Actividades antimicrobianas de especies vegetales recolectadas en la región Noreste de Colombia

Resumen

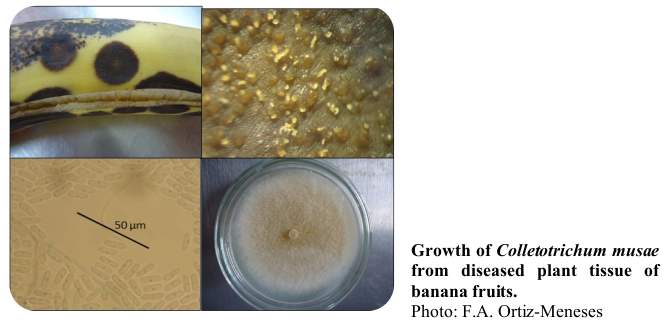

Se han realizado estudios del potencial antimicrobiano de la flora natural, sobre múltiples bacterias (Gram-negativas y Gram-positivas) y hongos. Entre los patógenos de gran importancia se encuentran los del género Colletotrichum, que causan la antracnosis de una gran variedad de plantas. El objetivo de este trabajo fue determinar las actividades antimicrobianas (AAM), de extractos vegetales (EV) y aceites esenciales (AE) de material vegetal recolectado en la región nororiental de Colombia. Para los AE obtenidos de Piper tenue Kunth, Piper eriopodon (Miq.) C. DC., Piper marginatum Jacq., Hyptis suaveolens (L.) Poit, Eriope crassipes Benth. y Lippia origanoides Kunth., se evaluó la aparición de halos de inhibición contra: Staphylococcus aureus, Bacillus cereus, Salmonella typhimurium, Klebsiella spp., Escherichia coli, Aspergillus terreus, Aspergillus fumigatus, Aspergillus niger, Rhizopus spp. y Candida spp. Por otra parte, se estimaron las inhibiciones del crecimiento de Colletotrichum musae Berk. & Curt. y Colletotrichum asianum por EV obtenidos de Ocotea aff. Ocotea caparrapi (Sand.-Groot ex Nates) Dugand, Trattinnickia rhoifolia Willd., Tetragastris panamensis (Engl.) Kuntze y Siparuna guianensis Aubl. Los AE de L. origanoides y E. crassipes, inhibieron el crecimiento de S. typhimurium, A. terreus y Candida spp. Para C. musae: O. aff. O. caparrapi y T. rhoifolia (1,0% p/v), mostraron un porcentaje de inhibición del crecimiento micelial (ICM), y un porcentaje de reducción de la producción de conidios (PRPC) superiores al 85%; T. panamensis y S. guianensis mostraron ICM y PRPC superiores al 71%. Para C. asianum: O. aff. O. caparrapi (1,0% p/v), alcanzó una inhibición superior al 83% (ICM y PRPC), seguido de S. guianensis, T. panamensis y T. rhoifolia. Las AAM tuvieron una alta correlación con el contenido de fenoles. Los AE de L. origanoides y E. crassipes, y el EV de O. aff. O. caparrapi presentaron AAM altas, comparables con las sustancias de control.

Palabras clave

Piperaceae, Lamiaceae, Verbenaceae, Antifungal, Antibacterial

Citas

- Ahad, B., W. Shahri, H. Rasool, Z.A. Reshi, S. Rasool, and T. Hussain. 2021. Medicinal plants and herbal drugs: An Overview. pp. 1-40. In: Aftab, T. and K.R. Hakeem (eds.). Medicinal and aromatic plants. Springer, Cham, Switzerland. Doi: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-58975-2_1

- Almeida, M.C., E.S. Pina, C. Hernandes, S.M. Zingaretti, S.H. Taleb-Contini, F.R.G. Salimena, S.N. Slavov, S.K. Haddad, S.C. França, A.M.S. Pereira, and B.W. Bertoni. 2018. Genetic diversity and chemical variability of Lippia spp. (Verbenaceae). BMC Res. Notes 11, 725. Doi: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13104-018-3839-y

