require an additional dimension which acknowledges the disfavouring conditions of a specific context. This extension to NAs is also known as means analysis (Brown, 2009), environmental analysis (Macalister & Nation, 2020), or situation analysis (Richards, 2017). Even when choosing the appropriate NA approach, as well as when collecting valuable information, these could be deemed premature without recognizing the contextual difficulties that face a given English class. Possible constraints for teachers include inadequacy of syllabuses, administrative attitudes towards second/foreign language teaching and learning, accessibility of resources or lack thereof, class size, government language policies, availability of time for NAs, and others (Pennington & Richards, 2016). This NA study aimed to identify disfavouring conditions that impede the implementation of an appropriate curriculum.

Empirical Studies

There is overall agreement that student needs and interests—usually related to their field of study—should form the cornerstone of English university courses, because many students are expected to perform future work in English (Arias-Contreras & Moore, 2022; Castillo & Pineda-Puerta, 2016; Garcia-Ponce, 2020). Employers have a fixed idea of the tasks that graduates should be able to perform in English, including writing emails, delivering presentations, interacting with native speakers, networking, and dealing with suppliers/costumers. Nevertheless, the list varies depending on the profession. Health professionals, for example, are expected to have a thorough understanding of medical terminology, as well as to communicate effectively with patients and colleagues (Pradana et al., 2022). Even professions such as agricultural workers, for whom English may not at first glance be a priority, are now required to read and speak in English in their jobs (Arias-Contreras & Moore, 2022). The reality, however, is that English university courses fail to meet these expectations.

The literature provides several possible explanations of this fact. Firstly, the courses follow EGP instead of ESP. By choosing EGP, focus is placed on providing the learner with general grammar and vocabulary. This approach is believed to be dominant in higher education because of disfavouring conditions. English courses at university tend to have a low number of class hours, usually between 2 and 4 hours per week, instead of 6 or 8 (Mosquera, 2022). Courses are usually founded to comply with governmental language policies, and, as a result, follow a standardized syllabus and textbook, limiting teacher autonomy (Arias-Contreras & Moore, 2022). Moreover, student proficiency is sometimes so low that employing ESP is not feasible (Arias-Contreras & Moore, 2022; Said & Herlina, 2022). Even when teachers receive the appropriate training for ESP, universities may have a shortage of resources, hindering their performance (Sánchez et al., 2017). Therefore, despite preferring ESP, teachers tend to revert to EGP (Poedjiastutie & Oliver, 2017; Pradana et al., 2022).

To ensure a successful transition to ESP, it is necessary to overcome certain issues among stakeholders. In the case of students, there is a conflict between short-term and long-term expectations (Li & Heron, 2021). On the one hand, they are keen to pass compulsory English courses as soon as possible to focus on other areas of study. However, they are also aware of the impact of English on career prospects. This results in a dilemma for students: whether to focus on their chosen field or on their English courses (Mosquera, 2022; Trujeque-Moreno et al., 2021). There are also issues to overcome in terms of course administrators. University goals, for example, in equipping students for the future of international research, may not align with course content (Garcia-Ponce et al., 2021). Awarding an international qualification upon completion such as the TOEFL is one possible solution (Sánchez et al., 2017). An additional solution is to employ alternative approaches, allowing the two EGP and ESP to blend (Harper & Widodo, 2018). Teachers, despite contextual constraints, are urged to select materials that align with the principles of ESP. This can mean departing from a given English textbook (Nuñez, 2018; Salamanca, 2020).

Methods

Procedure for Needs Analysis

This NA had a case study as its approach. Case studies involve an investigator or analyst exploring a real-life, contemporary bounded system (a case) or multiple bounded systems (cases) over time (Creswell & Poth, 2018). For this paper, the case was the compulsory English courses at USCO. This methodology was selected as it provides researchers with opportunities to explore or describe an event in context through multiple outlooks, leading to the discovery of new information as the study advances (Schwandt & Gates, 2018). In an exploratory case study, participants are seen as sources of information, and contribute to the understanding of a problem.

This NA took place at a state university located in the south of Colombia. The university offers 32 undergraduate programmes and, according to University Agreement 065 of 2009, all students must complete the compulsory English courses to be eligible for graduation (Consejo Superior de la Universidad Surcolombiana, 2009). Those enrolled in teaching programmes are required to take six courses, while those enrolled in non-teaching programmes are required to take four. In addition, the compulsory English courses for teaching degrees grant two academic credits, while non-teaching degrees do not. This means that the marks that non-teaching degrees students receive in their courses will not count towards their Grade Point Average. These courses are mainly concerned with developing students’ four language skills: speaking, writing, listening, and reading. This also includes a component in grammar and vocabulary. When selecting participants, a broad range of stakeholders was prioritised. Previous research carried out in the same context involved only student participants (Jaime & Coronado, 2018; Zúñiga et al., 2009). This study, consequently, recruited different stakeholders, including current and former students, teachers, and the supervisor.

Participants were recruited in two different ways. First, access to teachers was granted by the supervisor, who provided a list of 24 teachers with their emails attached. All 24 teachers were sent an invitation over email to participate in the study, with five responding. A total of four teachers agreed to participate in both the questionnaire and the interview. Only one of them chose to participate exclusively in the questionnaire. Second, current and former students were recruited through chain sampling (Patton, 2015). A Google Form link was sent with the survey to a pair of current and former students, acquaintances of the researcher, who then shared it on social media platforms. In the questionnaire, students could choose to leave their email if they wished to participate in an interview (see table 2). In total, 25 students responded the questionnaire: 12 current students and 13 former students. Five of these students decided to participate in the interview: two current students and three former students (see table 2). The supervisor was invited to participate in an interview during the latter stages of the data collection process.

