Tattoos and Body Modification: Culture, Therapy, and History

Abstract

Tattooing has been transforming its meaning over time, it is a practice related to fashion, the dominance of aesthetics over the body, beliefs, forms of expression and identity, a practice that has become commonplace in contemporary societies. The article is divided into two segments. The first summarizes a detailed review of 152 publications exploring various aspects of tattooing derived from a systematic review of the scientific production surrounding tattoos and how they have been conceived over time. The second includes an analysis of these articles based on their theoretical and conceptual contributions, expanding the literature on the study of tattooing (in categories such as: anthropological, gender perspectives, work environment considerations, medical factors and body modification practices). This research revealed a broad spectrum of conceptual and epistemological perspectives that have influenced the practice of skin inscription. It also highlights the important role that tattoos play in the practice of skin inscription.

Keywords: body, tattoo, body modification, contemporary subject, bio-art

Investigadora externa – Grupo de investigación GIFSE, Tunja (Boyacá), Colombia

cardenakaren505@gmail.com

2. Secretaria de educación de Casanare, Tauramena (Casanare), Colombia

Recibido: 29/Mayo/2024

Revisado: 13/Septiembre/2024

Aprobado: 19/Noviembre/2024

Publicado: 13/Diciembre/2024

Para citar este artículo: Cárdenas , K. A., & Torres , A. M. (2024). Tattoos and Body Modification: Culture, Therapy, and History. Praxis & Saber, 15(43), 1–21.

Karen Andrea Cárdenas 1

Aura Marcela Torres Torres

Tatuajes y Modificación Corporal: Cultura, Terapia e Historia

Resumen

El tatuaje ha ido transformando su significado a lo largo del tiempo, es una práctica relacionada con la moda, el dominio de la estética sobre el cuerpo, las creencias, las formas de expresión y la identidad, una práctica que se ha convertido en habitual en las sociedades contemporáneas. El artículo se divide en dos segmentos. El primero resume una revisión detallada de 152 publicaciones que exploran diversos aspectos del tatuaje derivados de una revisión sistemática de la producción científica en torno a los tatuajes y cómo han sido concebidos a lo largo del tiempo. La segunda incluye un análisis de estos artículos a partir de sus aportaciones teóricas y conceptuales, ampliando la literatura sobre el estudio del tatuaje (en categorías como: antropológica, perspectivas de género, consideraciones sobre el entorno laboral, factores médicos y prácticas de modificación corporal). Esta investigación reveló un amplio espectro de perspectivas conceptuales y epistemológicas que han influido en la práctica de la inscripción en la piel. También pone de relieve el importante papel que desempeñan los tatuajes en la práctica de la inscripción en la piel.

Palabras clave:cuerpo, tatuaje, modificación corporal, sujeto contemporáneo, bioarte

Tatuagens e Modificações Corporais: Cultura, Terapia e História

Resumo

A tatuagem vem transformando seu significado ao longo do tempo, é uma prática relacionada à moda, ao domínio da estética sobre o corpo, às crenças, às formas de expressão e à identidade, uma prática que se tornou comum nas sociedades contemporâneas. O artigo está dividido em dois segmentos. O primeiro resume uma revisão detalhada de 152 publicações que exploram vários aspectos da tatuagem, derivada de uma revisão sistemática da produção científica sobre tatuagens e como elas foram concebidas ao longo do tempo. A segunda inclui uma análise desses artigos em termos de suas contribuições teóricas e conceituais, expandindo a literatura sobre o estudo da tatuagem (em categorias como: antropologia, perspectivas de gênero, considerações sobre o ambiente de trabalho, fatores médicos e práticas de modificação corporal). Essa pesquisa revelou um amplo espectro de perspectivas conceituais e epistemológicas que influenciaram a prática da inscrição na pele. Ela também destaca a importante função que as tatuagens desempenham na prática da inscrição na pele.

Palavras-chave:corpo, tatuagem, modificação corporal, sujeito contemporâneo, bioarte

Introduction

Tattooing is a human practice that has transcended different cultures and meanings from the trivial and/or ancestral to the aesthetic due to the increasing expansion of diversity and techniques that have driven it to become a popular practice in today’s society. It went from being a ritual with purposes associated with hegemonies, marks, and ancestry, to being contemplated as an adornment or decoration of the body, a work around the skin full of semiotic connotations, and alternative ways of life.

Tattooing allows the body to be modeled according to the desires of the subject. Tattooing is a form of self-expression that allows individuals to modify their bodies based on their personal preferences. It is a part of how humans construct and communicate their identities. Tattoos are a form of self-government, subjectivization, and dominion over the body that creates an artificial sphere and defines man as a singular subject against a traditional culture (López-Naranjo et al., 2023). Therefore, tattoos are considered an object of study relevant to understanding the transculturation behind the tattoo itself, not only in language but also in culture and society.

Tattooing is a form of letting oneself be operated on the individual body, where the body functions as an expression of personal and societal values. According to Foucault (2002), it would lead the power to a general system of domination exercised by one element or group over another, and whose effects, thanks to successive derivations, would cross the entire social body. Likewise, the body undergoes cultural, social, and political transformations, being aware of its mutation from the incomplete feeling of the subject, which leads to a symbolic exploration of itself through this contemporary artistic practice.

This article reviews the production of tattooing through a conceptual-theoretical search in the Scopus database, from which 305 documents were collected. Of the total number of files retrieved, 152 were analyzed and then classified, thematized, and analyzed according to their relationship with these two variables: 1) general characteristics of the articles, and 2) specific variables related to the body-tattoo relationship.

Methodology

Data collection.

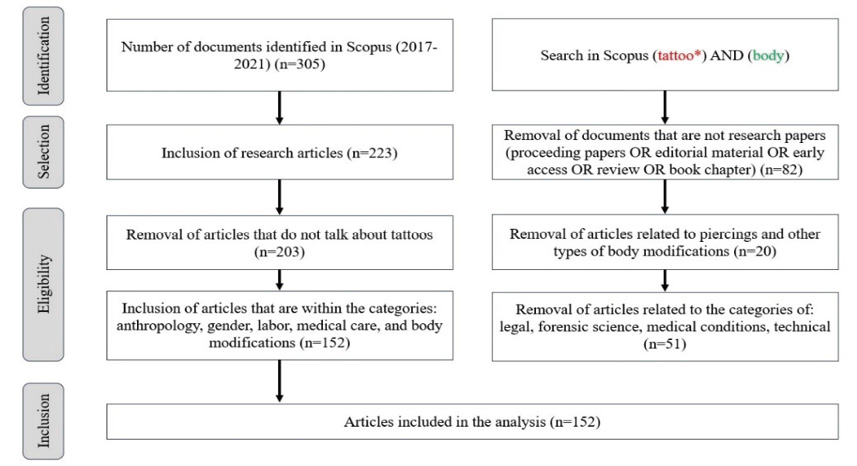

To gain insights into bodily modifications, an exhaustive review of scientific literature on tattoos and their changing conceptualizations was conducted. Other authors have used this type of review to create narrative constructions of the emergence of tattooing and its evolution and, in those cases where the medical aspect predominates, to analyze skin care techniques when tattooing or when dermatological complications occur. A search and selection of articles was performed based on Moher et al.’s (2009) model (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Flowchart of the systematic literature review selection process

Source: Based on Moher et al. (2009)

For the identification of scientific articles addressing body issues and their relationship to tattooing, a search for peer-reviewed papers was designed. This search included different methodologies and research disciplines. The identification process involved the selection of a variety of terms that were included in the search equation. The search was conducted in Scopus between 2017 and 2021, yielding a total of 305 documents.

Regarding the selection, in this step, only research articles were considered. Therefore, documents such as proceedings, editorial materials, reviews, book chapters, and other editorial materials were excluded (n=223).

Eligibility was done through two selections. In the first selection, documents that did not specifically talk about tattoos were eliminated, i.e., articles whose main topic was piercings and other types of body modifications (n= 203). In the second selection, the articles were thoroughly read and classified into nine categories: 1. Anthropologic, 2. Gender, 3. Work environment, 4. Medical care, 5. Body modifications, 6. Legal, 7. Forensic Science, 8. Medical conditions, 9. Technical. Of these nine categories, four were discarded (legal, forensic science, medical conditions, and technical) because they were not relevant to the investigation. Finally, in the inclusion section, 152 articles related to the remaining five categories were selected.

Data analysis.