- Balendres, M.A., J. Mendoza, and F. De la Cueva. 2019. Characteristics of Colletotrichum musae PHBN0002 and the susceptibility of popular banana cultivars to postharvest anthracnose. Indian Phytopathol. 73(1), 57-64. Doi: https://doi.org/10.1007/s42360-019-00178-x

- Barbosa, L.C., F. Martins, R. Texeira, M. Polo, and R. Montanari. 2013. Chemical variability and biological activities of volatile oils from H suaveolens (L.) Poit. Agric. Conspec. Sci. 78(1), 1-10. https://acs.agr.hr/acs/index.php/acs/article/view/634/611

- Barreto, H.M., F.C. Fontinele, A.P. Oliveira, D. Arcanjo, B.H.C. Santos, A.P. Abreu, H.D.M. Coutinho, R.A.C. Silva, T.O. Sousa, M.G.F. Medeiros, A.M.G.L. Citó, and J.A.D. Lopes 2014. Phytochemical prospection and modulation of antibiotic activity in vitro by Lippia origanoides H.B.K. in methicillin resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Bio. Med. Res. Int. 2014(1), 305610. Doi: https://doi.org/10.1155/2014/305610

- Butnariu, M. and I. Sarac. 2018. Essential oils from plants. J. Biotechnol. Biomed. Sci. 1(4), 35-43. Doi: https://doi.org/10.14302/issn.2576-6694.jbbs-18-2489

- Can Baer, K.H. and G. Buchbauer. 2015. Handbook of essential oils Science, technology, and applications. Handbook of essential Oils. CRC Press, Boca Raton, FL. Doi: https://doi.org/10.1201/b19393

- Castronovo, L.M., A. Vassallo, A. Mengoni, E. Miceli, P. Bogani, F. Firenzuol, R. Fani, and V. Maggini. 2021. Medicinal plants and their bacterial microbiota: a review on antimicrobial compounds production for plant and human health. Pathogens 10(2), 106. Doi: https://doi.org/10.3390/pathogens10020106

- Cazella, L.N., J. Glamoclija, M. Soković, J.E. Gonçalves, G.A. Linde, N.B. Colauto, and Z.C. Gazim. 2019. Antimicrobial activity of essential oil of Baccharis dracunculifolia DC (Asteraceae) aerial parts at flowering period. Front. Plant Sci. 10, 27. Doi: https://doi.org/10.3389/fpls.2019.00027

- Chassagne, F., T. Samarakoon, G. Porras, J.T. Lyles, M. Dettweiler, L. Marquez, A.M. Salam, S. Shabih, D.R. Farrokhi, and C.L. Quave. 2021. A systematic review of plants with antibacterial activities: a taxonomic and phylogenetic perspective. Front. Pharmacol. 8, 11. Doi: https://doi.org/10.3389/fphar.2020.586548

- Chaurasia, P. and S. Bharati. 2020. Research advances in the fungal world: culture, isolation, identification, classification, characterization, properties and kinetics. Nova Science Publishers.

- Chibane, L.B., P. Degraeve, H. Ferhout, J. Bouajila, and N. Oulahal. 2019. Plant antimicrobial polyphenols as potential natural food preservatives. J. Sci. Food Agric. 99(4), 1457-1474. Doi: https://doi.org/10.1002/jsfa.9357

- Chouhan, S., K. Sharma, and S. Guleria. 2017. Antimicrobial activity of some essential oils present status and future perspectives. Medicines 4(3), 58. Doi: https://doi.org/10.3390/medicines4030058

- Copete-Pertuz, L.S., J. Plácido, E.A. Serna-Galvis, R.A. Torres-Palma, and A. Mora. 2018. Elimination of isoxazolyl-penicillins antibiotics in waters by the ligninolytic native Colombian strain Leptosphaerulina sp. considerations on biodegradation process and antimicrobial activity removal. Sci. Total Environ. 630, 1195-1204. Doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2018.02.244

- Corpogen. 2013. Corporación CorpoGen. In: https://www.corpogen.org; consulted: January, 2013.