Table 2

Study Participants

|

Instruments

|

Current students

|

Former students

|

Teachers

|

Supervisor

|

|

Number of questionnaires completed

|

12

|

13

|

5

|

Not Applicable

|

|

Number of interviews completed

|

2

|

3

|

4

|

1

|

Questionnaires

Data was initially collected through a questionnaire consisting of 19 questions. Three versions of this questionnaire were designed, fitting the profile of each group of participants. All questions were structured, except for the final question which was open-ended. The questions were generated using Rossett’s model (1982). The model generates five types of questions:

- problems, which lead to the identification of a problem/problems.

- priorities, which are used to judge more urgent needs.

- abilities, which test the knowledge or skills that learners are expected to have.

- attitudes, which determine the emotions or perspectives held by the learners.

- solutions, which shed light to possible routes to deal with the problem.

Some questions were also designed following the literature review about needs analysis in higher education in Colombia (Castillo & Pineda, 2016), which indicated that students tend to prefer ESP over EGP. The list of possible felt needs, used in question 15, was adapted from Gómez (2017). They were chosen to form a list of the most likely needs felt by students.

Interviews

A total of ten interviews took place, each lasting 30-35 minutes. Interviews were arranged online and recorded with the consent of participants. A semi-structured interview format was chosen, since it allows the interviewer to use different types of questions, such as follow-ups, probing, and indirect questions. This allows for greater discussion of themes and issues (Brinkmann & Kvale, 2018). Three broad questions were drafted in advance of interviews, but these were not compulsory; rather, they worked as a reminder of which issues were necessary to cover (Thomas, 2021).

Data Analysis

NA results were analysed using a constant comparison method. Questionnaire answers were displayed as infographics, and interviews were transcribed verbatim. The research questions were used as a framework to analyse and interpret the data. This included grouping the questions directly relating to the research questions, eliciting themes and follow-up questions for interviews.

The constant comparative method as laid out in Thomas (2021) is as follows. The process involves:

- Reading the transcripts, listening to recordings, and viewing the questionnaires infographics.

- Creating two different files: one in which the data was kept safe and uncorrupted, and another to be highlighted and commented upon.

- Prior first reading: assigning three different colours to cues that could lead to answer the research questions.

- Creating a list of recurring subjects or ideas. These ideas are known as temporary constructs.

- Prior second reading: highlighting counterexamples, if any, in different colours.

- After second reading: creating a list of second-order constructs, that is, constructs that were mentioned frequently, representing important themes in the data.

- Organising second-order constructs into themes.

- Establishing connections between themes in terms of both concordances and contradictions.

- Mapping themes.

- Selecting representative quotations to illustrate these themes.