Variables associated with: 1) general characteristics of the articles, and 2) specific variables related to body-tattooing, were coded using the content analysis technique, which allows the identification of main themes, concepts, or variables through a rigorous examination of the text (Riffe et al., 2005). A total of nine categories of analysis were systematically coded in each of the 152 articles (Appendix 1).

First, a descriptive analysis of the variables of temporal evolution (concentration and dispersion per country) was conducted. This analysis considered the place of publication of the article as opposed to the author’s origin (The graph was created using Visme software). Concentration and dispersion by journal were also analyzed. For this purpose, a list was made of the places where the journals containing the articles used for this research were published. This list was then used to search for the publisher. Finally, a keyword co-occurrence analysis by category was performed using VOS viewer software. Subsequently, the articles were systematically classified using analysis sheets. These sheets served to categorize the articles according to the relationships they addressed between body and tattoo.

Results

The results of the analyses, in relation to the general features of the articles, are presented below.

Time evolution

Within the analyzed articles, 152 documents were found in the period of 2017-2021. Figure 2 shows that publications were constant during these five years.

Figure 1. Time evolution - No. of articles per year

The growing interest in the study of tattooing, as demonstrated by the review of articles, is derived from the boom in the practice of tattooing not only as a merely ancestral, symbolic, and/or cultural exercise but also because of the commercial and capital interest that this practice generates. More and more people are taking up tattooing, establishing the practice as an increasingly sought-after profession. Therefore, tattooing has become an object of discussion that has crossed borders and stereotypes socially assigned to people who modify their bodies, reaching not only artistic communities but also scientific ones.

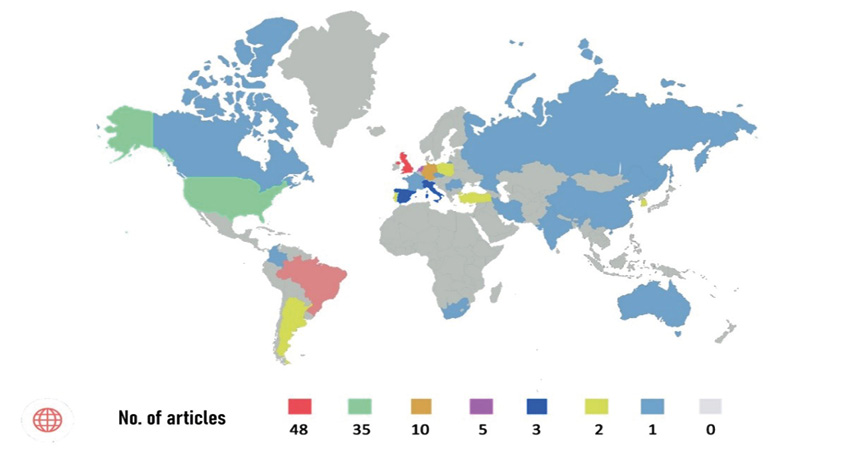

Concentration and dispersion per country. In terms of concentration and dispersion per country, publications were found in 27 countries. The countries with the highest concentration, that is, with the highest number of articles published on tattooing and its relationship to the body, are in Europe. The United Kingdom was the country with the highest number of articles, with a total of 48 (36.1 %), followed by Germany with 10 articles (7.5 %). The United States also presented a high concentration of publications, with a total of 35 articles (26.3%). Regarding Spanish-speaking countries, only 4% of the articles analyzed were published there.

Figure 2. Concentration per country

Source: Own elaboration

The dispersion of production per country for this research was high since we found that 19 countries had 2 or fewer publications. It is important to note that the analysis of concentration per country, in this case, was based on the place where the article was published and not on the place of origin of the authors.

Concentration and dispersion per journal. The data collected in this research allowed us to identify the concentration and dispersion of the journals in which the analyzed articles were published. The analysis was limited to those journals that had published at least two articles. The reason behind this is that the journals with only one publication do not provide any compelling evidence of a high concentration. From the total of 152 articles, only 127 journals were identified. Thus, suggesting a diverse range of publications rather than a high concentration in a single number of journals.

According to Appendix 2, the journal “Deviant Behavior” of the University of Louisiana published the highest number of articles analyzed, with 4 articles (2.6%). They are followed by the European Journal of Applied Physiology, Journal of Archaeological Science, and Asia Pacific Journal of Anthropology, each with 3 articles (2.0%). In addition, 11 journals were identified that published 2 articles each (1.3%). The results also showed a high dispersion of 88%.

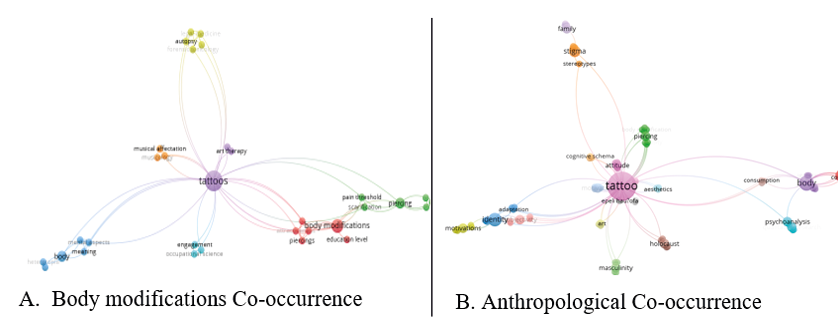

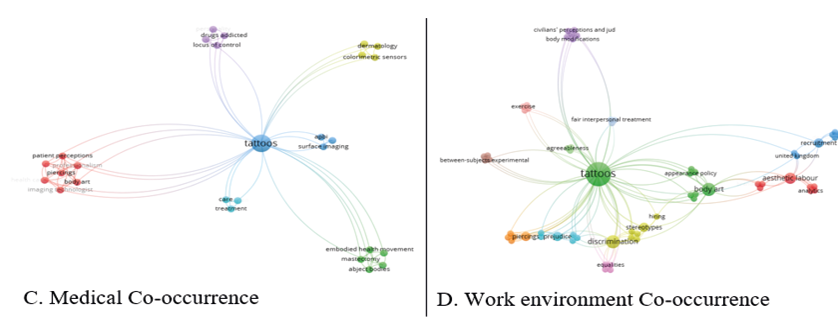

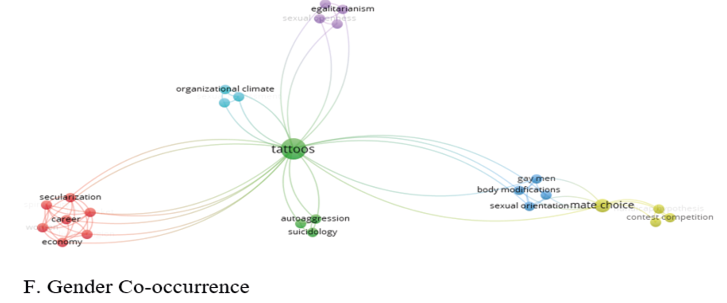

Keyword co-occurrence network. From the analysis of the keywords contained in the articles, we can establish a network of co-occurrences for each of the analyzed categories in Figure 3, created from the words that appear a minimum of two times in the corpus documents. The keyword tattoo is presented as the prominent center of the network. However, each of the networks show particularities according to the category. For example, the network related to the body modification category is associated with words such as body, piercing, and autopsy, whereas for the network of the anthropological category, words such as identity, motivation, and family are the ones that stand out.

Figure 3. Co-occurrence of keywords

Source:Own elaboration

Data Analysis

The following is the content analysis derived from the categories mentioned in the documentary search and tracking in the study of tattooing.

Anthropological

This category recognizes “anthropologies of the body” as that which views the skin as a canvas on which meanings, symbols, stories, and experiences are inscribed, so that the body becomes a biological-cultural-technical artifact (Smith et al., 2021). The anthropological study primarily focuses on analyzing and reflecting on the symbolism of tattoos, their interpretation, social perceptions, cultural experiences, life narratives and their interpretations. It also explores the relationship between tattoos and their biological counterpart.