- Crouch, J.A., R.J. O’Connell, P. Gan, E.A. Buiate, M.F. Torres, L.A. Beirn, K. Shirasu, and L.J. Vaillancourt. 2014. The genomics of Colletotrichum. pp. 69-102. In: Dean, R., A. Lichens-Park, and C. Kole (eds.). Genomics of plant-associated fungi: monocot pathogens. Springer, Berlin. Doi: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-662-44053-7_3

- Daly, D.C., R.O. Perdiz, P.V.A. Fine, G. Damasco, M.C. Martínez-Habibe, and L. Calvillo-Canadell. 2022. A review of Neotropical Burseraceae. Braz. J. Bot. 45, 103-137. Doi: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40415-021-00765-1

- Da Silva, M.B., Y.F. Figueiredo, D. Silveira, B.G. Brasileiro, M.D.C.P. Batitucci, and C.M. Jamal. 2024. Effect of some medicinal plant crude extracts on growth of Colletotrichum musae, causal agent of banana anthracnose. Rev. Bras. Plantas Med. 22(4), 193-199. Doi: https://doi.org/10.70151/49s58r48

- Da Silva, L.L., H.L.A. Moreno, H.L.N. Correia, M.F. Santana, and M.V. Queiroz. 2020. Colletotrichum: species complexes, lifestyle, and peculiarities of some sources of genetic variability. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 104(5), 1891-1904. Doi: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00253-020-10363-y

- Dastmalchi, K., D. Dorman, M. Kosarb, and R. Hiltunen. 2007. Chemical composition and in vitro antioxidant evaluation of a watersoluble Moldavian balm (Dracocephalum moldavica L.) extract. LWT - Food Sci. Technol. 40, 239-248. Doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lwt.2005.09.019

- De Souza, A.A., B.L.S. Ortíz, R.C.R. Koga, P.F. Sales, D.B. Cunha, A.L.M. Guerra, G.C. Souza, and J.C.T. Carvalho. 2021. Secondary metabolites found among the species Trattinnickia rhoifolia Willd. Molecules 26(24), 7671. Doi: https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules26247661

- García-Gutiérrez, E., M.J. Mayer, P.D. Cotter, and A. Narbad. 2019. Gut microbiota as a source of novel antimicrobials. Gut Microbes. 10(1), 1-21. Doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/19490976.2018.1455790

- ImagenJ. Image Processing and Analysis in Java. In: http://rsbweb.nih.gov; consulted: March, 2023.

- Irazoki, O., S.B. Hernandez, and F. Cava. 2019. Peptidoglycan muropeptides: release, perception, and functions as signaling molecules. Front. Microbiol. 10, 500. Doi: https://doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2019.00500

- Jackson, M. 2014. The mycobacterial cell envelope-lipids. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Med. 4(10), a021105. Doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/cshperspect.a021105

- Jorgensen, J.H. and J.D. Turnidge. 2015. Susceptibility test methods: dilution and disk diffusion methods. In: Jorgensen, J.H., K.C. Carroll, G. Funke, M.A. Pfaller, M.L. Landry, S.S. Richter, and D.W. Warnock (eds.). Manual of clinical microbiology. 11th ed. Wiley Online Library, ASM Press. Doi: https://doi.org/10.1128/9781555817381.ch71

- Khan, M.R. and Z. Haque. 2022. Major diseases of mangos. pp. 191-211. In: Khan, M.R. (ed.). Diseases of fruit and plantation crops and their sustainable management. Nova Science Publishers, New York, NY.