Results

Disfavouring Conditions Affecting the Compulsory English Courses

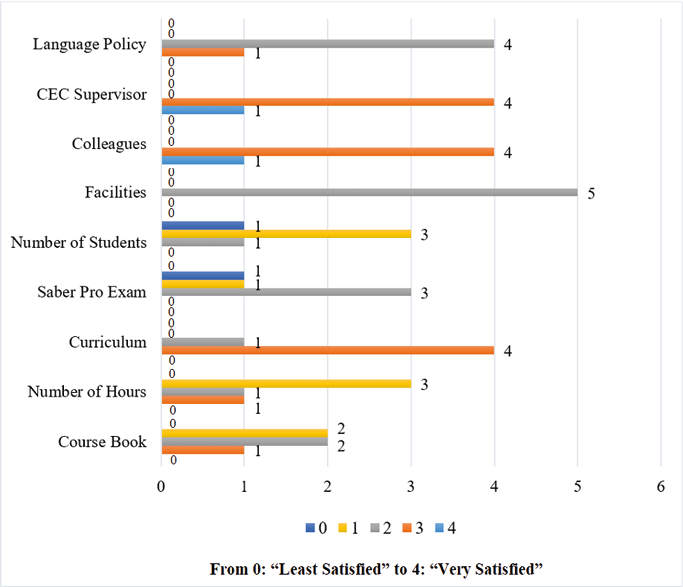

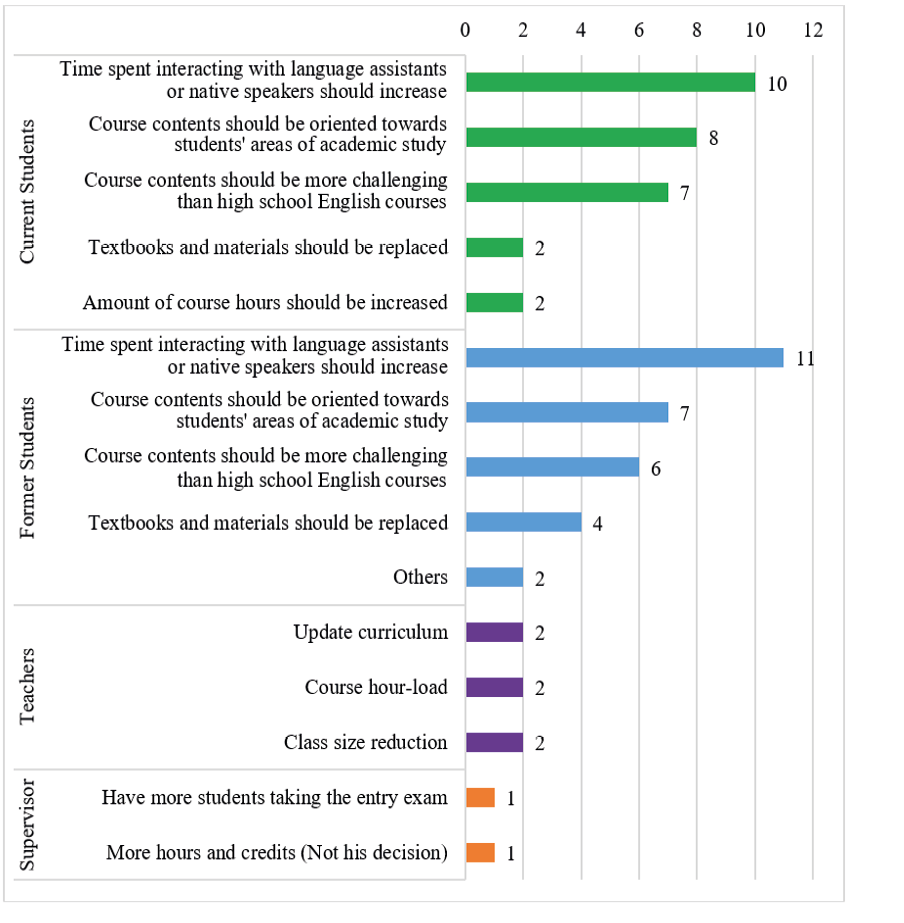

In the questionnaire, teachers were asked to rate their level of satisfaction regarding different aspects linked to the Compulsory English Courses. Figure 1 shows the frequency with which each option was chosen. Facilities and the number of students in the classroom were the aspects that teachers were the least satisfied with. This was later confirmed in interviews, where all four teachers referred to the challenges of seating up to 45 students in classrooms intended to fit 25 to 30. Those challenges included issues with classroom management, cheating during assessment, and limited opportunities for feedback. Large number of students also pose a challenge for university facilities, triggering other issues, such as shortage of chairs, lack of personal space, and overheated air conditioning. These all contribute to disfavouring conditions which affected both teachers’ performance and their attitude towards the class. In one teacher interview, a teacher claimed: “The moment I arrived in the classroom, I have to say it put me off: the heat [was significant], [there were] students everywhere.” Furthermore, in interviews, all teachers indicated that assessment was the aspect of their practice that was most affected. One of the teachers stated: “It was just so stressful to find ways in which assessment could be done properly.” With exams expected to be paper-based and in-person, teachers needed to be resourceful and implement different strategies, including “splitting the class into two groups, schedul[ing] them for different days, and then do[ing] the same for the speaking test.” Despite these strategies, teachers remained unconvinced. They were aware of many of the problems associated with assessment, including cheating.

The second disfavouring condition was the textbook, American Channel, in use since the courses were first introduced in 2009. This is based on questionnaire answers in which four out of five teachers stated that they held mixed views: two were dissatisfied and two neither satisfied nor dissatisfied (figure 1). Teachers stated their dissatisfaction with and lack of enthusiasm for a textbook which had been used for over a decade. This results in numerous problems one being cheating as one of the teachers states: “After finishing one course students would share the content and the answers from the textbook with new students.” Teaching would be affected as a result, as teachers could not rely on grammar tests or activities from the textbook to which students already knew the answers. This would increase their workload, as it would be necessary to create and/or seek new materials regularly. Students, furthermore, would be disinclined to purchase the textbook. The most challenging aspect for teachers, however, was the outdated nature of the textbook content. As one of the teachers explained in their interview: “The textbook is outdated: it even talks about cassettes. The unit topics are no longer suitable for students this age.” Opposition against the textbook was further evidenced in the open-ended questions in which teachers were asked to give their opinions on possible improvements to the Compulsory English Courses, with one teacher stating: “Change the textbook, it is completely obsolete.”

The final disfavouring condition that teachers raised during interviews was the lack of cohesion between colleagues, the supervisor, and the English Teaching Department. Despite the fact that both colleagues and the supervisor were rated positively in the questionnaire, with teachers marking either satisfied or very satisfied (figure 1), teachers also called for a greater sense of teamwork during interviews. With staff meetings taking place exclusively at the start and end of the semester, teachers hold that there is usually no opportunity to share the progress of their courses or to exchange ideas among colleagues during term-time. As a result, teachers felt that they had no one to speak to when they faced difficulties in their class, or, more positively, to share knowledge or strategies. One teacher said: “I wish they [supervisor/English Teaching Department] would ask me ‘How are things? Have you run into any issues?’ But no. There’s one meeting at the start [and] one at the end. That’s all.” Most important, teachers felt, was the lack of opportunity to knowledge exchange between colleagues. As stated in different interviews, even when a group of teachers delivered the same course level, each would do so independently from their fellow colleagues. This represented a missed opportunity to collaborate as one teacher stated that their colleagues “create[d] some wonderful activities—actually brilliant ideas—but we never [got] to hear them.” As a result, teachers requested a bottom-up approach, in which staff could communicate with each other more often, including meetings in which they could speak with the supervisor and other members of the English Teaching Department.