The cultural perception of tattoos is derived from the anthropological. Some authors such as Zestcott et al., (2017), Guerzoni (2018), Weiler and Jacobsen (2021), Tranter & Grant (2018), Broussard & Harton (2018), Timming & Perrett (2017), and Lane (2017) state that people with tattoos are attributed with prejudices and stereotypes related to gender, aesthetics, sexual orientation, race, beliefs, social class, and values that alter the subject’s identity. For Perez-Floriano (2018), Hong and Lee (2017), and Naude et al. (2019), tattoos generate different qualifiers that are related to the aesthetic and conceptual look. Therefore, not only the tattoo is valued, but also the person who carries it. Therefore, creating objective and subjective descriptions. Likewise, Sizer (2020) mentions that subjects live the tattoo experience in different ways, from the construction of subjectivity, cultural production, artistic practices, belonging (Patterson, 2018), and fashion (Julien, 2020). In the words of Jaworska et al. (2018):

“The practice of tattooing has come a long way from primitive cultures, where it had a ritual and magical significance, to criminal subcultures, where it marked group affiliation, to modern times, when it became an important element of fashion” (p. 6).

That is, this practice has been part of collective identification and has been used as means for the appropriation of an identity (Davey & Zhao, 2019; Dougherty & Koch, 2019; Lammek, 2020).

This category also makes the body visible as an archive. For Strubel & Jones (2017), and Sparkes et al. (2021), the tattoo on the body functions as a record, a tangible and subjective archive composed of experiences, memories, and emotions linked to human relationships. In the same vein, tattooing is also tied to an individual’s wish to depict a certain aspect of their identity, their feelings, and their intention to connect with the concept of self-reaffirmation (Sims, 2018). For Klik (2020) and Steadman et al. (2019) subjects assign memorial values to body modifications, reliving memories through the skin, expressing narratives, commemorating loved ones (Bloch, 2022; Hill, 2020) and other forms of storytelling, including as a therapeutic function, or as a ritual to heal emotional wounds (Crompton et al., 2021), but which also have connotations of consumption centered on the body and the inscription of temporality on the skin (Kayiran et al., 2020).

A final subcategory is found in the ancestral, a look at early tattoo practices that embrace dimensions of the past. Authors such as St-Pierre, (2018), Gillreath-Brown et al. (2019), Jelinski (2018), Barabas (2019), Friedman et al. (2018), and Ragragio & Paluga (2019) present some primitive techniques for tattooing. This study explores the tattooed skins of our ancestors, revealing individual and collective aspects of their past lives. It connects cultural, historical, and biological elements of distant civilizations such as Egypt and Utah, providing a timeless view of their connection. Similarly, Hegarty (2017) and Iftekhar and Zhitny (2020) argue that tattooing, as an ancestral practice, has been transculturated into indigenous cultures and contemporary ethnic groups. Although still part of their rituals, it now has modern connotations (Bennett & Wilkins, 2020).

In conclusion, these three subcategories focus on tattoos as a historical cultural practice. This practice has roots in the symbolism and rituals of ancient civilizations and is now associated with personal identity and social, cultural, and individual affiliations in modern times. Therefore, it forms a research field centered on the body as an anthropological/cultural artifact. This artifact serves as a repository of semantic, artistic, and ancestral elements that demonstrate how tattoos have been used to assert control over the body. Moreover, it highlights how tattoos have challenged conventional ways of interacting with the world throughout history.

Gender

Tattooing is also related to the category of gender, which alludes to or relates to the belief or stereotype that tattoos can be assigned to men, or to women, in order to fulfill a function and/or role according to their sex. Tattoo culture generates distinctive conditions between the two gender roles. Historically, tattoos were predominantly associated with males (Witkos & Hartman-Petrycka, 2020). However, the increase of women sporting tattoos can now be seen as a dismantling of traditional gender norms, particularly when viewed from a stereotypical point of view. This category revealed two subcategories related to gender, demonstrating that tattoos not only modify social perceptions but also assign specific attributes to opposite sexes.

On one hand, there is the subcategory we call “Tattoo as gender resistance” which provides conceptual notions about how both sexes grant a distinctive function to tattooing. Choudhury and Bhattacharyya (2020), along with Rahbari et al. (2019), examine how women use tattoos as a form of resistance against the suppression of their bodies. A prominent example is the political and sociocultural situation in Iran, where women have no control over their bodies due to the biopolitical state conditions. Maxwell et al. (2020) conducted a similar study by exploring how tattooing can be an alternative therapeutic medium for women who have experienced sexual violence trauma. In this context, women use tattoos as a way of “reclaiming and asserting control over their bodies.” The tattoo defies the “sanctity” that was politically imposed by the state and becomes a symbol of their fight and dignity. It can also be a mean to achieve body perfection in cases of body non-acceptance and disorders related to low self-esteem (Geller et al., 2020; Kertzman et al., 2019; Merinov & Vasilyeva, 2020). In addition, tattooing is seen as a symbol of femininity and an expression of personal purpose (Dann & Callaghan, 2019)

In contrast to women, tattooed men are perceived as stronger, dominant, masculine, and attractive, according to studies by Galbarczyk et al. (2020), Galbarczyk and Ziomkiewicz (2017), and Molloy and Wagstaff, (2021). However, they are also associated with violent and ‘deviant’ behaviors. Miller-Idriss (2017) discusses how tattooing contributes to the construction of masculinity in young men, in terms of value formation and experiences of risk. Conversely, the sexualization of tattooing in women has led to research on the bias and marginalization faced by tattooed women across different settings. Lee (2017) and Tews and Stafford (2019) explore the sexual attention that visible tattoos generate in women, especially in work contexts. Similarly, the study made by Skoda et al. (2020) shows how tattooed women receive more sexual attention and are perceived as more “accessible” than non-tattooed women, according to gender stereotypes. Visibly tattooed women can be perceived in two ways: first, as stronger and more confident women, or second, as sexually open and promiscuous, among other negative labels (Orr, 2017).

This final category addresses sociocultural perceptions of tattooing from a gender perspective. Tattooing is presented as a multifocal discourse that can alter the image and notion of individuals based on beliefs and stereotypes. It was found that, in both sexes, tattoos can be perceived as signs of health, attractiveness, and self-confidence, and as symbols of strength and identity. However, they are also associated with violence, promiscuity, low self-esteem, and harmful behaviors.

Medical Care

Articles that respond to medical applications and implications of the practice of tattooing both in living bodies and postmortem have been grouped in this research category. Throughout the analysis of the medical care category, three subcategories were found: psychoimmunological, socioimmunological, and biological.

Regarding the subcategory of socioimmunological, authors such as Birngruber et al. (2020) and Levy (2020) recognize that tattoos have positioned themselves as important tools to be used in legal processes. Tattooing is presented as a way for subjects to express their desire not to be resuscitated in case of an emergency. However, there is an ethical discussion about how to proceed when encountering a tattoo that expresses the desire not to be resuscitated, and the question is: How much validity does a symbol engraved in the skin have? These types of non-resuscitation orders continue to be a medical and legal problem since there is a shortage of resources on the subject. However, tattoos can serve as a solution by providing visible information to emergency service professionals who need to make a quick decision about the patient’s resuscitation. In this context, tattoos can provide a clear, immediate visual cue, which is crucial given the limited amount of time available during these situations (Levy, 2020).

Birngruber et al. (2020) conducted research in Jalisco, Mexico, to determine the potential role of tattoos in identifying the bodies of unidentified deceased persons. Postmortem data of 2045 bodies from the Jalisco Institute of Forensic Sciences in Guadalajara was evaluated. His study showed that tattoos have a functionality beyond artistic expression or aesthetic taste (Ondruschka et al., 2017), even in postmortem tasks such as identifying bodies.

In the psychoimmunological category, authors such as Komiya and Iwahira (2017), Osborn and Cohen (2018), and Reid-de Jong and Bruce (2020) identify the art of tattooing as a tool that favors self-expression, healing, and transformation of people who have gone through diseases that have left phenotypic imprints on their bodies, such as a mastectomy, ocular melanoma, or vitiligo.

Tattoos have played a crucial role in the treatment of breast cancer, being used in both cosmetic reconstruction and radiation treatments. Considered a heteronormative body ideal in society, the absence of mammary glands can have significant emotional consequences for women who have had to undergo mastectomy. These women may feel less feminine, less attractive, and experience decreased sexuality (Komiya & Iwahira, 2017). According to Reid-de Jong & Bruce (2020): “Post-mastectomy tattooed bodies enrich the discourse on what constitutes beauty, femininity, and sexuality while offering these women the agency to reclaim their bodies and refine their self-concepts” (p. 695). In breast cancer, tattoos have been used in patients undergoing accelerated partial breast irradiation, in order to aid in alignment and verification of daily settings (Jimenez et al., 2019; Osborn & Cohen, 2018).