- Kwodaga, J., E.N. Kunedeb, and B. Kongyeli. 2019. Antifungal activity of plant extracts against Colletotrichum gloeosporioides (Penz.) the causative agent of yam anthracnose disease. Arch. Phytopathol. Plant Prot. 52(1-2), 218-233. Doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/03235408.2019.1604303

- Liu, Q., X. Meng, Y. Li, C.N. Zhao, G.Y. Tang, and H.B. Li. 2017. Antibacterial and antifungal activities of spices. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 18(6), 1283. Doi: https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms18061283

- Mahomoodally, M.F., M.Z. Aumeeruddy, L.J. Legoabe, S. Dall'Acqua, and G. Zengin. 2022. Plants' bioactive secondary metabolites in the management of sepsis: recent findings on their mechanism of action. Front. Pharmacol. 13, 1046523. Doi: https://doi.org/10.3389/fphar.2022.1046523

- Masangwa, J.I.G., T.A.S. Aveling, and Q. Kritzinger. 2013. Screening of plant extracts for antifungal activities against Colletotrichum species of common bean (Phaseolus vulgaris L.) and cowpea (Vigna unguiculata (L.) Walp). J. Agric. Sci. 151(4), 482-491. Doi: https://doi.org/10.1017/S0021859612000524

- Mendoza, C.F., A.F. Celis, and M.E.S. Pachón. 2014. Herbicide effects of piper extracts on a seed bank in Fusagasugá (Colombia). Acta Hortic. 1030(9), 77-82. Doi: https://doi.org/10.17660/ActaHortic.2014.1030.9

- Miranda-Cadena, K., C. Marcos-Arias, E. Mateo, J.M. Aguirre-Urizar, G. Quindós, and E. Eraso. 2021. In vitro activities of carvacrol, cinnamaldehyde and thymol against Candida biofilms. Biomed Pharmacother. 143, 112218. Doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biopha.2021.112218

- NCBI, National Center for Biotechnology Information. 2013. Bethesda (MD): National Library of Medicine (US), National Center for Biotechnology Information; – [cited 2013]. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/

- Okonta, E.O., P.F. Onyekere, P.N. Ugwu, H.O. Udodeme, V.O. Chukwube, U.E. Odoh, and C.O. Ezugwu. 2021. Pharmacognostic studies of the leaves of Hyptis suaveolens Linn. (Labiatae) (poit). Pharmacogn J. 13(3), 698-705. Doi: https://doi.org/10.5530/pj.2021.13.89

- Osungunna, M.O. 2020. Screening of medicinal plants for antimicrobial activity: pharmacognosy and microbiological perspectives. J. Microbiol. Biotech. Food Sci. 9(4), 727-735. Doi: https://doi.org/10.15414/jmbfs.2020.9.4.727-735

- Pudziuvelyte, L., M. Stankevicius, A. Maruska, V. Petrikaite, O. Ragazinskiene, G. Draksiene, and J. Bernatoniene. 2017. Chemical composition and anticancer activity of Elsholtzia ciliata essential oils and extracts prepared by different methods. Ind. Crops Prod. 107, 90-96. Doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.indcrop.2017.05.040

- Re, R., N. Pellegrini, A. Proteggente, A. Pannala, M. Yang, and C. RiceEvans. 1999. Antioxidant activity applying an improved ABTS radical cation decolorization assay. Free Radical Biol. Med. 26, 12311237. Doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/s0891-5849(98)00315-3

- Rüdiger, A.L. and V.F. Veiga-Junior. 2013. Chemodiversity of ursane- and oleanane-type triterpenes in amazonian Burseraceae oleoresins. Chem. Biodivers. 10(6), 1142-1153. Doi: https://doi.org/10.1002/cbdv.201200315

- Salleh, W.M.N.H.W. and F. Ahmad. 2017. Phytochemistry and biological activities of the genus Ocotea (Lauraceae): a review on recent research results (2000-2016). J. Appl. Pharm. Sci. 7(5), 204-218. Doi: https://doi.org/10.7324/JAPS.2017.70534

- Sarkic, A. and I. Stappen. 2018. Essential oils and their single compounds in cosmetics a critical review. Cosmetics 5(1), 11. Doi: https://doi.org/10.3390/cosmetics5010011

- Sharifi-Rad, J., A. Sureda, G.C. Tenore, M. Daglia, M. Sharifi-Rad, M. Valussi, R. Tundis, M. Sharifi-Rad, M.R. Loizzo, A.O. Ademiluyi, R. Sharifi-Rad, S.A. Ayatollahi, and M. Iriti 2017. Biological activities of essential oils: from plant chemoecology to traditional healing systems. Molecules 22(1), 70. Doi: https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules22010070

- Statistixm. 2013. 10.0.0.9. Analytical Software. Miller Landing Rd, Tallahassee, FL.