Figure 1

Teachers’ Satisfaction Regarding the Courses. Scale from “0—Least Satisfied” to “4—Very Satisfied”

Gap between the English Language Training of Current and Former Students and their Felt Needs for the Future

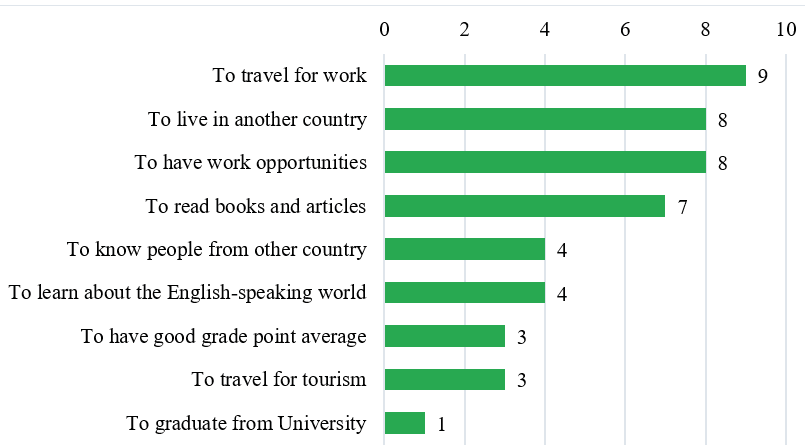

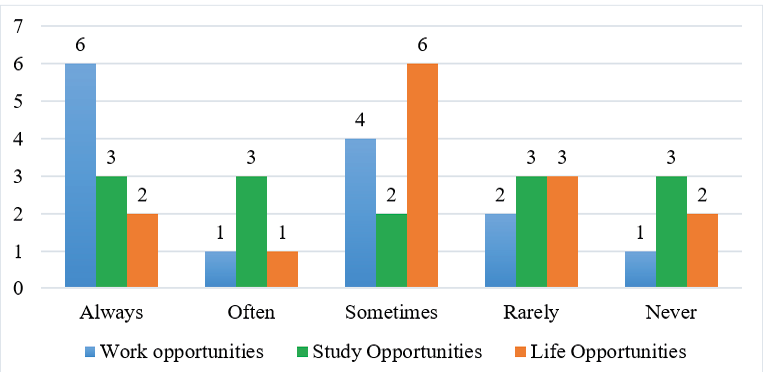

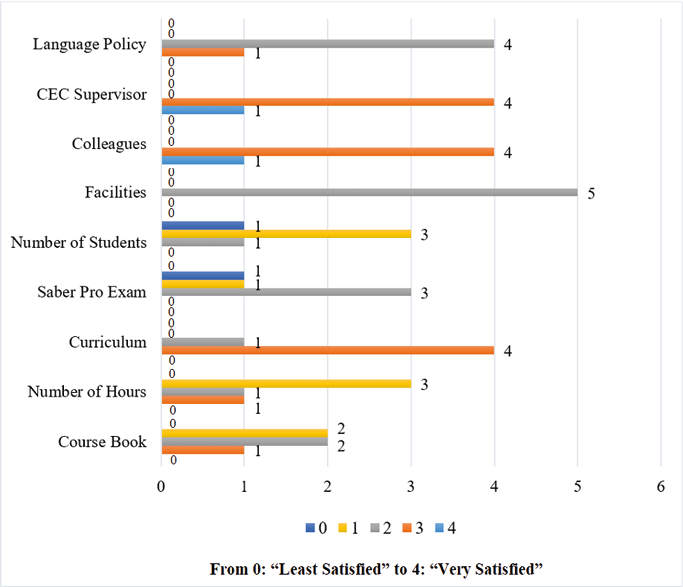

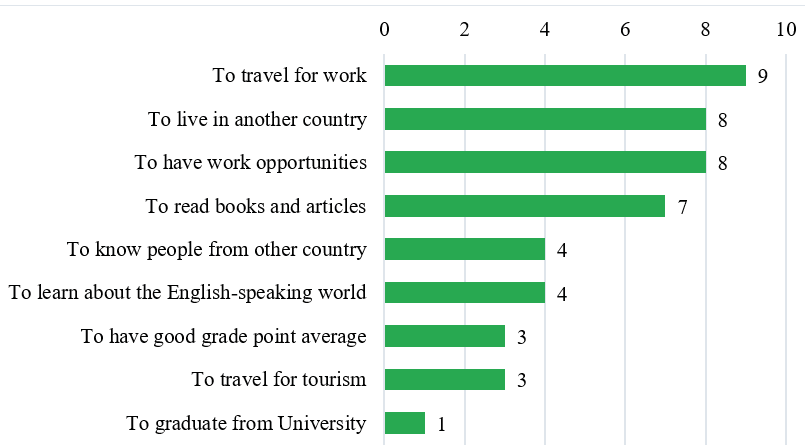

From the questionnaires and interviews with former and current students, the desire to go abroad is the most expressed felt need. Most students believe that English will provide them with better job opportunities abroad. In the questionnaires, “I take English courses to travel abroad for work” was the most popular reason for current students to take the courses with nine out of thirteen votes (figure 2). Students’ main motivation for seeking work abroad is increased income. This was the case of a current student on her last year of university who was applying to work as an au pair in the USA. She remained, however, concerned as to the proficiency of her English. She explained: “I wish I could have had more lessons to practice my spoken English, to prepare myself for this challenge.” Regarding former students, six out of thirteen students claimed to always lose job opportunities due to their level of English (figure 3). During interviews, students recalled their frustration at job interviews. They were often unable to answer in English when called upon to do so. Given that ESP is intended to address students’ needs, it can therefore be assumed that both current and former students would prefer it over EGP classes.