Aesthetic tattoos have been used in the treatment of patients with vitiligo to help them feel better about their bodies and meet beauty standards (Ju et al., 2020; Kluger, 2017). In addition, corneal tattooing with Rotring drawing ink has been shown to be effective in the cosmetic improvement of disfigured blind eyes, achieving favorable results and high patient satisfaction. This technique is an alternative to more sophisticated cosmetic reconstructive surgeries (Rodriguez-Avila et al., 2020; Santos da Cruz et al., 2017) and is considered an affordable surgical procedure to improve cosmetic appearance in eyes with disfiguring corneal opacities (Alsmman et al., 2018).

Regarding the biological subcategory, authors such as Yetisen et al. (2019) identified other uses of tattooing on the body as biosensors. Tattooing is a ubiquitous body modification that involves the injection of ink or coloring pigments into the dermis. Biosensors in the form of tattoos can be used to monitor metabolites in interstitial fluid. Here, minimally invasive, injectable dermal biosensors were developed to measure pH, glucose, and albumin concentrations. The sensors were multiplexed on a skin tissue sample, and quantitative readings were obtained using a smartphone camera.

Work environment

The analysis of the work environment category showed how tattoo body art can influence the labor market, affecting aspects such as selection during a job interview, salary perception, bosses’ perceptions of their employees, and the general work environment. Although it is recognized that visible body modification is an expression of sociocultural trends, as well as an individual’s personal experiences, values, expectations, and knowledge, attitudes toward such body modifications can influence hiring practices (Uzunogullari & Brown, 2021). In the analysis of the influence of tattoo body art, two main trends were identified: tattooing as a stereotype that carries stigmatization and tattooing as a common practice in modern society.

Regarding tattooing as a stigmatizing stereotype, authors such as Hauke-Forman et al (2021), Henle et al (2021), Tews & Stafford (2019), and Thielgen et al. (2020) acknowledge that tattooing is not an approved practice within traditional etiquette codes. For, tattooed people, as a loosely constituted social group, are apparently labeled as a disadvantaged community of individuals commonly associated with lower-class countercultural offenders (Brown et al., 2010). Additionally, tattooed individuals are considered to be more likely to engage in risky behaviors compared to their non-tattooed counterparts (Mortensen et al., 2019).

Preconceived religious and sociocultural ideas about people with visible tattoos create negative implications for hiring in the workplace, which could prevent organizations from recruiting and retaining talented employees. This implies that talented employees may experience bias in job interviews, which prevents them from obtaining employment (Adisa et al., 2021). According to Tews and Stafford (2019), employees with a higher number of visible tattoos tend to receive less favorable treatment, which is reflected in interpersonal relationships and perceived discrimination. Furthermore, these tattooed employees are commonly given reduced pay and judged as less competent in comparison to candidates who do not have visible tattoos (Henle et al., 2021). However, this job and wage discrimination is mainly affected by two factors: the type of profession and the age of the interviewers. Regarding the type of profession, discrimination is more evident in sectors such as health, beauty, retail, and customer service (French et al., 2019).

A study by Hauke-Forman et al (2021) found that police officers with tattoos and piercings are perceived as less trustworthy and competent. On the other hand, the age of the interviewers also plays an important role. According to a study by Tews et al (2020), interviewers from the millennial generation tend to view candidates with light tattoos more positively than older interviewers. Although there are numerous studies that recognize tattooing as a factor of discrimination and unequal treatment in the workplace, more research is still needed to probe further into the subject and include new categories of analysis (Thielgen et al., 2020).

In the work environment category, a trend has been identified that considers tattooing as a practice of the contemporary individual. Authors such as French et al (2019), Mironski and Rao (2019), Thompson (2020), and Timming (2017) argue that, at present, clothing and tattoos do not define an individual’s job competencies. Hence, there has been a notable change in societal views towards this form of body art, gradually altering stereotypes to acceptance (Mironski & Rao, 2019).

Tattooing is positioning itself as a common practice, as people’s appearance is becoming less and less important when assessing employee competence, professionalism, caring, approachability, trustworthiness, or reliability (Cohen et al., 2018). This has allowed the body art of tattooing to be used strategically to positively convey the brand of organizations, especially those targeting a younger, edgier audience (Timming, 2017). In addition, it is consolidating new ways of perceiving individuals. For example, Generation X and Millennial teachers with subcultural affiliations and alternative appearances, including visible tattoos, are changing the image of the modern teacher (Thompson, 2020). However, this freedom of dress and body art generally applies to white heterosexual men, while those with increasingly marginalized identities still feel pressured to follow the standard of a more conservative wardrobe (Thompson, 2020).

There are two main trends in this category. The first is a traditional hegemonic trend, based on religious conceptions and socially conservative dress codes. This trend reflects the problems of stigmatization and job discrimination, where people with visible tattoos are considered less competent and reliable, receive lower wages, and are often rejected because of their physical appearance. The second trend is the result of the normalization and acceptance of tattooing as a contemporary artistic practice. This trend is directly related to the generational change in the workplace, as new workers belong to Generation X and Millennials. These generations’ view of the body is different from that of older people, which has led to greater acceptance of tattoos in the workplace.

Body modifications

In the analysis of tattoos as a practice of the contemporary subject, tattooing was related to the concept of body modifications, which are understood as invasive interventions on the human body, especially interventions on the human skin that result in (semi-) permanent changes (Liebermann, 2021). Currently, tattoos are understood as fashion adornments, body art, and a mechanism to express pain that integrates a social and cultural reality (Aldaz et al., 2021) that possesses a preference over less dangerous options (Lynn et al., 2019). Therefore, two subcategories were outlined: tattooing as a fashion artifact and as a canvas for expression.

Tattoos have positioned themselves as a fashionable artifact, since people do not always get them with a specific meaning, but rather as a response to an impulse or to enhance their concept of beauty (Aldaz et al., 2021; Henley & Porath, 2021). For example, tattoos have become a recurring YouTube narrative with a large number of viewers (Frankel et al., 2021). According to studies by Tomaz and Neves (2019) in schools, tattoo fashion is spreading rapidly as a trend among female minors.

In the subcategory of tattooing as a canvas of expression, the body is perceived not as a biological construct but as an artistic and expressive canvas. On this canvas, narratives detailing experiences, emotions, intimate relationships, challenges, and significant connections are engraved permanently into the skin. Consequently, the tattoo is not a part of the subject’s body, but a synthesis of it (Keagy, 2020). Thus, tattoos serve as an expression of personalities and are specifically prevalent among individuals with a need to communicate their individuality (Kalanj-Mizzi et al., 2019) or a sense of group affiliation, as observed in communities such as heroin addicts who often incorporate religious or Christian symbols into their tattoos (Katsos et al., 2018).

Conclusions

Academic production in terms of the relationship between the body and tattoos has remained stable over the last five years, demonstrating the validity and importance of research development in the area. In terms of scientific production by country, there is evidence of low production in Latin American countries, which indicates that the theoretical reviews carried out in the area require a review of production in repositories and databases that focus on these territories, such as: La Red de Revistas Científicas de América Latina y el Caribe, España y Portugal, Redalyc, and Scielo.

The results obtained through the analyzed categories define tattoos as an identity symbol composed of a set of experiences, feelings, and actions that individuals capture in their bodies. These symbols fulfill their function by materializing a memory, becoming an immortalized mark of lived events, and enhancing the relationship of the individual with his own culture and social environment. This phenomenon is analyzed from artistic and cultural components that convey a part of the individual’s intimacy, such as a personal diary that arises from the practice of governing one’s own body. Similarly, these aspects can also be approached from a visual and social hierarchy.

Tattooing, as a form of body art and a growing industry, experiences a “transculturation” within the social context. This process involves technical advances and theoretical and symbolic reformulations in the processes of body resignification and mastery over the body. Tattoos allow not only to intervene on the skin but also on the rituality and the various functions that this symbolic activity has on individuals, beyond the recreation of desired bodies. Tattooed bodies allow tattooing to be a tool for social construction, generating cultural clashes and allowing the perception of the body and tattooed skin to be rethought. These studies help to reformulate social, cultural, and political discourses on the body, with transformations arising from the artistic, medical, and cultural fields. Transculturation is driven by the recognition of otherness, understood from the different, the exotic, the strange, and, for many, the “abnormal.” This recognition has contributed to the reformulation of body standards, at least in 21st-century Western societies.