- Tafurt-García, G., L. Jiménez, and A. Calvo. 2015. Antioxidant capacity and total phenol content of Hyptis spp., P. heptaphyllum, T. panamensis, T. rhoifolia, and Ocotea sp. Rev. Colomb. Quim. 44(2), 28-33. Doi: https://doi.org/10.15446/rev.colomb.quim.v44n2.55217

- Tafurt-García, G. and A. Muñoz. 2018. Volatile secondary metabolites in cascarillo (Ocotea caparrapi (Sandino-Groot ex Nates) Dugand - Lauraceae). J. Essent. Oil-Bear. Plants 21(2), 374-387. Doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/0972060X.2018.1465856

- Tafurt-García, G., A. Muñoz-Acevedo, A.M. Calvo, L.F. Jiménez, and W.A. Delgado. 2014. Volatile compounds of analysis of Eriope crassipes, Hyptis conferta, H. dilatata, H. brachiata, H. suaveolens and H. mutabilis (Lamiaceae). Bol. Latinoam. Caribe Plantas Med. Aromat. 13(3), 254-269. https://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=85631010007

- Tafurt-García, G., E. Valenzuela, Y.S. Rodríguez, R.A. Alegría, and E. Stashenko. 2023. Volatile compounds in Piperaceae collected in Arauca-Colombia: Northeastern Region and Colombian-Venezuelan Plains. pp. 26-43. In: da Veiga Jr, V.F., I.A. Ogunwande, and J.L. Martinez (eds.). Essential oils: contributions to the chemical-biological knowledge. CRC Press; Taylor & Francis, Boca Raton, FL.

- Tariq, L., B.A. Bhat, S.S. Hamdani, and R.A. Mir. 2021. Phytochemistry, pharmacology and toxicity of medicinal plants. pp. 217-240. In: Aftab, T. and K.R. Hakeem (eds.). Medicinal and aromatic plants. Springer, Cham, Switzerland. Doi: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-58975-2_8

- Tongnuanchan, P. and S. Benjakul. 2014. Essential oils: extraction, bioactivities, and their uses for food preservation. J. Food Sci. 79(7), 1231-1249. Doi: https://doi.org/10.1111/1750-3841.12492

- Ustáriz, F.J., M.E. Lucena de Ustáriz, F.G. Urbina, D.M. Villamizar, L.B. Rojas, Y.E. Cordero de Rojas, J.E. Ustáriz, L.C. González, and L.M. Araujo. 2020. Composition and antibacterial activity of the Piper Eriopodon (Miq.) C.DC. essential oil from the Venezuelan Andes. Pharmacologyonline 2, 13-22.

- Vaou, N., E. Stavropoulou, C. Voidarou, C. Tsigalou, and E. Bezirtzoglou. 2021. Towards advances in medicinal plant antimicrobial activity: a review study on challenges and future perspectives. Microorganisms 9(10), 2041. Doi: https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms9102041

- Yang, S.K., L.-Y. Low, P. Soo-Xi Yap, K. Yusoff, C.W. Mai, K.S. Lai, and S.-H. Erin Lim. 2018. Plant-derived antimicrobials: insights into mitigation of antimicrobial resistance. Rec. Nat. Prod. 12(4), 295-316. Doi: https://doi.org/10.25135/rnp.41.17.09.058

- Yasmeen, S. and A. Asgar. 2014. Colletotrichum gloeosporioides (Anthracnose). pp. 337-371. In: Bautista-Baños, S. (ed.). Postharvest decay. Academic Press, London. Doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-411552-1.00011-9