As well as using English as a tool to generate more job opportunities, both current and former students also attempt to use English in academic settings. Current students who were in their last year of university, either writing their dissertations or research papers, were well-aware of the advantages of English reading skills. “If you go on databases, you’ll find thousands of articles in English, in comparison with just a few in Spanish,” said one final-year university student. In the case of former students who continue to be involved in academia, they spoke of the difficulties of publishing their work due to limited English writing skills. A former student, completing her master’s degree, described her desire to write in academic English: “If you are able to write in English, you can save yourself huge amounts of money on translation, as well increasing your chances of publishing your work in high quality journals.” The advantages of increased academic English writing skills also include enrolling in PhD programmes abroad. Being able to speak English, they said, “is both mandatory in most PhDs programmes, but also an advantage when applying for scholarships”.

Figure 2

Current Students’ Felt Needs

Figure 3

Level of Frequency Former Students Lose Opportunities Due to Their Level of English

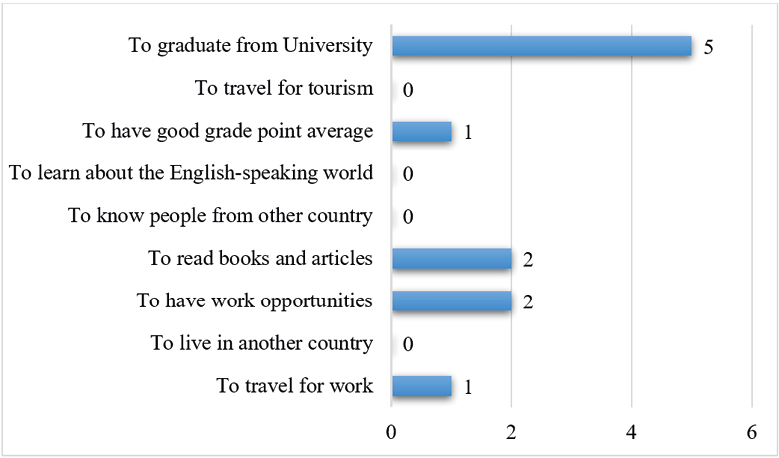

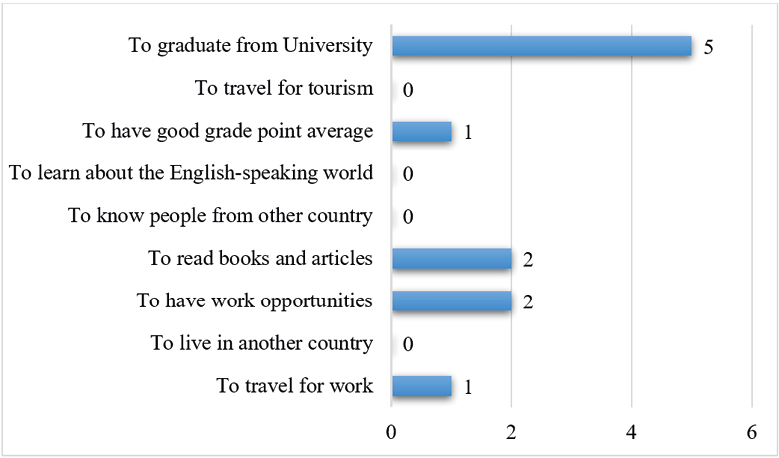

The gap, therefore, consists of the following: most students would prefer ESP, but the materials and content of the compulsory English courses at USCO follow EGP. Further confirmation of this gap comes from the teachers’ questionnaire results, where teachers selected “to graduate from university” as the most popular reason as to why their students take the courses (figure 4). This could indicate a lack of awareness as to students’ felt needs on the part of teachers. The issue with following EGP instead of ESP is that, according to former and current students, both commented that the university courses resembled the courses they took in secondary education, rather than representing a further challenge: “I feel that nothing [had] really changed. They were even teaching me numbers, colours, the verb to be. I mean, come on!” This was said to be the content of the textbook American Channel, which was heavily criticised by both former and current students, as well as by teachers. Students argued the content of American Channel was uninteresting. The fact that the textbook has been used for over ten years added to students’ lack of interest. Moreover, cohorts of students go through the same materials each semester. To conclude, students want a course that contributes to their academic and professional training. This, however, is yet to be delivered by an outdated EGP course.