Final Statements

Authors’ contribution. Marcela Torres: Elaboration of the documentary corpus, search, methodological design and bibliometric analysis. bibliometric analysis.

Karen Cárdenas: Elaboration of documentary corpus, theoretical analysis, methodological design, written production.

Conflicts of interest. No conflicts of interest to be declared.

Funding. This article is derived from the research project “Anthropotechnique and exercise in the work of Peter Sloterdijk: implications for philosophy of education and contemporary educational practices. educational practices”, which had financial support from the calls for proposals of MINCIENCIAS.

Ethical implications. The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest that could have an impact on the that may have repercussions on the content of this article.

References

Adisa, T., Adekoya, O. and Sani, K. (2021). ‘Stigma hurts: Exploring employer and employee perceptions of tattoos and body piercings in Nigeria’, Career Development International, 26(2), pp. 217-237. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1108/CDI-09-2020-0239.

Aldaz, L., Fuentes, A., Vailati, P. and Arko, B. (2021). ‘Perceptions about Tattoo as a cultural expression in AMBA: Interdisciplinaria, 38(1), pp. 235-243. Available at: https://doi.org/10.16888/interd.2021.38.1.15.

Alsmman, A., Mostafa, E., Mounir, A., Farouk, M., Elghobaier, M. and Radwan, G. (2018). ‘Outcomes of Corneal Tattooing by Rotring Painting Ink in Disfiguring Corneal Opacities,’ Journal of Ophthalmology, 2018. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1155/2018/5971290.

Barabas, T. (2019). ‘In(k)scribed Identities: A Sociological Analysis of Catholic Croat Tattoos,’ AM Journal of Art and Media Studies, 18, pp. 33-50. Available at: https://doi.org/10.25038/am.v0i18.297.

Bennett, L. and Wilkins, K. (2020). ‘Viking tattoos of Instagram: Runes and contemporary identities,’ Convergence: The International Journal of Research into New Media Technologies, 26(5-6), pp. 1301-1314. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1177/1354856519872413.

Birngruber, C., Pena, E., Blanco, L. and Holz, F. (2020). ‘The use of tattoos to identify unknown bodies Experiences from Jalisco, Mexico,’ Rechtsmedizin, 30(4), pp. 219-224. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00194-020-00396-y.

Bloch, A. (2022). ‘How memory survives: Descendants of Auschwitz: survivors and the progenic tattoo,’ Thesis Eleven. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1177/07255136211042453.

Boudreau, J., Ferro, L. and Villamar, A. (2020). ‘Being urban: a spatial-temporal perspective on tattooing’, Disparidades-Revista de Antropología, 75(2). Available at: https://doi.org/10.3989/dra.2020.022

Broussard, K. and Harton, H. (2018). ‘Tattoo or taboo? Tattoo stigma and negative attitudes toward tattooed individuals’, Journal of Social Psychology, 158(5), pp. 521-540. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1080/00224545.2017.1373622.

Brown, L., Mitchell, G., Holden, J., Folkard, A., Wright, N., Beharry-Borg, N., Berry, G., Brierley, B., Chapman, P., Clarke, S. J., Cotton, L., Dobson, M., Dollar, E., Fletcher, M., Foster, J., Hanlon, A., Hildon, S., Hiley, P., Hillis, P. and Woulds, C. (2010). ‘Priority water research questions as determined by UK practitioners and policymakers’, Science of the Total Environment, 409(2), pp. 256-266. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2010.09.040.

Choudhury, A. and Bhattacharyya, A. (2020). ‘Resisting Sexual Colonization, Reclaiming Denied Spaces: A Reading of Tattooed with Taboos: An Anthology of Poetry by Three Women from Northeast India,’ Rupkatha Journal on Interdisciplinary Studies in Humanities, 12(5). Available at: https://doi.org/10.21659/rupkatha.v12n5.rioc1s13n4.

Cohen, M., Jeanmonod, D., Stankewicz, H., Habeeb, K., Berrios, M. and Jeanmonod, R. (2018). ‘An observational study of patients’ attitudes to tattoos and piercings on their physicians: The ART study,’ Emergency Medicine Journal, 35(9), pp. 538-543. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1136/emermed-2017-206887.

Crompton, L., Amrami, G., Tsur, N. and Solomon, Z. (2021). ‘Tattoos in the Wake of Trauma: Transforming Personal Stories of Suffering into Public Stories of Coping,’ Deviant Behavior, 42(10), pp. 1242-1255. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1080/01639625.2020.1738641.

Dann, C. and Callaghan, J. (2019). ‘Meaning-making in women’s tattooed bodies,’ Social and Personality Psychology Compass, 13(3). Available at: https://doi.org/10.1111/spc3.12438.

Davey, G. and Zhao, X. (2019). ‘Tattoos, Modernization, and the Nation-State: Dai Lue Bodies as Parchments for Symbolic Narratives of the Self and Chinese Society*,’ Asia Pacific Journal of Anthropology, 20(2), pp. 165-183. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1080/14442213.2019.1573848.

Dougherty, K. and Koch, J. (2019). ‘Religious tattoos at one Christian university,’ Visual Studies, 34(4), pp. 311-318. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1080/1472586X.2019.1687331.

Frankel, S., Cuevas, L., Lim, H. and Benjamin, S. (2021). ‘Exploring Tattooed Presentation on YouTube: A Case Study of Kat von D’, Fashion Theory: The Journal of Dress Body & Culture. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1080/1362704X.2021.1882769.

French, M., Mortensen, K. and Timming, A. (2019). ‘Are tattoos associated with employment and wage discrimination? Analyzing the relationships between body art and labor market outcomes’, Human Relations, 72(5), pp. 962-987. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1177/0018726718782597.

Friedman, R., Antoine, D., Talamo, S., Reimer, P., Taylor, J., Wills, B. and Mannino, M. (2018). ‘Natural mummies from Predynastic Egypt reveal the world’s earliest figural tattoos’, Journal of Archaeological Science, 92, pp. 116-125. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jas.2018.02.002.

Galbarczyk, A., Mijas, M., Marcinkowska, U., Koziaa, K., Apanasewicz, A. and Ziomkiewicz, A. (2020). ‘Association between sexual orientations of individuals and perceptions of tattooed men’, Psychology & Sexuality, 11(3), pp. 150-160. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1080/19419899.2019.1679867.

Galbarczyk, A. and Ziomkiewicz, A. (2017). ‘Tattooed men: Healthy bad boys and good-looking competitors,’ Personality and Individual Differences, 106, pp. 122-125. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2016.10.051.

Geller, S., Magen, E., Levy, S. and Handelzalts, J. (2020). ‘Inkskinned: Gender and Personality Aspects Affecting Heavy Tattooing-A Moderation Model’, Journal of Adult Development, 27(3), pp. 192-200. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10804-019-09342-z.

Gillreath-Brown, A., Deter-Wolf, A., Adams, K., Lynch-Holm, V., Fulgham, S., Tushingham, S., Lipe, W. and Matson, R. (2019). ‘Redefining the age of tattooing in western North America: A 2000-year-old artifact from Utah’, Journal of Archaeological Science-Reports, 24, pp. 1064-1075. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jasrep.2019.02.015.

Guerzoni, G. (2018). ‘Devotional tattoos in early modern Italy’, Espacio Tiempo y Forma Serie VII-Historia del Arte, 6, pp. 119-135. Available at: https://doi.org/10.5944/etfvii.6.2018.22922.

Hauke-Forman, N., Methner, N., and Bruckmueller, S. (2021). ‘Assertive, but Less Competent and Trustworthy? Perception of Police Officers with Tattoos and Piercings’, Journal of Police and Criminal Psychology, 36(3), pp. 523-536. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11896-021-09447-w.

Hegarty, B. (2017). ‘`No Nation of Experts’: Kustom Tattooing and the Middle-Class Body in Post-Authoritarian Indonesia’, Asia Pacific Journal of Anthropology, 18(2), pp. 135-148. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1080/14442213.2016.1269833.

Henle, C., Shore, T., Murphy, K., and Marshall, A. (2021). ‘Visible Tattoos as a Source of Employment Discrimination Among Female Applicants for a Supervisory Position’, Journal of Business and Psychology. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10869-021-09731-w.

Henley, D., and Porath, N. (2021). ‘Body Modification in East Asia: History and Debates’, Asian Studies Review, 45(2), pp. 198-216. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1080/10357823.2020.1849026.