Figure 4

Teachers’ Results to the Statement “My students take the English courses to…”

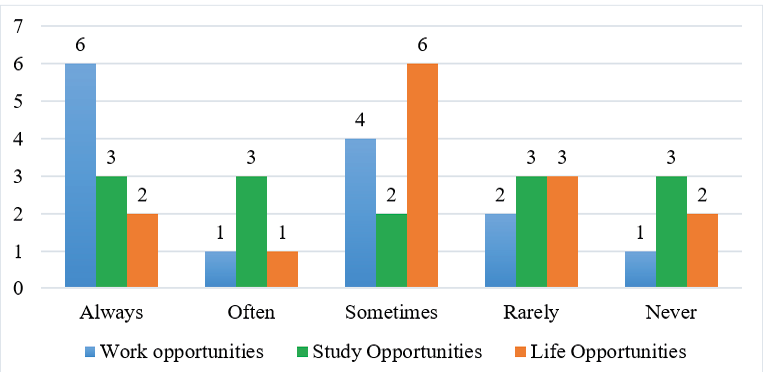

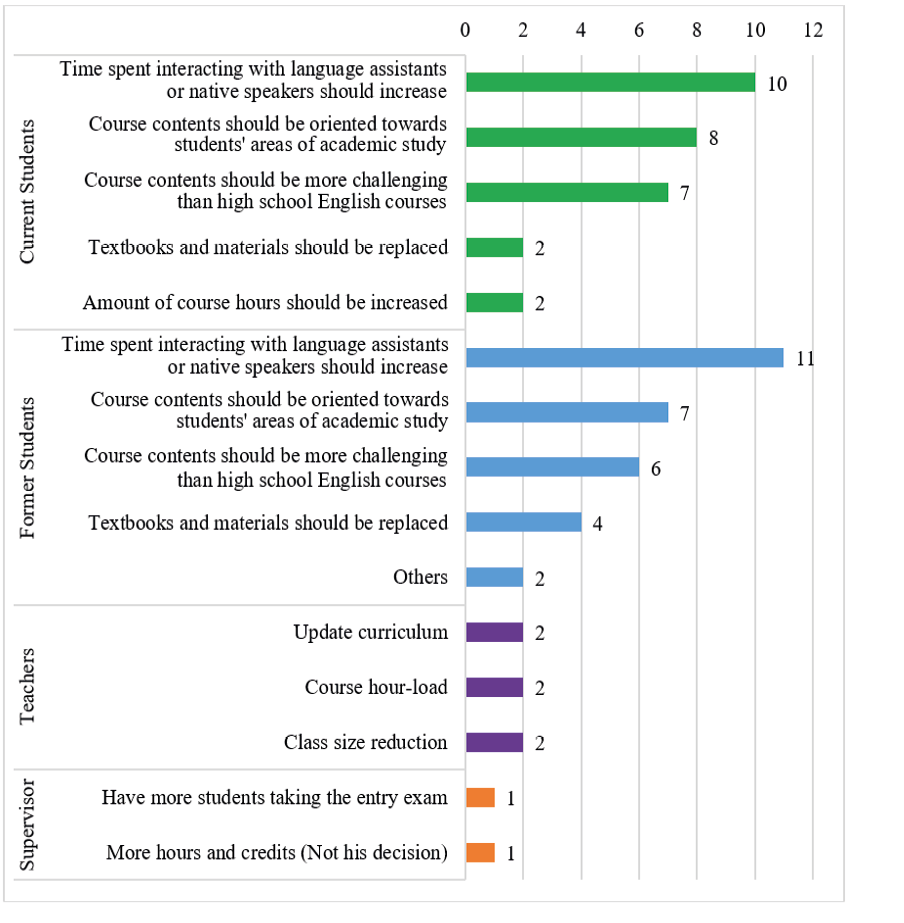

Suggestions for the Improvement of the Compulsory English Courses: From the Perspective of Current Students, Former Students, Teachers, and the Supervisor

In both interviews and questionnaires, participants were unanimous in their suggestions for improvement to the Compulsory English Courses at USCO: decrease class size, increase classroom resources, and change textbook. However, some unexpected responses are given below.

Both groups of students requested the best available teachers, which would require the assessment of teachers’ level of English. Current and former students called into question the English language proficiency of some teachers. To improve the courses, they believed, it is necessary to assess teacher’s English proficiency as well as their pedagogical skills. One current student argued that teachers should be “assess[ed on] the knowledge that they have too. We’d know how skilled and how resourceful they are.” Another former student said: “I also think it is important to have bicultural teachers... Sometimes you hear teachers speaking as badly as students do. Their teaching profile has to be [higher].” This may also explain the choice of “the interaction with native speakers should be increased” as the most popular way of improvement among both groups of students (figure 5). Students argued that it could be useful and more motivating to have someone who speak English as their mother tongue, which might also provide information on cultural aspects of the language.

In terms of management of courses and collaboration between teachers, the following changes were suggested by teachers. First, they believe the university should enact a curriculum reformation in which the compulsory English courses grant academic credits to all undergraduate degrees, regardless of whether they are teaching degrees or non-teaching degrees. By adding credits, the marks students receive from the courses would impact their Grade Point Average. Students would therefore feel more motivated to deliver a better performance. In addition to adding credits, teachers feel that it would be helpful to update the English courses curriculum. Two significant changes would be additional course hours for English and updating the content to target students felt needs, i.e., desire to use English in professional and academic settings. To do so, teachers requested a greater number of teacher meetings and catch-ups with their supervisor. However, they stressed the importance of payment for these additional hours. In the words of one teacher: “We get together to design exams but not to plan the syllabus. Sometimes we don’t know, for example, when teachers are doing wonderful things in their lessons. It is all about sharing knowledge”.