Hill, K. (2020). ‘Tattoo Narratives: Insights into Multispecies Kinship and Griefwork’, Anthrozoos, 33(6), pp. 709-726. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1080/08927936.2020.1824652.

Hong, B. and Lee, H. (2017). ‘Self-esteem, propensity for sensation seeking, and risk behaviour among adults with tattoos and piercings’, Journal of Public Health Research, 6(3), pp. 158-163. Available at: https://doi.org/10.4081/jphr.2017.1107.

Iftekhar, N. and Zhitny, V. (2020). ‘Tattoo and body art: A cultural overview of scarification’, International Journal of Dermatology, 59(10), pp. 1273-1275. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1111/ijd.15131.

Jaworska, K., Fijalkowska, M., and Antoszewski, B. (2018). ‘Tattoos yesterday and today in the Polish population in the decade 2004-2014’, Health Psychology Report, 6(4), pp. 321-329. Available at: https://doi.org/10.5114/hpr.2019.77175.

Jelinski, J. (2018). ‘“If Only It Makes Them Pretty”: Tattooing in “Prompted” Inuit Drawings’, Etudes Inuit Studies, 42(1-2), pp. 211-241. Available at: https://doi.org/10.7202/1064502ar.

Jimenez, R., Batin, E., Giantsoudi, D., Hazeltine, W., Bertolino, K., Ho, A., MacDonald, S. M., Taghian, A. and Gierga, D. (2019). ‘Tattoo free setup for partial breast irradiation: A feasibility study’, Journal of Applied Clinical Medical Physics, 20(4), pp. 45-50. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1002/acm2.12557.

Ju, H., Eun, S., Lee, H., Lee, J., Kim, G. and Bae, J. (2020). ‘Micropigmentation for vitiligo on light to moderately colored skin: Updated evidence from a clinical and animal study’, Journal of Dermatology, 47(5), pp. 464-469. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1111/1346-8138.15282.

Julien, M. (2020). ‘Les Tendances corporelles et vestimentaires des annees 2010: Fondement et symbolique d’une beaute artificielle et … Authentique’, Contemporary French and Francophone Studies, 24(1), pp. 35-45. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1080/17409292.2020.1754696.

Kalanj-Mizzi, S., Snell, T., and Simmonds, J. (2019). ‘Motivations for multiple tattoo acquisition: An interpretative phenomenological analysis’, Advances in Mental Health, 17(2), pp. 196-213. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1080/18387357.2018.1537127.

Katsos, K., Moraitis, K., Papadodima, S., and Spiliopoulou, C. (2018). ‘Tattoos and abuse of psychoactive substances in an autopsy population sample from Greece’, Romanian Journal of Legal Medicine, 26(1), pp. 21-28. Available at: https://doi.org/10.4323/rjlm.2018.21.

Kayiran, M., Ozkul, E., and Gurel, M. (2020). ‘Tattoos: Why do we get? What is our attitude?’, Turk Dermatoloji Dergisi-Turkish Journal of Dermatology, 14(1), pp. 18-22. Available at: https://doi.org/10.4103/TJD.TJD_46_19.

Keagy, C. (2020). ‘A Qualitative Examination of Post-Traumatic Growth in Multiply Body Modified Adults’, Deviant Behavior, 41(5), pp. 562-573. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1080/01639625.2019.1574479.

Kertzman, S., Kagan, A., Hegedish, O., Lapidus, R., and Weizman, A. (2019). ‘Do young women with tattoos have lower self-esteem and body image than their peers without tattoos? A non-verbal repertory grid technique approach’, PLOS ONE, 14(1). Available at: https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0206411.

Klik, E. (2020). ‘Customizing memory: Number tattoos in contemporary Israeli memory work’, Memory Studies, 13(4), pp. 649-661. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1177/1750698017741932.

Kluger, N. (2017). ‘National survey of health in the tattoo industry: Observational study of 448 French tattooists’, International Journal of Occupational Medicine and Environmental Health, 30(1), pp. 111-120. Available at: https://doi.org/10.13075/ijomeh.1896.00634.

Komiya, T., and Iwahira, Y. (2017). ‘A New Local Flap Nipple Reconstruction Technique Using Dermal Bridge and Preoperatively Designed Tattoo’, Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery-Global Open, 5(4). Available at: https://doi.org/10.1097/GOX.0000000000001264.

Lammek, M. (2020). ‘Cellmates versus family—The sense of belonging among tattooed prisoners’, Psychiatria i Psychologia Kliniczna-Journal of Psychiatry and Clinical Psychology, 20(3), pp. 159-163. Available at: https://doi.org/10.15557/PiPK.2020.0020.

Lane, D. (2017). ‘Understanding body modification: A process-based framework’, Sociology Compass, 11(7). Available at: https://doi.org/10.1111/soc4.12495.

Lee, J. (2017). ‘Fashioning women, fastening empire: Domestic dress and savage skin in Mr. Meeson’s Will’, Studies in the Novel, 49(2), p. 189. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1353/sdn.2017.0016.

Levy, M. (2020). ‘In dubio pro CPR? The Controversial Status of `Do Not Resuscitate’ Imprints on the Human Body—A Swiss Innovation’, European Journal of Health Law, 27(2), pp. 125-145. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1163/15718093-BJA10015.

Liebermann, R. (2021). ‘Clothing and body modification in the Hebrew Bible’, Religion Compass, 15(3). Available at: https://doi.org/10.1111/rec3.12389.

López-Naranjo, F., Córdova-Moreno, R., Heyerdahl-Viau, I., and Martínez-Núñez, J. (2023). ‘Evolución histórica y actualidad de los tatuajes’, Fides et Ratio - Revista de Difusión cultural y científica, 25(25), pp. 45-68.

Lynn, C., Puckett, T., Guitar, A., and Roy, N. (2019). ‘Shirts or Skins?: Tattoos as Costly Honest Signals of Fitness and Affiliation among US Intercollegiate Athletes and Other Undergraduates’, Evolutionary Psychological Science, 5(2), pp. 151-165. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40806-018-0174-4.

Maxwell, D., Thomas, J., and Thomas, S. (2020). ‘Cathartic Ink: A Qualitative Examination of Tattoo Motivations for Survivors of Sexual Trauma’, Deviant Behavior, 41(3), pp. 348-365. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1080/01639625.2019.1565524.

Merinov, A., and Vasilyeva, D. (2020). ‘Girls’ tattoos: Their significance for suicidological practice’, Suicidology, 11(1), pp. 153-159. Available at: https://doi.org/10.32878/suiciderus.20-11-01(38)-153-159.

Mironski, J. and Rao, R. (2019). ‘Perception of Tattoos and Piercings in the Service Industry’, Gospodarka Narodowa, 4, pp. 131-147. Available at: https://doi.org/10.33119/GN/113065.

Moher, D., Liberati, A., Tetzlaff, J., Altman, D. G., Altman, D., Antes, G., Atkins, D., Barbour, V., Barrowman, N., Berlin, J. A., Clark, J., Clarke, M., Cook, D., D’Amico, R., Deeks, J. J., Devereaux, P. J., Dickersin, K., Egger, M., Ernst, E., Tugwell, P. (2009). ‘Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement (Chinese edition)’, Journal of Chinese Integrative Medicine, 7(9), pp. 889-896. Available at: https://doi.org/10.3736/JCIM20090918.

Molloy, K. and Wagstaff, D. (2021). ‘Effects of gender, self-rated attractiveness, and mate value on perceptions tattoos’, Personality and Individual Differences, 168. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2020.110382.

Mortensen, K., French, M., and Timming, A. (2019). ‘Are tattoos associated with negative health-related outcomes and risky behaviors?’, International Journal of Dermatology, 58(7), pp. 816-824. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1111/ijd.14372.

Naude, L., Jordaan, J., and Bergh, L. (2019). ‘“My Body is My Journal, and My Tattoos are My Story”: South African Psychology Students’ Reflections on Tattoo Practices’, Current Psychology, 38(1), pp. 177-186. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-017-9603-y.

Ondruschka, B., Ramsthaler, F., and Birngruber, C. G. (2017). ‘Forensic implications of body modifications’, Rechtsmedizin, 27(5), pp. 443-451. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00194-017-0183-9.

Orr, A. (2017). ‘Inked In: The Feminist Politics of Tattooing in Sarah Hall’s The Electric Michelangelo’, Neo-Victorian Studies, 9(2), pp. 97-125.