The supervisor suggested launching awareness campaigns amongst students on the value of learning English. He also stated his belief that students from all undergraduate degrees should be granted academic credits upon completion of their English courses. The supervisor, however, stated that the addition of credits is unlikely to occur, as each faculty makes autonomous decisions in terms of their academic credits (figure 5). Adding credits to the compulsory English courses would require significant changes to the study plan of non-teaching degrees. The credits would have to be taken from other courses to which they are currently allocated. As the deans of non-teaching degrees are reluctant to change their current distribution of credits, the supervisor suggests ways to increase their awareness:

The work has to be done over there [in non-teaching degrees]. They need to understand that in a globalised world, speaking English and having technological competences will strengthen students’ profile… If it’s not clear for them, [our job] is difficult.

Figure 5

Overall Participants’ Suggestions to Improve the Compulsory English Courses

Discussion and Conclusion

In conclusion, the Compulsory English Courses are failing to meet stakeholders’ needs (figure 5). Both current and former students request an approach towards learning English that is beneficial to their career prospects, that is, ESP. Teachers are dissatisfied with facilities and have requested increased resources, as well as a greater sense of teamwork within the English Teaching Department. Finally, the supervisor is dealing with the university credit system and the lack of awareness of the importance of English among deans of faculties, especially those of non-teaching degrees.

Based on the results of this study, the following recommendations for future research are proposed. First, there should be further exploratory studies on the implementation of ESP in Colombian universities. These may contribute to understanding how to transition to ESP from English courses in which EGP has long been used. Second, considering criticism of the textbook, more studies would be useful on the alternatives available for teachers, thereby avoiding a dependency on the textbook. These may include providing instruction for teachers on how to design their own materials in a more efficient way, as well as using authentic resources. Lastly, in the specific case of USCO, a study on the differences between the proficiency level of students from teaching degrees and non-teaching degrees may be beneficial. This may indicate whether the fact of granting credits, as well as the difference in the number of hours of teaching, plays a role in achieving the English proficiency level set out by Colombian national foreign language policies.

References

Alonso, J., Estrada, D., & Mueces, B. (2018). Nivel de inglés de los programas de Administración de Empresas en Colombia: la meta está lejos. Estudios Gerenciales, 34(149), 445-456. https://doi.org/10.18046/j.estger.2018.149.2881

Arias-Contreras, C., & Moore, P. (2022). The role of English language in the field of agriculture: A needs analysis. English for Specific Purposes, 65, 95-106. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.esp.2021.09.002

Benavides, J. (2021). Level of English in Colombian Higher Education: A Decade of Stagnation. Profile: Issues in Teachers’ Professional Development, 23(1), 57-73. https://doi.org/10.15446/profile.v23n1.83135

Berwick, R. (1989). Needs Assessment in Language Programming: from Theory to Practice. In R. Johnson (Ed.), The Second Language Curriculum (pp. 48-62). Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/cbo9781139524520.006

Brindley, G. (1989). The role of needs analysis in adult ESL programme design. In R. Johnson (Ed.), The Second Language Curriculum (pp. 63-78). Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/cbo9781139524520.007

Brinkmann, S., & Kvale, S. (2018). Doing Interviews (2nd ed.) SAGE. https://doi.org/10.4135/9781529716665

Brown, J. (2009). Foreign and Second Language Needs Analysis. In M. Long & C. Doughty (Eds.), The Handbook of Language Teaching (pp. 267-293). Blackwell Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781444315783.ch16

Cárdenas, N. (2018). Perspectivas para un estudio sobre bilingüismo en universidades regionales colombianas. Revista Historia de la Educación Latinoamericana, 20(31). https://doi.org/10.19053/01227238.8566

Castillo, R., & Pineda-Puerta, A. (2016). The Illusion of the Foreign Language Standard in a Colombian University. Latin American Journal of Content and Language Integrated Learning, 9(2), 426-450. https://doi.org/10.5294/laclil.2016.9.2.8/426-450

Consejo Superior de la Universidad Surcolombiana. (2009, december 18). Acuerdo 065.

Creswell, J., & Poth, C. (2018). Qualitative Inquiry Research Design Choosing Among Five Approaches (4th ed.). SAGE.

Dudley-Evans, T. (2001). English for Specific Purposes. In R. Carter & D. Nunan (Eds.), The Cambridge Guide to Teaching English to Speakers of Other Languages (pp. 131-136). Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/cbo9780511667206

Dudley-Evans, T., & St. John, M. (1998). Development in English for Specific Purposes a Multi-disciplinary Approach. Cambridge University Press.

Garcia-Ponce, E. (2020). Needs Analysis to Enhance English Language Proficiency at a Mexican University. Profile: Issues in Teachers’ Professional Development, 22(2), 145-162. https://doi.org/10.15446/profile.v22n2.82247

Garcia-Ponce, E., Mora-Pablo, I., & Lengeling, M. (2021). Needs Analysis in Higher Education: A Case Study for English Language Achievement. I-Manager’s Journal on English Language Teaching, 11(2), 1-11. https://doi.org/10.26634/jelt.11.2.17476

Gómez, J. (2017). Creencias sobre el aprendizaje de una lengua extranjera en el contexto universitario. Íkala, Revista de Lenguaje y Cultura, 22(2), 203-219. https://doi.org/10.17533/udea.ikala.v22n02a03