Osborn, L., and Cohen, P. (2018). ‘Emotional healing with unconventional breast tattoos: The role of temporary tattoos in the recovery process after breast carcinoma and mastectomy’, Clinics in Dermatology, 36(3), pp. 426-429. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clindermatol.2017.11.002.

Rodriguez-Avila, J., Valles-Valles, D., Hernandez-Ayuso, I., Rodriguez-Reyes, A., Morales Canton, V., and Cernichiaro-Espinosa, L. (2020). ‘Conjunctival tattoo with inadvertent ocular globe penetration and vitreous involvement: Clinic-pathological correlation and scanning electron microscopy X-ray microanalysis’, European Journal of Ophthalmology, 30(5). Available at: https://doi.org/10.1177/1120672119850076.

Patterson, M. (2018). ‘Tattoo: Marketplace icon’, Consumption Markets & Culture, 21(6), pp. 582-589. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1080/10253866.2017.1334280.

Ragragio, A., and Paluga, M. (2019). ‘An Ethnography of Pantaron Manobo Tattooing (Pangotoeb): Towards a Heuristic Schema in Understanding Manobo Indigenous Tattoos’, Southeast Asian Studies, 8(2), pp. 259-294. Available at: https://doi.org/10.20495/seas.8.2_259.

Perez-Floriano, L. (2018). ‘Stigma, body symbols and discrimination of consumer and their families’, Cultura y Droga, 25, pp. 67-84. Available at: https://doi.org/10.17151/culdr.2018.23.25.5.

Rahbari, L., Longman, C., and Coene, G. (2019). ‘The female body as the bearer of national identity in Iran: A critical discourse analysis of the representation of women’s bodies in official online outlets’, Gender Place and Culture, 26 (10), pp. 1417-1437. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1080/0966369X.2018.1555147.

Reid-de Jong, V., and Bruce, A. (2020). ‘Mastectomy tattoos: An emerging alternative for reclaiming self’, Nursing Forum, 55(4), pp. 695-702. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1111/nuf.12486.

Santos da Cruz, N., Santos da Cruz, S., Ishigai, D., Santos, K., and Felberg, S. (2017). ‘Conjunctival tattoo: Report on an emerging body modification trend’, Arquivos Brasileiros de Oftalmologia, 80(6), pp. 399-400. Available at: https://doi.org/10.5935/0004-2749.20170098.

Simpson, R., and Pullen, A. (2018). ‘“Cool’ Meanings: Tattoo Artists, Body Work and Organizational “Bodyscape’’, Work Employment and Society, 32(1), pp. 169-185. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1177/0950017017741239.

Sims, J. (2018). ‘“It Represents Me:” Tattooing Mixed-Race Identity’, Sociological Spectrum, 38(4), pp. 243-255. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1080/02732173.2018.1478351.

Tattoo Visibility Status, Egalitarianism, and Personality are Predictors of Sexual Openness Among Women’, Sexuality & Culture-An Interdisciplinary Journal, 24(6), pp. 1935-1956. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12119-020-09729-1.

Smith, M., Starkie, A., Slater, R., and Manley, H. (2021) ‘A life less ordinary: Analysis of the uniquely preserved tattooed dermal remains of an individual from 19th century France’, Archaeological and Anthropological Sciences, 13(3). Available at: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12520-021-01290-8.

Sparkes, A. C., Brighton, J., and Inckle, K. (2021) ‘`I am proud of my back’: An ethnographic study of the motivations and meanings of body modification as identity work among athletes with spinal cord injury’, Qualitative Research in Sport Exercise and Health, 13(3), pp. 407-425. https://doi.org/10.1080/2159676X.2020.1756393.

Steadman, C., Banister, E., and Medway, D. (2019) ‘Ma®king memories: Exploring embodied processes of remembering and forgetting temporal experiences’, Consumption Markets & Culture, 22(3), pp. 209-225. https://doi.org/10.1080/10253866.2018.1474107.

Steckdaub-Muller, I. (2018) ‘“You’ve Got to Do This like a Professional—Not like One of These Scratchers!”. Reconstructing the Professional Self-Understanding of Tattoo Artists’, Cambio-Rivista sulle Trasformazioni Sociali, 8(16), pp. 43-54. https://doi.org/10.13128/cambio-23483.

St-Pierre, C. (2018) ‘Needles and bodies: A microwear analysis of experimental bone tattooing instruments’, Journal of Archaeological Science-Reports, 20, pp. 881-887. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jasrep.2017.10.027.

Strubel, J., and Jones, D. (2017) ‘Painted Bodies: Representing the Self and Reclaiming the Body through Tattoos’, Journal of Popular Culture, 50(6), pp. 1230-1253. https://doi.org/10.1111/jpcu.12626.

Sundberg, K., and Kjellman, U. (2018) ‘The tattoo as a document’, Journal of Documentation, 74(1), pp. 18-35. https://doi.org/10.1108/JD-03-2017-0043.

Tews, M., and Stafford, K. (2019) ‘The Relationship Between Tattoos and Employee Workplace Deviance’, Journal of Hospitality & Tourism Research, 43(7), pp. 1025-1043. https://doi.org/10.1177/1096348019848482.

Tews, M., Stafford, K., and Jolly, P. (2020) ‘An unintended consequence? Examining the relationship between visible tattoos and unwanted sexual attention’, Journal of Management & Organization, 26(2), pp. 152-167. https://doi.org/10.1017/jmo.2019.74.

Thielgen, M., Schade, S., and Rohr, J. (2020) ‘How Criminal Offenders Perceive Police Officers’ Appearance: Effects of Uniforms and Tattoos on Inmates’ Attitudes’, Journal of Forensic Psychology Research and Practice, 20(3), pp. 214-240. https://doi.org/10.1080/24732850.2020.1714408.

Thompson, B. (2020) ‘Academ-Ink: University Faculty Fashion and Its Discontents’, Fashion Theory: The Journal of Dress Body & Culture. https://doi.org/10.1080/1362704X.2020.1764820.

Tierz, S., Navarro, M., Molina, A., Villa, L., Lozano, M., Guerrero, A., Rueda, J., Tierz, S., Navarro, M., Molina, A., Villa, L., Lozano, M., Guerrero, A., and Rueda, J. (2021) ‘Complicaciones y cuidado local de la piel tras la realización de un tatuaje: Revisión sistemática’, Gerokomos, 32(4), pp. 257-262.

Timming, A. (2017) ‘Body art as branded labour: At the intersection of employee selection and relationship marketing’, Human Relations, 70(9), pp. 1041-1063. https://doi.org/10.1177/0018726716681654.

Timming, A., and Perrett, D. (2017) ‘An experimental study of the effects of tattoo genre on perceived trustworthiness: Not all tattoos are created equal’, Journal of Trust Research, 7(2), pp. 115-128. https://doi.org/10.1080/21515581.2017.1289847.

Tomaz, E., and Neves, R. (2019) ‘Body Modifications: Actors and meanings from a web series’, Educação, 44. https://doi.org/10.5902/198464443.5824.

Tranter, B., and Grant, R. (2018) ‘A class act? Social background and body modifications in Australia’, Journal of Sociology, 54(3), pp. 412-428. https://doi.org/10.1177/1440783318755017.

Uzunogullari, S., and Brown, A. (2021) ‘Negotiable bodies: Employer perceptions of visible body modifications’, Current Issues in Tourism, 24(10), pp. 1451-1464. https://doi.org/10.1080/13683500.2020.1797649.

Weiler, S., and Jacobsen, T. (2021) ‘“I’m getting too old for this stuff”: The conceptual structure of tattoo aesthetics*’, Acta Psychologica, 219. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.actpsy.2021.103390.

Witkos, J., and Hartman-Petrycka, M. (2020) ‘Gender Differences in Subjective Pain Perception during and after Tattooing’, International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(24). https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17249466 (Accessed: Date).

Yetisen, A., Moreddu, R., Seifi, S., Jiang, N., Vega, K., Dong, X., Dong, J., Butt, H., Jakobi, M., Elsner, M., and Koch, A. (2019) ‘Dermal Tattoo Biosensors for Colorimetric Metabolite Detection’, Angewandte Chemie-International Edition, 58(31), pp. 10506-10513. https://doi.org/10.1002/anie.201904416.

Zestcott, C., Bean, M., and Stone, J. (2017) ‘Evidence of negative implicit attitudes toward individuals with a tattoo near the face’, Group Processes & Intergroup Relations, 20(2), pp. 186-201. https://doi.org/10.1177/1368430215603459.