Harper, J., & Widodo, H. (2018). On the Design of a Global Law English Course for University Freshmen: a Blending of EGP and ESP. European Journal of Applied Linguistics and TEFL, 7(1), 171-188. https://search-proquest-com.ezproxy.is.ed.ac.uk/docview/2343015308?pq-origsite=primo&accountid=10673

Hutchinson, T., & Waters, A. (1987). English for Specific Purposes: A Learning-Centred Approach. Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/cbo9780511733031

Icfes Saber Pro. (2021). Reporte de Resultados por Aplicación Examen Saber Pro Instituciones de Educación Superior 2021. https://www.icfes.gov.co/documents/39286/1258809/Base+de+datos+de+resultados+agregados+de+saber+pro+2021+V2.xlsx

Jaime, M., & Coronado, C. (2018). Impacto de los materiales del programa de inglés en una universidad pública de Colombia. Cuadernos de Lingüística Hispánica, (32), 175-193. https://doaj.org/article/3d18bd279fb1416a8785ba9892f093bd

Li, Y., & Heron, M. (2021). English for General Academic Purposes or English for Specific Purposes? Language Learning Needs of Medical Students at a Chinese University. Theory and Practice in Language Studies, 11(6), 621-631. https://doi.org/10.17507/tpls.1106.05

Macalister, J., & Nation, I. (2020). Language Curriculum Design (2nd ed). Taylor & Francis Group.

Ministry of National Education. (2014). Colombia Very Well Programa Nacional de Inglés 2015-2025. https://www.academia.edu/32878359/PROGRAMA_NACIONAL_DE_INGLÉS_2015_2025

Miranda, N., & Valencia, S. (2019). Unsettling the ‘Challenge’: ELT Policy Ideology and the New Breach Amongst State-funded Schools in Colombia. Changing English, 26(3), 282-294. https://doi.org/10.1080/1358684X.2019.1590144

Mosquera, C. (2022). Learning Needs of English and French Students from a Modern Languages Program at a Colombian University. HOW, 29(1), 9-36. https://doi.org/10.19183/how.29.1.595

Nuñez, A. (2018). The English Textbook. Tensions from an Intercultural Perspective. GiST Education and Learning Research Journal, (17), 230-259. https://doi.org/10.26817/16925777.402

Patton, M. (2015). Qualitative Research & Evaluative Methods (4th ed.). SAGE.

Pennington, M., & Richards, J. (2016). Teacher Identity in Language Teaching: Integrating Personal, Contextual, and Professional Factors. RELC Journal, 47(1), 5-23. https://doi.org/10.1177/0033688216631219

Poedjiastutie, D., & Oliver, R. (2017). English Learning Needs of ESP Learners: Exploring Stakeholder Perceptions at an Indonesian University. TELFIN Journal, 28(1), 1-21. https://doi.org/10.15639/teflinjournal.v28i1/1-21

Pradana, A., Yunita, W., & Diani, I. (2022). What do nursing students need in learning English? Journal of Applied Linguistics and Literature, 7(2), 321-344. https://doi.org/10.33369/joall.v7i2.14819

Richards, J. (2017). Curriculum Development in Language Teaching (2nd ed.). Cambridge University Press.

Rossett, A. (1982). A typology for generating needs assessments. Journal of Instructional Development, 6(1), 28-33. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02905113

Said, M., & Herlina, L. (2022). Need Analysis in Learning English for Law Students. Advances in Social Sciences Research Journal, 9(5), 420-428. https://doi.org/10.14738/assrj.95.12438

Salamanca, S. (2020). Subjective Needs Analysis: A Vital Resource to Assess Language Teaching. Mextesol Journal, 44(3). http://www.mextesol.net/journal/index.php?page=journal&id_article=21396

Sánchez, A., Obando, G., & Ibarra, D. (2017). Learners’ Perceptions and Undergraduate Foreign Language Courses at a Colombian Public University. HOW, 24(1), 63-82. https://doi.org/10.19183/how.24.1.310

Schutz, N., & Derwing, B. (1981). The Problem of Needs Assessment in English for Specific Purposes: Some Theoretical and Practical Orientations. In R. Mackay & J. Parmer (Eds.), Languages for Specific Purposes: Program Design and Evaluation (pp. 29-49). Newbury House.

Schwandt, T., & Gates, E. (2018). Case Study Methodology. In N. Denzin & Y. Lincoln (Eds.), The SAGE Handbook of Qualitative Research (5th ed., pp. 341-358). SAGE.

Thomas, G. (2021). How to do your Case Study (3rd ed.). SAGE Publications Ltd.

Trujeque-Moreno, E., Romero-Fernández, A., Esparragoza-Barragán, A., & Villa-Jaimes, C. J. (2021). Needs Analysis in the English for Specific Purposes (ESP) Approach: The Case of the Benemérita Universidad Autónoma de Puebla. Mextesol Journal, 45(2). https://www.mextesol.net/journal/index.php?page=journal&id_article=23562

Viana, V., Bocorny, A., & Sarmento, S. (2018). Teaching English for Specific Purposes. Tesol Press.

West, R. (1994). Needs Analysis in Language Teaching. Language Teaching, 27(1), 1-19. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0261444800007527

Zúñiga, G., Insuasty, E., Macías, D., Zambrano, L., & Guzmán, N. (2009). Análisis de las Prácticas Pedagógicas de los Docentes de Inglés del Programa Interlingua de la Universidad Surcolombiana. Entornos, 1(22), 11-20.