38(4), pp.243-255. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1080/02732173.2018.1478351.

Sizer, L. (2020). ‘The Art of Tattoos’, British Journal of Aesthetics, 60(4), pp. 419-433. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1093/aesthj/ayaa012.

Skoda, K., Oswald, F., Brown, K., Hesse, C., and Pedersen, C. (2020). ‘Showing Skin: Tattoo Visibility Status, Egalitarianism, and Personality are Predictors of Sexual Openness Among Women’, Sexuality & Culture-An Interdisciplinary Journal, 24(6), pp. 1935-1956. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12119-020-09729-1.

Smith, M., Starkie, A., Slater, R., and Manley, H. (2021). ‘A life less ordinary: Analysis of the uniquely preserved tattooed dermal remains of an individual from 19th century France’, Archaeological and Anthropological Sciences, 13(3). Available at: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12520-021-01290-8.

Sparkes, A. C., Brighton, J., and Inckle, K. (2021). ‘`I am proud of my back’: An ethnographic study of the motivations and meanings of body modification as identity work among athletes with spinal cord injury’, Qualitative Research in Sport Exercise and Health, 13(3), pp. 407-425. https://doi.org/10.1080/2159676X.2020.1756393.

Steadman, C., Banister, E., and Medway, D. (2019). ‘Ma®king memories: Exploring embodied processes of remembering and forgetting temporal experiences’, Consumption Markets & Culture, 22(3), pp. 209-225. https://doi.org/10.1080/10253866.2018.1474107.

Steckdaub-Muller, I. (2018). ‘“You’ve Got to Do This like a Professional—Not like One of These Scratchers!”. Reconstructing the Professional Self-Understanding of Tattoo Artists’, Cambio-Rivista sulle Trasformazioni Sociali, 8(16), pp. 43-54. https://doi.org/10.13128/cambio-23483.

St-Pierre, C. (2018). ‘Needles and bodies: A microwear analysis of experimental bone tattooing instruments’, Journal of Archaeological Science-Reports, 20, pp. 881-887. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jasrep.2017.10.027.

Strubel, J., and Jones, D. (2017). ‘Painted Bodies: Representing the Self and Reclaiming the Body through Tattoos’, Journal of Popular Culture, 50(6), pp. 1230-1253. https://doi.org/10.1111/jpcu.12626.

Sundberg, K., and Kjellman, U. (2018). ‘The tattoo as a document’, Journal of Documentation, 74(1), pp. 18-35. https://doi.org/10.1108/JD-03-2017-0043.

Tews, M., and Stafford, K. (2019). ‘The Relationship Between Tattoos and Employee Workplace Deviance’, Journal of Hospitality & Tourism Research, 43(7), pp. 1025-1043. https://doi.org/10.1177/1096348019848482.

Tews, M., Stafford, K., and Jolly, P. (2020). ‘An unintended consequence? Examining the relationship between visible tattoos and unwanted sexual attention’, Journal of Management & Organization, 26(2), pp. 152-167. https://doi.org/10.1017/jmo.2019.74.

Thielgen, M., Schade, S., and Rohr, J. (2020). ‘How Criminal Offenders Perceive Police Officers’ Appearance: Effects of Uniforms and Tattoos on Inmates’ Attitudes’, Journal of Forensic Psychology Research and Practice, 20(3), pp. 214-240. https://doi.org/10.1080/24732850.2020.1714408.

Thompson, B. (2020). ‘Academ-Ink: University Faculty Fashion and Its Discontents’, Fashion Theory: The Journal of Dress Body & Culture. https://doi.org/10.1080/1362704X.2020.1764820.

Tierz, S., Navarro, M., Molina, A., Villa, L., Lozano, M., Guerrero, A., Rueda, J., Tierz, S., Navarro, M., Molina, A., Villa, L., Lozano, M., Guerrero, A., and Rueda, J. (2021). ‘Complicaciones y cuidado local de la piel tras la realización de un tatuaje: Revisión sistemática’, Gerokomos, 32(4), pp. 257-262.

Timming, A. (2017) ‘Body art as branded labour: At the intersection of employee selection and relationship marketing’, Human Relations, 70(9), pp. 1041-1063. https://doi.org/10.1177/0018726716681654.

Timming, A., and Perrett, D. (2017) ‘An experimental study of the effects of tattoo genre on perceived trustworthiness: Not all tattoos are created equal’, Journal of Trust Research, 7(2), pp. 115-128. https://doi.org/10.1080/21515581.2017.1289847.

Tomaz, E., and Neves, R. (2019) ‘Body Modifications: Actors and meanings from a web series’, Educação, 44. https://doi.org/10.5902/198464443.5824.

Tranter, B., and Grant, R. (2018) ‘A class act? Social background and body modifications in Australia’, Journal of Sociology, 54(3), pp. 412-428. https://doi.org/10.1177/1440783318755017.

Uzunogullari, S., and Brown, A. (2021) ‘Negotiable bodies: Employer perceptions of visible body modifications’, Current Issues in Tourism, 24(10), pp. 1451-1464. https://doi.org/10.1080/13683500.2020.1797649.

Weiler, S., and Jacobsen, T. (2021) ‘“I’m getting too old for this stuff”: The conceptual structure of tattoo aesthetics*’, Acta Psychologica, 219. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.actpsy.2021.103390.

Witkos, J., and Hartman-Petrycka, M. (2020) ‘Gender Differences in Subjective Pain Perception during and after Tattooing’, International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(24). https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17249466 (Accessed: Date).

Yetisen, A., Moreddu, R., Seifi, S., Jiang, N., Vega, K., Dong, X., Dong, J., Butt, H., Jakobi, M., Elsner, M., and Koch, A. (2019) ‘Dermal Tattoo Biosensors for Colorimetric Metabolite Detection’, Angewandte Chemie-International Edition, 58(31), pp. 10506-10513. https://doi.org/10.1002/anie.201904416.

Zestcott, C., Bean, M., and Stone, J. (2017) ‘Evidence of negative implicit attitudes toward individuals with a tattoo near the face’, Group Processes & Intergroup Relations, 20(2), pp. 186-201. https://doi.org/10.1177/1368430215603459.

de la piel tras la realización de un tatuaje: Revisión sistemática’, Gerokomos, 32(4), pp. 257-262.

Timming, A. (2017). ‘Body art as branded labour: At the intersection of employee selection and relationship marketing’, Human Relations, 70(9), pp. 1041-1063. https://doi.org/10.1177/0018726716681654.

Timming, A., and Perrett, D. (2017). ‘An experimental study of the effects of tattoo genre on perceived trustworthiness: Not all tattoos are created equal’, Journal of Trust Research, 7(2), pp. 115-128. https://doi.org/10.1080/21515581.2017.1289847.

Tomaz, E., and Neves, R. (2019). ‘Body Modifications: Actors and meanings from a web series’, Educação, 44. https://doi.org/10.5902/198464443.5824.

Tranter, B., and Grant, R. (2018). ‘A class act? Social background and body modifications in Australia’, Journal of Sociology, 54(3), pp. 412-428. https://doi.org/10.1177/1440783318755017.

Uzunogullari, S., and Brown, A. (2021). ‘Negotiable bodies: Employer perceptions of visible body modifications’, Current Issues in Tourism, 24(10), pp. 1451-1464. https://doi.org/10.1080/13683500.2020.1797649.

Weiler, S., and Jacobsen, T. (2021). ‘“I’m getting too old for this stuff”: The conceptual structure of tattoo aesthetics*’, Acta Psychologica, 219. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.actpsy.2021.103390.

Witkos, J., and Hartman-Petrycka, M. (2020). ‘Gender Differences in Subjective Pain Perception during and after Tattooing’, International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(24). https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17249466 (Accessed: Date).

Yetisen, A., Moreddu, R., Seifi, S., Jiang, N., Vega, K., Dong, X., Dong, J., Butt, H., Jakobi, M., Elsner, M., and Koch, A. (2019). ‘Dermal Tattoo Biosensors for Colorimetric Metabolite Detection’, Angewandte Chemie-International Edition, 58(31), pp. 10506-10513. https://doi.org/10.1002/anie.201904416.

Zestcott, C., Bean, M., and Stone, J. (2017). ‘Evidence of negative implicit attitudes toward individuals with a tattoo near the face’, Group Processes & Intergroup Relations, 20(2), pp. 186-201. https://doi.org/10.1177/1368430215603459.